As the UK prepares to enter the next stage of its long walk to freedom and safety, many will reflect on the lessons they’ve learnt during this strange, often unsettling and sometimes tragic year. Many will have learnt what’s truly important to them: the people they love, those who have been there for them through the ups and downs of 2020. That’s why the year to come could see a surge in engagements, and a raft of weddings, which will be wonderful for all concerned. Rather fittingly today marks the 167th anniversary of the date on which Charlotte Brontë accepted the proposal of Arthur Bell Nicholls; as we shall see in this post, it was far from her first proposal of marriage.

As far as we can tell, and there may have been other proposals that have been lost to posterity, Charlotte’s first proposal of marriage came on 1st March 1839 from the Reverend Henry Nussey. This looked a promising match at first – Henry was elder brother to Charlotte’s best friend Ellen Nussey, and Charlotte knew and liked him. There was one crucial element missing however: romance.

Henry was looking for a wife, but he didn’t really care who that wife was. In fact, he wrote proposing marriage to Charlotte just a week after he had received a refusal from a proposal he had made to Margaret Lutwidge (whose nephew Charles later became famous as Wonderland creator Lewis Carroll). Ellen was obviously aware of Henry’s plans and had asked Charlotte about them, for on 12th March Charlotte wrote:

‘You ask me dear Ellen whether I have received a letter from Henry. I have about a week since, the contents I confess did a little surprise me, but I kept them to myself, and unless you had questioned me on the subject I would never have adverted to it. Henry says he is comfortably settled in Sussex, that his health is much improved & that it is his intention to take pupils after Easter – he then intimates that in due time he shall want a Wife to take care of his pupils and frankly asks me to be that Wife… I asked myself two questions – ‘Do I love Henry Nussey as much as a woman ought to love her husband? Am I the person best qualified to make him happy?’ Alas Ellen my Conscience answered no to both these questions. I felt that though I esteemed Henry, though I had a kindly leaning towards him because he is an amiable well-disposed man, yet I had not, and never could have that intense attachment which would make me willing to die for him – and if ever I marry it must be in that light of adoration that I will regard my Husband. Ten to one I shall never have the chance again but n’importe. Moreover, I was aware that Henry knew so little of me he could hardly be conscious to whom he was writing – why it would startle him to see me in my natural home-character, he would think me a wild, romantic enthusiast indeed. I could not sit all day long making a grave face before my husband – I would laugh and satirize and say whatever came into my head first – and if he were a clever man & loved me the whole world weighed in the balance against his smallest wish should be light as air. Could I, knowing my mind to be such as that, could I consciously say that I would take a grave quiet young man like Henry? No it would have been deceiving him.’

This grave young man was in search of a wife to help him in his ministerial duties, and whilst vicar of Hathersage he married Emily Prescott. Hathersage is the Morton of Jane Eyre and Henry Nussey undoubtedly inspired St. John Rivers. Alas, Henry could not defeat the illness Charlotte alluded to in her letter, and he died in an asylum in 1860.

Charlotte Brontë did not have to wait long for her next proposal of marriage, and once more it came out of the blue. On 4th August 1839, she was again writing to Ellen:

‘I have an odd circumstance to relate to you, prepare for a hearty laugh – the other day Mr Hodgson, Papa’s former curate, now a Vicar, came over to spend the day with us, bringing with him his own curate. The latter Gentleman by name Mr Price is a young Irish clergyman fresh from Dublin University – it was the first time we had any of us seen him, but however after the manner of his Countrymen he soon made himself at home. His character quickly appeared in his conversation – witty, lively, ardent, clever too – but deficient in the dignity & discretion of an Englishman. At home you know Ellen I talk with ease and am never shy – never weighed down & oppressed by that miserable mauvais honte which torments and constrains me elsewhere, so I conversed with this Irishman & laughed at his jests – & though I saw faults in his character excused them because of the amusement his originality afforded. I cooled a little indeed & drew in towards the latter part of the evening, because he began to season his conversation with something of Hibernian flattery which I did not quite relish, however they went away and no more was thought about them.

A few days after I got a letter the direction of which puzzled me, it being in a hand I was not accustomed to see. Evidently it was neither from you nor Mary Taylor, my only Correspondents. Having opened & read it, it proved to be a declaration of attachment & proposal of Matrimony expressed in the ardent language of the sapient young Irishman!

Well thought I – I’ve heard of love at first sight but this beats all… I hope you are laughing heartily… I’m certainly doomed to be an old maid Ellen – I can’t expect another chance – never mind I made up my mind to that fate ever since I was twelve years old.’

It was Reverend David Pryce (not ‘Price’ as Charlotte spelled it) who was rebuffed in late 1839; he died suddenly less than a year later aged 28. Charlotte had resigned herself to receiving no further proposals, but she was quite wrong to do so.

In April 1851 it seems that Charlotte received her third proposal of marriage. By this time she had lost her siblings, and had also found great success as the writer Currer Bell. This time she had enchanted one of the management team at her publisher Smith, Elder & Co named Joe Taylor. It was Taylor who was sent to Haworth to collect the completed manuscript of Shirley from Charlotte in September 1849, and they met on a number of prior and subsequent occasions. Joe, like others before him, clearly fell head over heels for Charlotte, but Charlotte loved handsome men, and he didn’t fit the bill – as we can see from her letter to Ellen of 5th December 1849:

‘Mr Taylor – the little man – has again shewn his parts. Of him I have not yet come to a clear decision: abilities he has for he rules the firm – he keeps 40 young men under strict control by his iron will. His young superior [George Smith] likes him which, to speak the truth, is more than I do at present. In fact, I suspect he is of the Helstone order of men [the Reverend Helstone appears in Shirley] – rigid, despotic and self-willed. He tries to be very kind and even to express sympathy sometimes, and he does not manage it. He has a determined, dreadful nose in the middle of his face which when poked into my countenance cuts into my soul like iron. Still, he is horribly intelligent.’

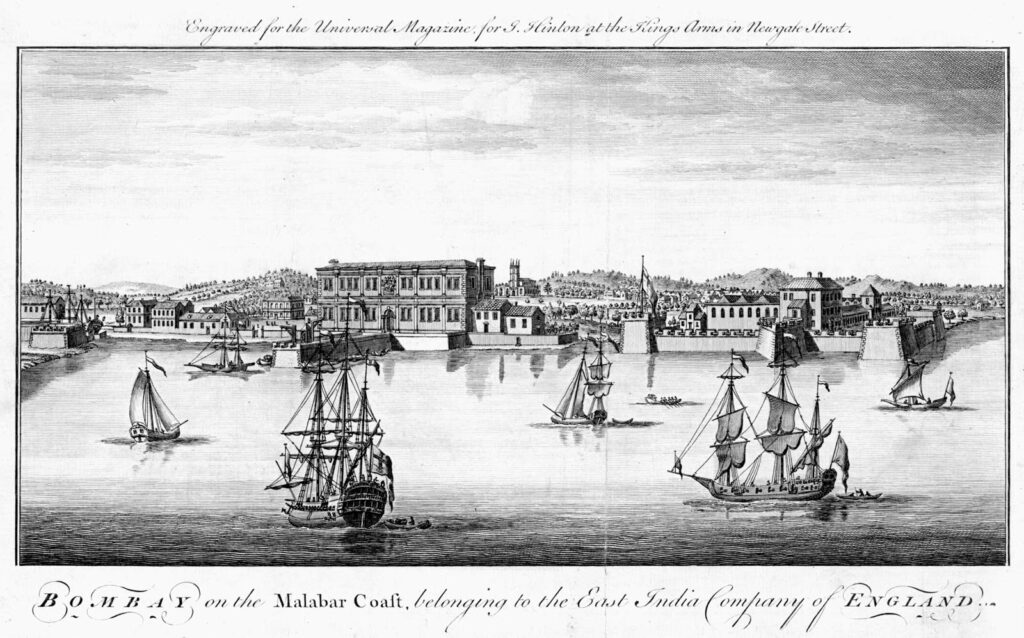

In the spring of 1851 Joe Taylor left England for India to expand the Smith publishing business there. He visited Charlotte before leaving on 9th April, and it is thought that he proposed marriage to her on this occasion. Charlotte met his proposal with anger, and he sailed away to Mumbai, where he died in 1874.

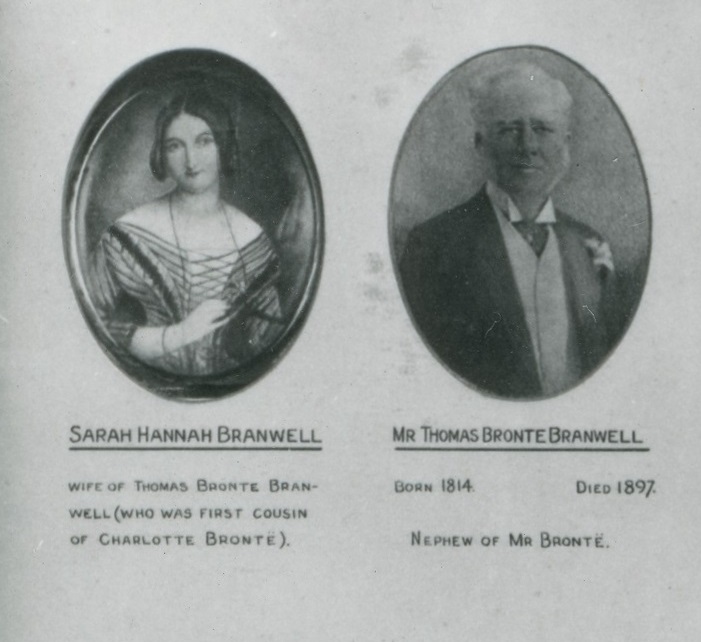

Once again marriage proposals followed hot on the heels of each other, and the next came via a visitor from the Brontë motherland – Penzance in Cornwall. Thomas Brontë Branwell arrived at Haworth Parsonage in September 1851, and remained there for a week. He was Charlotte’s cousin, the son of the woman after whom she had been named: Charlotte Branwell, younger sister of Maria. Why did Thomas make that 400 mile journey?

The most likely explanation seems to me that he intended to propose to Charlotte; after all his own mother and father, Charlotte and Joseph Branwell, were themselves cousins. Thomas too was rebuffed; he later married Sarah Hannah Jones. Thomas had failed to marry Charlotte Brontë, but his son did – in a way. In 1897 Arthur Milton Cooper Branwell married his cousin – one Charlotte Brontë Jones.

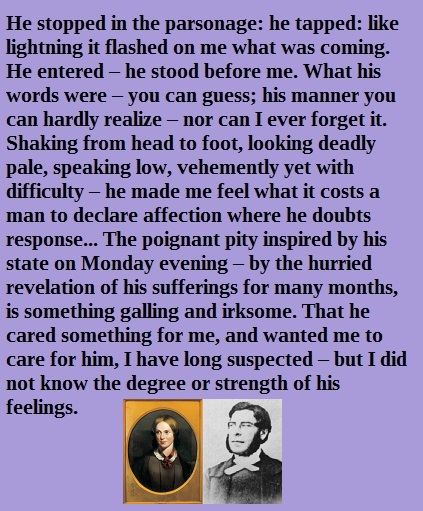

There is no doubt about Charlotte’s next proposal, in December 1852, and we all know how it turned out. Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father’s assistant curate, proposed twice. His first proposal was rather less than well received as we see in this letter to Ellen:

A rejected and dejected Arthur pledged to leave Haworth forever. In his final appearance at Haworth’s church he had to be led shaking from the pulpit, unable to speak, and Charlotte later found him ‘sobbing as women never sob.’ Arthur, however, continued to write to Charlotte and returned in triumph on this day in 1854 when the woman he loved accepted his second proposal.

Charlotte Brontë was not destined to be an ‘old maid’ after all, and love had won the day. I propose that you join me next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.