As we embark upon a rather surreal Mother’s Day here in the United Kingdom, let’s take a break from all illness and viruses and take a look at three very different mothers in the Brontë story.

Let us first look at the actual mother of the Brontës – Maria Brontë, born Maria Branwell in Penzance in April 1883. Maria had a very comfortable life growing up in this picturesque Cornish town: her father was a wealthy merchant and a pillar of society, her brother Benjamin was made Mayor of the town, and she had close friendships with her sisters, especially Elizabeth and Charlotte. As a Branwell she was spared the hardships of life that many Penzance dwellers endured, being reliant upon fishing or tin mining (sometimes with a little piracy and smuggling on the side). She would surely have been seen in the town’s beautiful Assembly Rooms, modelled on those of Bath, and there was also a women’s library for women who, like Maria, could afford it. So why did she give it up all up for a new life of uncertainty amidst the cold northern climes of Yorkshire?

We know that what kept Maria in Yorkshire was love – within months of her arrival at Woodhouse Grove, where she had arrived to help her aunt and uncle run a new Wesleyan school, she had married someone else who had newly arrived in the county – Patrick Brontë. Anne Brontë was surely recalling stories of her mother in her opening to Agnes Grey:

“My mother, who married him against the wishes of her friends, was a squire’s daughter, and a woman of spirit. In vain it was represented to her, that if she became the poor parson’s wife, she must relinquish her carriage and her lady’s-maid, and all the luxuries and elegancies of affluence; which to her were little less than the necessities of life. A carriage and a lady’s-maid were great conveniences; but, thank Heaven, she had feet to carry her, and hands to minister to her own necessities. An elegant house and spacious grounds were not to be despised; but she would rather live in a cottage with Richard Grey than in a palace with any man in the world.”

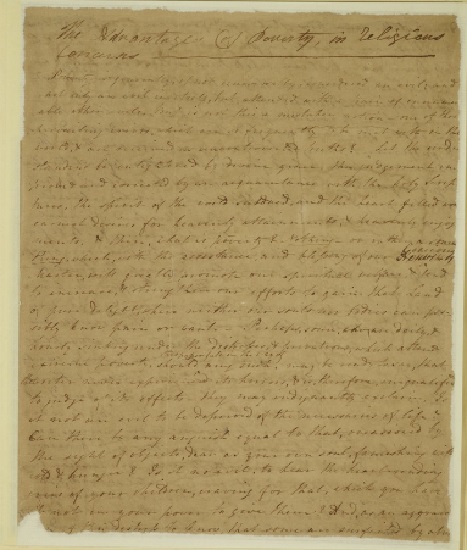

Anne was only one when her mother died, but she would have found a woman whose beliefs were very much aligned with her own. The greatest clue to this was Maria’s essay ‘The Advantages Of Poverty In Religious Concerns’ in which she spells out her own belief in the importance of faith whatever fate has allotted us, and her belief in a caring God. These were themes that are also central to Anne’s work, especially The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall.

Maria Brontë was clearly a remarkable woman in many ways, and a fabulous mother, but it is perhaps strange that Anne, the sibling who could have no knowledge of her mother, is the only Brontë who had mothers in her own novels. Helen, the eponymous tenant of Wildfell Hall, is herself a mother of course, and Agnes Grey’s mother eventually forms a school with her. By contrast, in Wuthering Heights Catherine dies in the moment of becoming a mother, and both Jane Eyre and Lucy Snowe are motherless and being brought up by less than loving members of their extended family. Similarly Shirley Keeldar is a motherless child, as is the real heroine of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Shirley, Caroline Helstone – or is she?

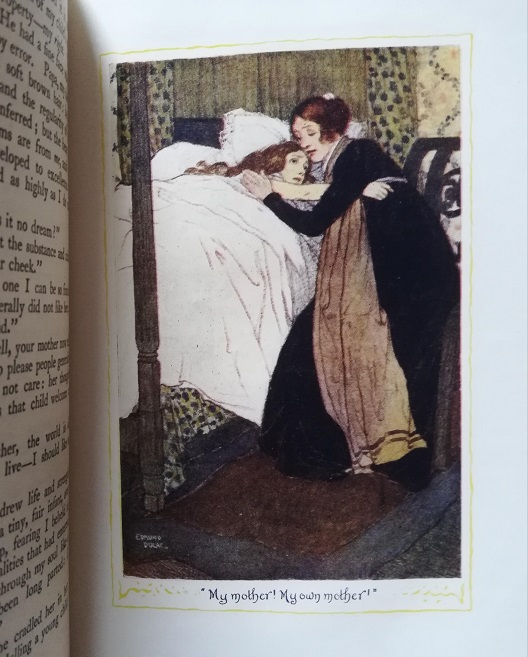

I should perhaps say ‘spoiler alert’ here, for in fact we discover well into the novel that Caroline does have a long-lost mother after all, as Mrs Pryor becomes the only mother figure in Charlotte’s novels. Until that point Mrs Pryor has been merely Shirley’s governess, but with Caroline seemingly on her death bed Mrs Pryor reveals that she was actually born Agnes Grey (a rather striking choice of name by Charlotte) and that she had given Caroline away as a baby. Buoyed by this news, Caroline miraculously recovers and mother and child are reunited at last.

This is a touching, if possibly last minute, device plot from Charlotte. At the time of her commencing the novel, her sister Anne was in good health, but by the time she was writing this scene Anne (and Emily and Branwell before her) had died. I believe that Caroline Helstone is Charlotte’s portrait of Anne Brontë, and that the use of the name Agnes Grey is a tribute from Charlotte to her dead youngest sister. I also believe that Mrs Pryor is Charlotte’s tribute to Aunt Branwell, who had been like a mother to Anne particularly.

Aunt Branwell is often thought of as being stuffy and old fashioned – this was certainly Mary Taylor’s opinion who commented on how Aunt Branwell always wore old fashioned clothing and a plain black silk dress. Ellen Nussey, on the other hand, revealed that the aunt loved nothing more than to talk of her youth in Penzance, and of how she’d been a belle in the town – so what changed?The answer is that Aunt Branwell sacrificed everything for her nieces and nephew – she went without so that they wouldn’t. It is this attribute that Charlotte also gives to Mrs Pryor, and the following passage is Charlotte acknowledging this in print and giving thanks to her aunt, by then also deceased:

“People say you are miserly; and yet you are not, for you give liberally to the poor and to religious societies – though your gifts are conveyed so secretly and quietly that they are known to few except the receivers.”

So we have looked at the Brontë’s real mother, Maria, and at Agnes Pryor, a fictional mother with more than a hint of real life to her. Our third and final mother was all too real, but her circumstances were very shocking.

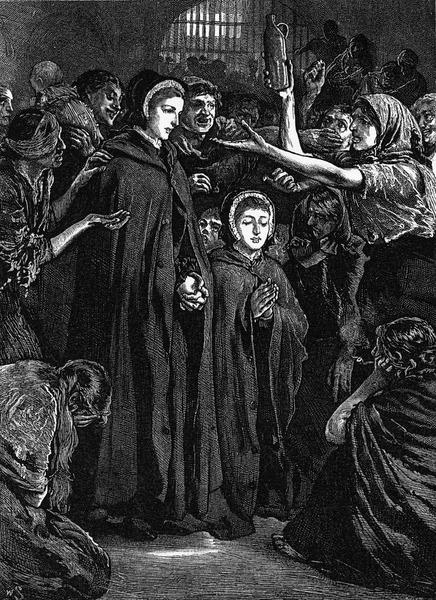

Charlotte Brontë visited London with Anne Brontë in the summer of 1848, but she later visited it on her own on a number of occasions, as the guest of her publisher and friend George Smith. In his memoirs Smith recollected one particularly unique encounter that Charlotte had with a young mother:

“Charlotte Brontë stayed with us several times. The utmost was, of course, done to entertain and please her. We arranged for dinner-parties, at which artistic and literary notabilities, whom she wished to meet, were present. We took her to places which we thought would interest her – The Times office, the General Post Office, the Bank of England, Newgate, Bedlam. At Newgate she rapidly fixed her attention on an individual prisoner. This was a poor girl with an interesting face, and an expression of the deepest misery. She had, I believe, killed her illegitimate child. Miss Brontë walked up to her, took her hand, and began to talk to her. She was, of course, quickly interrupted by the prison warder with the formula, ‘Visitors are not allowed to speak to the prisoners.’”

At Newgate, a brutal jail in Victorian times, Charlotte was brought face to face with a baby killer, a woman who may have been suffering mental illness at the time and who had certainly suffered since. Charlotte didn’t spurn her, but instead reached out and held her hand, whispering words of comfort until stopped – comfort wasn’t allowed in Newgate. This simple act of love and humanity takes us right to the heart of who Charlotte Brontë was.

Charlotte would have been a great mother, but fate took that away from us. We never know what fate has in store, as this year is undoubtedly showing, but all we can do is be the best person that we are capable of, every day. Happy Mother’s Day.

Very interesting Nick thank you for sharing this. I’m still to visit this home