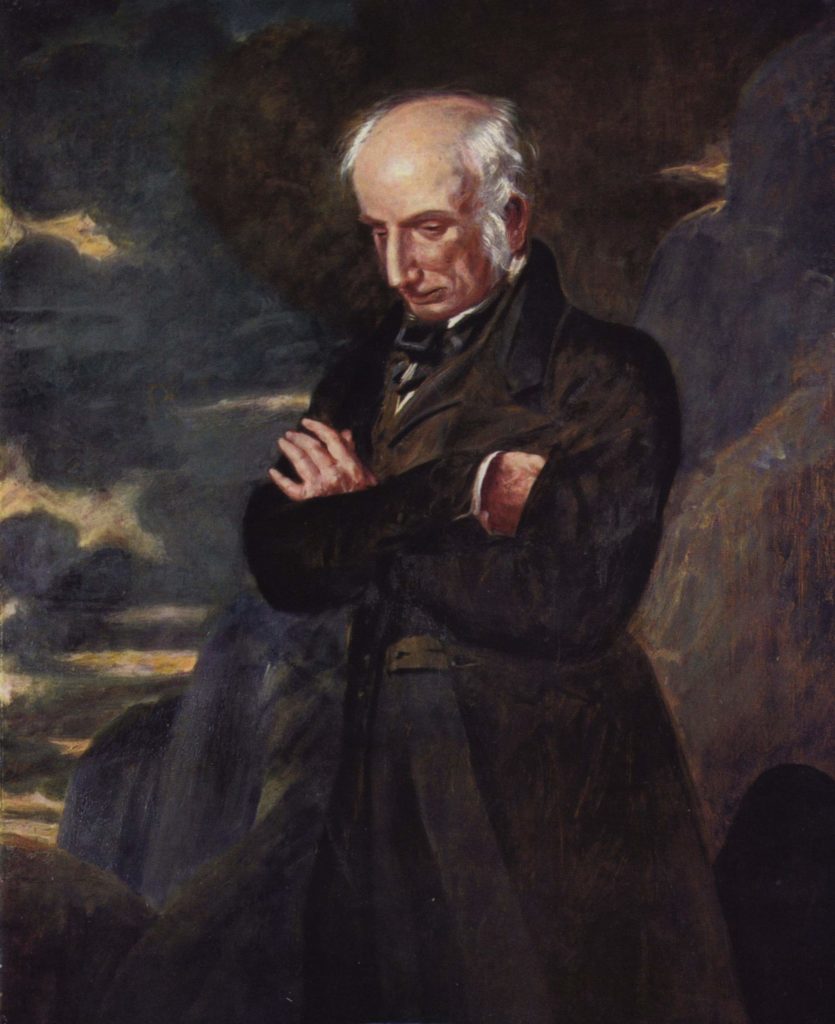

This year, which of course is not as anyone expected or hoped, is the 200th anniversary of the birth of our dear Anne Brontë. An important milestone for this brilliant writer, and she’s certainly in good company for this year also sees milestone anniversaries for two giants of culture. December sees the 250th birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven, and this week saw perhaps the most famous poet of them all reach his quarter of a millennia: William Wordsworth, who was born on April 7th 1770. Wordsworth was a hugely popular and influential poet then and now, and his work was certainly known and loved by the Brontës, as we shall see.

Wordsworth shot rapidly to fame with the publication of Lyrical Ballads in 1798, a collection of verse which he co-authored with his lifelong friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge (of ‘Ancient Mariner’ fame). These youthful poems are beautiful and easily accessible, and rather different to some of the long, complex epic poems he composed in the decades which followed. Among them is a poem that I feel is among Wordsworth’s greatest works. ‘We Are Seven’ tells of a young maid who will always remember her siblings, even though they are dead and buried. It is a poem of sibling love and of infant mortality, and it always reminds me of the early losses that the Brontës and other families suffered.

Lyrical Ballads is often credited with starting a whole new poetic movement: Romanticism. Future poetic greats such as Byron, Shelley and Keats certainly had a lot to thank William Wordsworth for, and he became the father figure of the romantic poets. Others thankful for his work were a certain family of Haworth Parsonage, and we get evidence of this in a letter dated 4th July 1834 from Charlotte Brontë to her former school friend Ellen Nussey, in which she advises Ellen on what she should be reading:

“If you like poetry let it be first rate, Milton, Shakespeare, Thomson, Goldsmith, Pope (if you will although I don’t admire him), Scott, Byron, Campbell, Wordsworth and Southey… Scott’s sweet, wild romantic Poetry can do you no harm nor can Wordsworth’s nor Campbell’s nor Southey’s, the greatest part at least of his, some is certainly exceptionable.”

In light of Southey’s infamous letter later sent to Charlotte, saying that writing could never be the business of women, it’s good to see that Charlotte passed judgement on him too. For Wordsworth though she had only good words, and one member of her family was particularly fulsome in his praise of the great poet: her brother Branwell.

Branwell hero worshipped William Wordsworth, a literary obsession that was brought to the surface when he sent Wordsworth a letter in January 1837, alongside the opening to a long poem. I reproduce it here in full, because it’s a fascinating letter that gives us insight into the huge esteem with which Branwell, and his sisters, held Wordsworth, and also into the mind of Branwell at the height of his positivity:

”Sir, I most earnestly entreat you to read and pass your judgment upon what I have sent you, because from the day of my birth, to this the nineteenth year of my life, I have lived among secluded hills, where I could neither know what I was, or what I could do. I read for the same reason that I ate or drank – because it was a real craving of nature. I wrote on the same principle as I spoke – out of the impulse and feelings of the mind; nor could I help it, for what came, came out, and there was the end of it. For as to self-conceit, that could not receive food from flattery, since to this hour not half-a-dozen people in the world know that I have ever penned a line.

But a change has taken place now, sir; and I am arrived at an age wherein I must do something for myself: the powers I possess must be exercised to a definite end, and as I don’t know them myself I must ask of others what they are worth. Yet there is not one here to tell me; and still, if they are worthless, time will henceforth be too precious to be wasted on them.

Do pardon me, sir, that I have ventured to come before one whose works I have most loved in our literature, and who most has been with me a divinity of the mind, laying before him one of my writings, and asking of him a judgment of its contents. I must come before some one from whose sentence there is no appeal; and such a one is he who has developed the theory of poetry as well as its practice, and both in such a way as to claim a place in the memory of a thousand years to come.

My aim, sir, is to push out into the open world, and for this I trust not poetry alone – that might launch the vessel, but could not bear her on; sensible and scientific prose, bold and vigorous efforts in my walk in life, would give a further title to the notice of the world; and then, again, poetry ought to brighten and crown that name with glory; but nothing of all this can be ever begun without means, and as I don’t possess these, I must in every shape strive to gain them. Surely, in this day, when there is not a writing poet worth a sixpence, the field must be open, if a better man can step forward.

What I send you is the Prefatory Scene of a much longer subject, in which I have striven to develop strong passions and weak principles struggling with a high imagination and acute feelings, till, as youth hardens towards old age, evil deeds and short enjoyments end in mental misery and bodily ruin. Now, to send you the whole of this would be a mock upon your patience; what you see, does not even pretend to be more than the description of an imaginative child. But read it, sir; and, as you would hold a light to one in utter darkness – as you value your own kind-heartedness – return me an answer, if but one word, telling me whether I should write on, or write no more. Forgive undue warmth, because my feelings in this matter cannot be cool; and believe me, sir, with deep respect, Your really humble servant, P. B. Brontë”

It’s easy to look upon this letter as a trifle embarrassing, but it shows the great confidence that Branwell had at this time, in himself and his writing, and he was certainly a man who would take action rather than waiting for whatever fate had in store. He wanted a critique of his poetry, so he had no hesitation in writing to the greatest poet of all. Reply came there none, but the fact remains that William Wordsworth kept the letter, so it must have interested him in some way, or perhaps he felt some affinity with Branwell even though he’d claimed that there wasn’t a writing poet worth sixpence.

Branwell never heard back from Wordsworth, but he had better luck with the family of Wordsworth’s great associate Samuel Taylor Coleridge, striking up a correspondence with his eldest son Hartley Coleridge, and visiting him at Nab Cottage at Ambleside. Hartley was impressed by Branwell’s writing, praising his ‘masterly versification.’

Nab Cottage was also in close proximity to Grasmere, the Lake District location that William Wordsworth has made forever famous. In 1840, Branwell too was in the Lake District, serving as governor to the Postlethwaite family of Broughton-in-Furness. We know he visited Hartley Coleridge, could he have visited his hero William Wordsworth too? Branwell’s friend Francis Leyland believed so.

Wordsworth loved nature, enjoying nothing so much as walking the hills and fells of the Lake District, particularly when in company with his beloved sister Dorothy. There can be little doubt then that Emily and Anne Brontë, who loved to walk the moors together, would have felt a strong affinity with him. His pastoral poems took nature poetry to new heights, and we can see the effect they had on Charlotte Brontë in an 1850 letter to Margaret Wooler in which she details her own journey to the ‘Lake-Country’ to visit the wealthy Kay Shuttleworth family:

“Sir James Kay Shuttleworth is residing near Windermere at a house called ‘the Briery’ – and it was there I was staying for a little time in August. He very kindly shewed me the scenery, as it can be seen from a carriage, and I discerned that the ‘Lake-Country’ is a glorious region – of which I had only seen the similitude in dreams – waking or sleeping – but, my dear Miss Wooler, I only half enjoyed it – because I was only half at my ease.

Decidedly, I find it does not agree with me to prosecute the search for the picturesque in a carriage. A waggon, a spring-cart, even a post-chaise might do – but the carriage upsets everything. I longed to slip out unseen, and to run away by myself in amongst the hills and dales. Erratic and vagrant instincts tormented me, and these I was obliged to control, or rather suppress, for fear of growing in any degree enthusiastic, and thus drawing attention to the ‘lioness’, the authoress – the she-artist.”

William Wordsworth could certainly have sympathised with this dilemma, he became a much sought out public figure at his home at Rydal Mount where he spent the last 37 years of his life (that’s it at the top of this post), but really he prized solitude and the company of close friends. He was finally made poet laureate in 1843, after which he became the only poet laureate not to write a single line of official verse. Wordsworth had put down his quill forever, but he’d already left a stunning legacy which will always tower over the world of verse. As I type this, the sublime Egmont Overture is playing on the radio – and we return again to those other 2020 milestone holders Beethoven and Anne Brontë, along with Wordsworth they make a brilliant trio full of remarkable genius and the courage to set their own agendas rather than following conventions.

From Wordsworth, Beethoven and Anne we can learn a message that’s of vital importance today – we may be solitary at times, but our minds are free to roam where we please, and the endless bounties of nature will always be available to us. Stay healthy, stay indoors, and if you celebrate it may I wish you a Happy Easter.

Wonderful post! I never knew that Branwell wrote to Wordsworth. I wonder why Wordworth kept the letter….

Happy Easter, Nick!

Thanks Ann!

Thank you Nick, another brilliant read.

I would think that Keats would have a lot more in common with Brontë poetry than either Wordsworth or Coleridge. Is there any written evidence that they perused Keats? We know they were allowed to read Byron, but to what effect I do not know.

A brill read Nick. Bran faced enormous challenges, no silver spoon. Perhaps he was hoping Wordsworth would recognise his name, since he makes no reference to fact, that Wordsworth and Wilberforce corresponded and exchanged poems and sonnets with Patrick Bronte and, John Landseer. Wilberforce sponsored Patrick’s 3rd year at Cambridge. He and Wordsworth visited John Landseer’ home when in London. Only just discovered this enchanting legacy of family association. Hope is of value to you. Best wishes, Jam

I should mention; Benjamin Heydon, who made Wordsworth’s portrait above, was a pal of John Landseer, and tutored Edwin.