Today, the 11th of October 2018, is World Sight Day. Held on the second Thursday of every October it helps to draw awareness to blindness and vision impairment. Statistics show that around 250 people start to lose their vision every day in the UK alone. That’s a grim fact, but the reality of blindness and impaired vision was well known to the Brontës of Haworth.

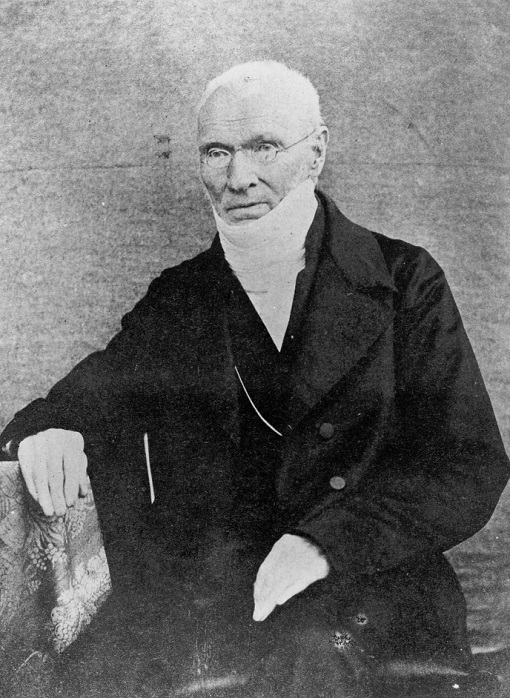

Patrick Brontë lived until he was 84 years old, a grand age for somebody in the nineteenth century, especially in a parish as disease ridden as Haworth. It is testimony to his overall fitness and good health, but as he grew older his eyesight faded rapidly.

He was approaching 43 by the time Anne Brontë, his sixth and final child, was born, and so as the Brontë siblings grew up they had to deal with the fact of their father’s diminishing eyesight. This put pressure on the whole family, but especially the only son Branwell, as if their father’s eyesight failed to the extent where he could no longer do his job it would be expected that he would become the family’s main breadwinner.

The cause of Patrick’s vision problem was cataracts, and the extent of his problem was a newspaper report into a grand concert in Haworth on 20th July 1846. Eighty musicians participated, along with numerous singers, and the Leeds Intelligencer newspaper reported that St. Michael’s and All Angels church was ‘crowded to suffocation’. It also reported that the venerable parish priest Patrick Brontë was also in attendance but it reported, tellingly, that he was ‘now totally blind.’

Patrick was understandably frustrated at his loss of vision. He had to rely increasingly on his assistant curates; he had been a voracious reader, and now his own daughters, and earlier his sister-in-law Elizabeth Branwell, had to read the newspaper to him. In a later letter Charlotte remembered how, ‘Papa’s vision was completely obscured – he could do nothing for himself and sat all day-long in darkness and inertion’.

It could not go on, and so they sought expert, and at the time revolutionary, medical aid. In February 1846, Charlotte consulted an eye surgeon, William Carr, a relation through marriage of Brontë friend Ellen Nussey. Carr advised that Patrick’s cataracts would need to harden before they could be operated on.

In July 1846, not long before the concert mentioned above, Charlotte sought further advice, this time from one of the country’s leading eye surgeons, William James Wilson of Manchester. Emily travelled to Manchester with her, a remarkable fact in itself as by this time she rarely left Haworth and revealing of the loving bond Emily felt for her father. Wilson had founded the Manchester Institution for Curing of the Diseases of the Eye in 1814, but he advised that he could not give a definitive prognosis without seeing Patrick himself.

Charlotte wrote to Ellen explaining how she was going to take her father to the surgeon: ‘Papa must therefore necessarily take a journey to Manchester to consult him – if he judges the cataract ripe we shall remain, if on the contrary he thinks it not sufficiently hardened we shall have to return, and papa must remain in darkness a little while longer.’

On Wednesday 19th August 1846, Charlotte was back in Manchester, this time with Patrick instead of Emily. Dr. Wilson pronounced him a fit subject for surgery, and the operation was performed on August 24th. Charlotte had expected ‘couching’ to be carried out, where the cataract is pushed down allowing some vision to return, but in fact Dr. Wilson cut away the cataracts – without the use of any anaesthetic.

Patrick later wrote in detail what happened during the operation:

‘Belladonna, a virulent poison, prepared from the deadly nightshade, was first applied, twice, in order to expand the pupil. This occasioned very acute pain for only about five seconds. The feeling, under the operation, which lasted 15 minutes, was of a burning nature – but not intolerable – as I have read is generally the case, in surgical operations. My lens was extracted so that cataract can never return in that eye… I was confined on my back a month in a dark room, with bandages over my eyes for the greater part of the time, and had a careful nurse, to attend me both night and day. I was bled with 8 leeches, at one time, and 6, in another, (these caused me little pain) in order to prevent inflammation.’

Poison applied to the eyes, cataracts cut away without anaesthetic, leeches applied to the eyes – all may sound ridiculously primitive to us, but it was cutting edge surgery in more ways than one – and it worked. Patrick regained his eyesight to the extent that he could read again. The month after the operation was a particularly trying one for Charlotte, alone in Manchester with her bandaged father. She must also have been thinking of her own eyesight, which like her father’s had never been strong. Would she too, one day, by lying with bandages over her eyes like this? Would her father ever see again? If not, how would she cope, how would they all cope?

It was at a time when Charlotte was already at a low ebb, as her novel ‘The Professor’ had been rejected by all the publishers she knew of. She could have failed and crumbled, but that wasn’t Charlotte’s way. Her eyesight may have been poor, but her vision was always strong. What happened in that drear apartment at 83 Mount Pleasant Street was described movingly by Charlotte’s friend Elizabeth Gaskell:

‘She had the heart of Robert Bruce within her, and failure upon failure daunted her no more than him. Not only did ‘The Professor’ return again to try his chance among the London publishers, but she began, in this time of care and depressing inquietude – in those grey, weary, uniform streets, where all faces, save that of her kind doctor, were strange and untouched with sunlight to her, – there and then, did the genius begin “Jane Eyre”.’

On World Sight Day let us be thankful for Dr. Wilson, and for countless eye specialists in the health profession in the decades since then. Let us also be thankful for our own sight, that allows us to enjoy the great works of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë.

We should be extremely grateful to not anymore live in such a world but unfortunately hundreds of millions all around the world do & will for many, many years to come.