The first draft of Charlotte Brontë’s Villette was finished on this day in 1852, and it would become Charlotte’s final, and many say greatest, completed novel. At these times of self-isolation, and anxiety, reading a great book like Villette can be a source of comfort and entertainment, but writing can be just as rewarding as reading. Many people now find themselves with more time on their hands than they know what to do with, so it’s a good time to do these things we’ve always wanted to – that could include writing a book. If you’re looking for inspiration let’s take a look at just how Charlotte Brontë wrote Villette.

Villette was the third novel of Charlotte’s to be published, after Jane Eyre and Shirley but it was the fourth to be written. Her first completed novel The Professor wasn’t published until after Charlotte’s death, and was rejected by publisher after publisher. In her biographical notice of her sisters Emily and Anne, Charlotte described how the attempt to get published was long, drawn out and ultimately fruitless:

‘These manuscripts were perseveringly obtruded upon various publishers for the space of a year and a half; usually, their fate was an ignominious and abrupt dismissal.’

Here’s Charlotte’s first writing tip. All writers who don’t already have contacts in the industry, even those as great as the Brontës, are rejected by publishers and agents – many time and time again, getting simple one line letters back saying that it isn’t what they’re looking for. It’s easy to be downcast at this, but Charlotte shows the importance of believing in yourself, not giving up, and trying again.

This leads us onto Charlotte’s second writing tip – don’t be afraid to recycle your work, or adapt it into something else. Villette is a unique masterpiece as we follow Lucy Snowe’s life changing journey to Brussels, or Villette as it’s called in the novel – but it clearly borrows from Charlotte’s earlier, unpublished, work The Professor.

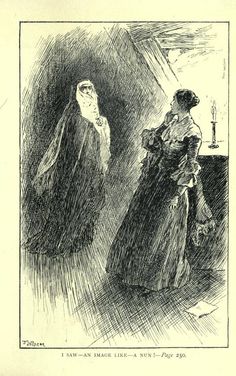

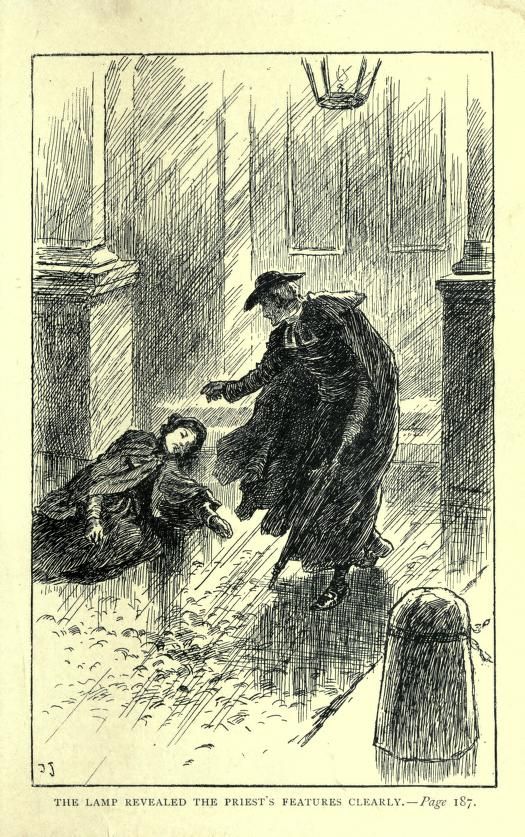

Both are set in Belgium with an English protagonist who arrives at a Brussels school, both deal with a love affair, but the roles are reversed. In her first novel, the main protagonist is the English professor who falls in love with a Swiss pupil, but in Villette the protagonist is the English pupil who falls in love with her Belgian professor. The Professor is well written, with a happy ending, but it occasionally lacks drive and drama. Charlotte took some of the book’s plot, many of its settings and much of its atmosphere and made it into something much darker – there is to be no happy ending in Villette; it is more powerful, more obviously a work of genius, but it owes a lot to the earlier novel and Charlotte’s reworking of it.

The third writing tip from Villette, and indeed all of Charlotte’s novels, is don’t be afraid to draw on real life. It is clear that Paul Emanuel of Villette has much in common with Charlotte’s real life unrequited love Constantin Heger. We also see his wife Clare in the role of Madame Beck, who does all she can to separate Paul and Lucy. This was a very painful episode in Charlotte’s life, and yet she turned that pain into literary gold by setting it down on the page. We all have life experiences, both bad and good, to draw upon, so don’t be afraid to use them in your writing. If you’re worried about people reading your reflections upon them then follow the example of Agnes Grey at the start of Anne Brontë’s first novel: ‘Shielded by my own obscurity, and by the lapse of years, and a few fictitious names, I do not fear to venture.’

Finally, we learn the importance of editing, and in trusting your own gut instinct. In a letter to W. S. Williams in November 1852, she writes: ‘I fear they [readers] must be satisfied with what is offered: my palette affords no brighter tints – were I to attempt to deepen the reds or burnish the yellows I should but botch. Unless I am mistaken, the emotion of the book will be found to be kept throughout in tolerable subjection. As to the name of the heroine – I can hardly express what subtility of thought made me decide upon giving her a cold name; but, at first, I called her “Lucy Snowe” (spelt with an e) which “Snowe” I afterward changed to “Frost”. I rather regretted the change and wished it “Snowe” again: if not too late, I should like the alteration to be made now throughout the manuscript. A cold name she must have… for she has about her an external coldness.’

Charlotte has clearly taken a lot of time in getting the book exactly as she wants it to be. All published authors have to submit to the rigours of being edited, never the most exciting part of being published, but at the end of the day it’s the author’s opinion that must take precedence. At the very last moment, before the book was about to head to the printers, Charlotte changed the name of her heroine from Lucy Frost to Lucy Snowe, and I think we can all agree now that it was a good choice.

So there we have Charlotte’s helpful hints on how to write a book: persevere and don’t let criticism or rejection stop you; don’t be afraid to use previous work or real life in your book; work on your book until you feel it’s just right – and at the end of the day, your opinion is the one that matters.

Of course, Charlotte also had what very few people can be blessed with: genius of the highest order. We may not be able to write a Villette ourselves, but we can still write a book that will entertain ourselves and others. These strange times give us the opportunity to do things we wouldn’t normally have the time to do – so why not make this the year that you finally write the book you’ve always wanted to?

Writing a book, and reading books, can be a great distraction – and that’s a very positive thing at this time when the news seems invariably to be distressing. Distraction, and a celebration of books, is also at the heart of a new project I’ve launched this week – an online literature festival. Real life literature festivals are great fun for participants and audiences, but they’re being cancelled, so my online literature festival will allow you to listen to authors talk about the books and subjects they love, in the comfort of your own home. You can find out more at onlinelitfest.co.uk. Stay safe, stay home, and health and happiness to you and your loved ones.

Inspiring! Thanks for this.

Great advice! Writing is so cathartic, I can understand why all three sisters loved it.

I understand that although I only read the post more than a year after it was released, I felt a bless to have it right by me as a true consolation and inspiration for writing. Of course, I share an extreme admiration for Charlotte Bronte and adore her works, so when I found out this beautiful – though hidden and plain – worldly gem that you wrote, I could not fully express my gratitude to you. Thank you for such a lovely post about Bronte’s writing inspiration.

Thank you very much, and good luck with your writing!