Vegetarianism and veganism are becoming increasingly popular. Whilst these terms were unheard of in the first half of the nineteenth century, there surely were people who followed these diets. In today’s post we’re going to look at whether the Brontës really did have a meat free diet, something that was first suggested in this passage from Elizabeth Gaskell’s Life Of Charlotte Brontë:

‘But there never were such good children. I used to think them spiritless, they were so different to any children I had ever seen. In part, I set it down to a fancy Mr. Brontë had of not letting them have flesh-meat to eat. It was from no wish for saving, for there was plenty and even waste in the house, with young servants and no mistress to see after them; but he thought that children should be brought up simply and hardily; so they had nothing but potatoes for their dinner.’

There were a number of passages in the first edition of Gaskell’s book which showed Patrick in a less than favourable light, but it was this one in particular that he took umbrage with, as we see in a letter published by the ‘Daily News’ on this week in 1857, just five months after the biography of Charlotte Brontë was published. On 21st August 1857 the newspaper published a response from William Dearden, the indefatigable defender of Patrick Brontë who we’ve encountered in a previous post, in which he denied many of the books claims:

‘With regard to the statement that Mr. Brontë, in his desire to bring up his children simply and hardily, refused to permit them to eat flesh meat, he asserts that Nancy Garrs alleges that the children had meat daily, and as much other food as they chose. The only article from which they were restrained was butter, but its want was compensated for by what is known in Yorkshire as “spice-cake,” a description of bread which is the staple food at Christmas for all meals but dinner.’

The article also includes a quote attributed directly to Patrick himself:

‘I did not know that I had an enemy in the world, much less one who would traduce me before my death. Everything in that book which relates to my conduct to my family is either false or distorted. I never did commit such acts as are ascribed to me. I stated this in a letter which I sent to Mrs Gaskell, requesting her at the same time to cancel the false statements made about me in her next edition of her book. To this I received no answer than that Mrs Gaskell was unwell, and unable to write.’

For corroboration of Dearden’s words we can turn to an interview with Nancy Garrs herself to the Leeds Mercury and which was published in 1893:

‘The assertion that Mr Brontë would not allow his children butter, and that they had little animal food provided, Nancy also stated to be false. “Why,” said she, laughing derisively, “I was the cook, and if at any time they had no butter on their bread it was because there were good currants in it. Meat the children had every day of their lives, cooked on that very meat-jack you see above your heads, gentlemen. That was Mr Brontë’s jack, and after his death it was sent to me. Aye,” continued she, with a look which showed she was thinking of the chequered past in her youthful home, “Mr Brontë was one the kindest husbands I ever knew, except my own, and an Irishman, you will know Mr Brontë was.’

It seems that Patrick Brontë had indeed an enemy, although one he may well have forgotten, and that it was they who had fed false tales to Elizabeth Gaskell who then took them in good faith – the passages were later removed from later editions of the biography. The informant in question was a Martha Heaton, nee Wright, who had worked as a nursemaid in the parsonage during the final illness of Patrick’s wife Maria. She was dismissed soon after the arrival from Cornwall of Elizabeth ‘Aunt’ Branwell in Haworth, and may have held a grudge against both Patrick and Elizabeth.

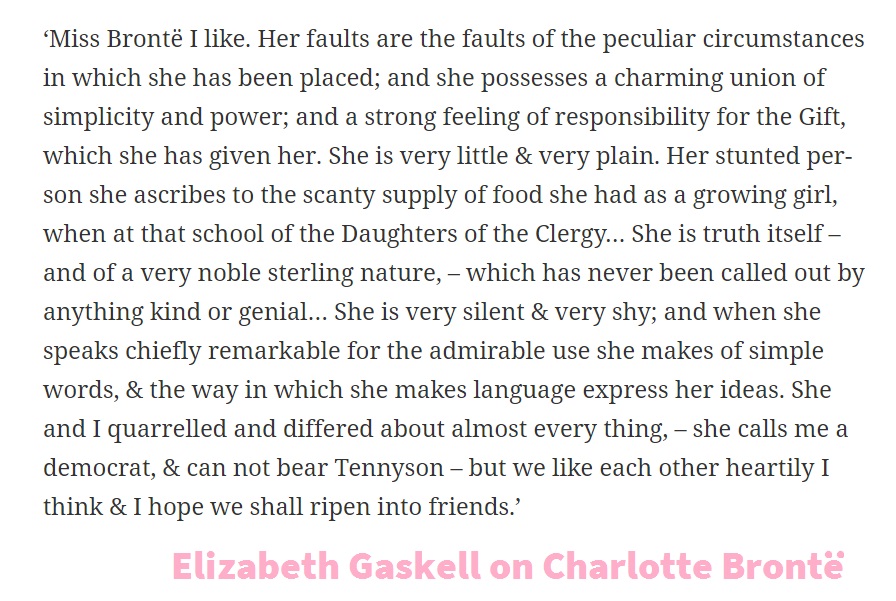

A letter from Elizabeth Gaskell to her friend Charlotte Froude in August 1850, shortly after her first encounter with Charlotte Brontë, reveals that Charlotte stated that she had endured a poor diet not at home in Haworth Parsonage but at school in Cowan Bridge:

This recollection did not make its way into Gaskell’s biography but one that did is a recollection by Mary Taylor of the Charlotte Brontë she had known at Roe Head school:

‘She said she had never played, and could not play. We made her try, but soon found that she could not see the ball, so we put her out. She took all our proceedings with pliable indifference, and always seemed to need a previous resolution to say “No” to anything. She used to go and stand under the trees in the play-ground, and say it was pleasanter. She endeavoured to explain this, pointing out the shadows, the peeps of sky, &c. We understood but little of it. She said that at Cowan Bridge she used to stand in the burn, on a stone, to watch the water flow by. I told her she should have gone fishing; she said she never wanted. She always showed physical feebleness in everything. She ate no animal food at school.’

A typically blunt assessment from Mary, and it seems to point to Charlotte avoiding meat at this point in her life because of a lifestyle choice. Nevertheless we know that Charlotte did resume eating meat again; the reason why was outlined in Ellen Nussey’s memoir, ‘Reminiscences of Charlotte Bronte’:

‘Her appetite was of the smallest; for years she had not tasted animal food; she had the greatest dislike to it; she always had something specially provided for her at our midday repast. Towards the close of the first half-year she was induced to take, by little and little, meat gravy with vegetable, and in the second half-year she commenced taking a very small portion of animal food daily. She then grew a little bit plumper, looked younger and more animated, though she was never what is called lively at this period.’

If Charlotte had had access to the information we have today on nutritional content, and with today’s dietary supplements, it seems possible, even probable, that Charlotte Brontë would have remained vegetarian.

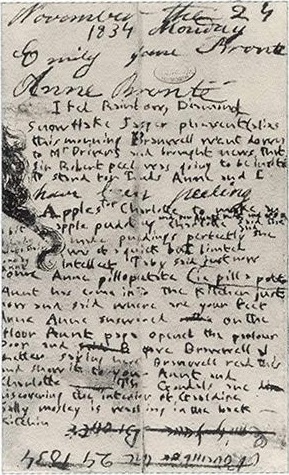

The greatest proof that the Brontës did eat meat comes from the Brontës themselves. The 1834 diary paper composed jointly by Emily and Anne Brontë provides a snapshot of a day in the life of the two teenage sisters, and it also reveals what they were having for dinner:

‘It is past Twelve o’clock Anne and I have not tided ourselves, done our bed work done our lessons and we want to go out to play. We are going to have for dinner boiled beef, turnips, potato’s and apple pudding, the kitchin is in a very untidy state.’

All in all that sounds like a fine, balanced meal, and certainly disproves Martha Wright’s tale that the Brontë children were given spartan dinners. Whatever you are having for your Sunday lunch I hope you enjoy it, and I hope to see you here next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Great post Nick

It seems absurd the things that Elizabeth Gaskell made so many false statements regarding Mr. Bronte. So unfortunate, and he took it with a great deal of dignity too. Great article!