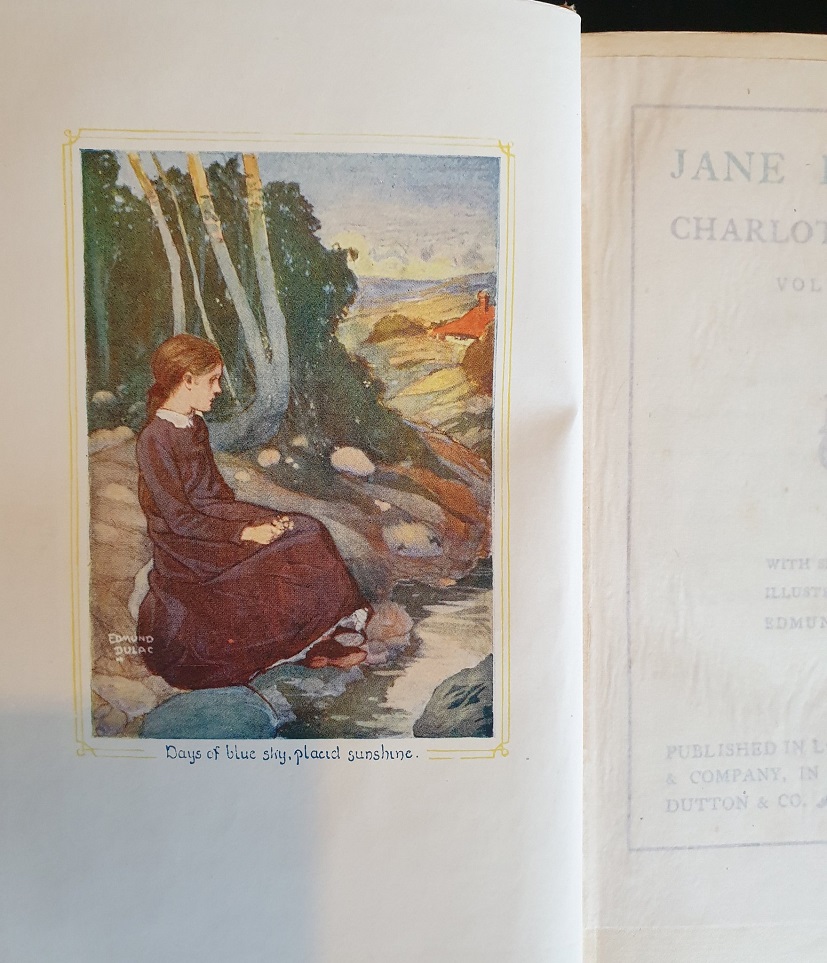

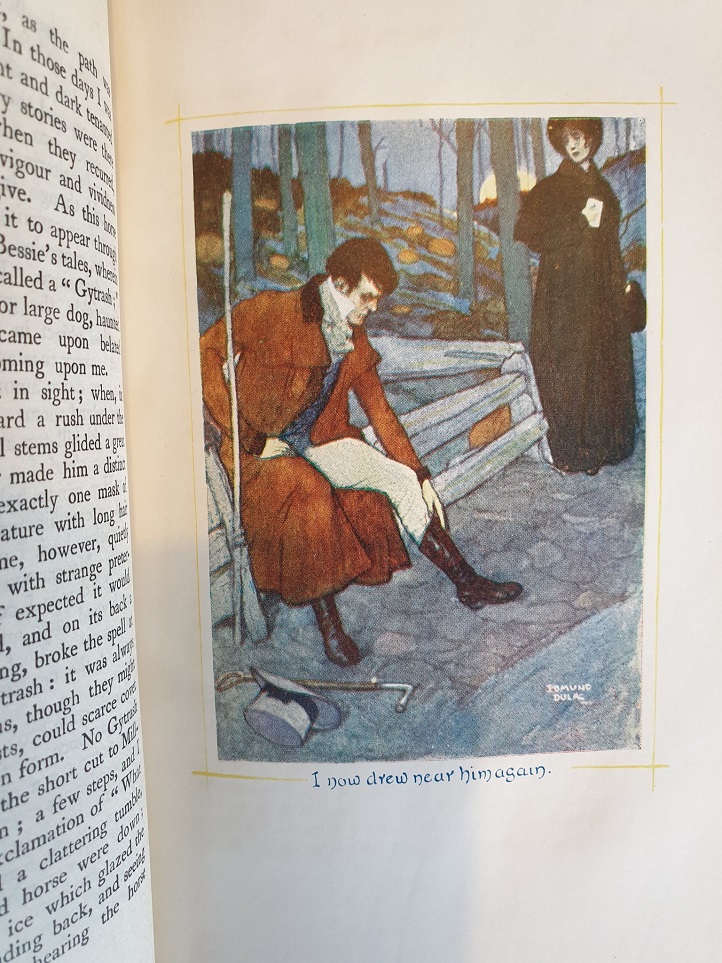

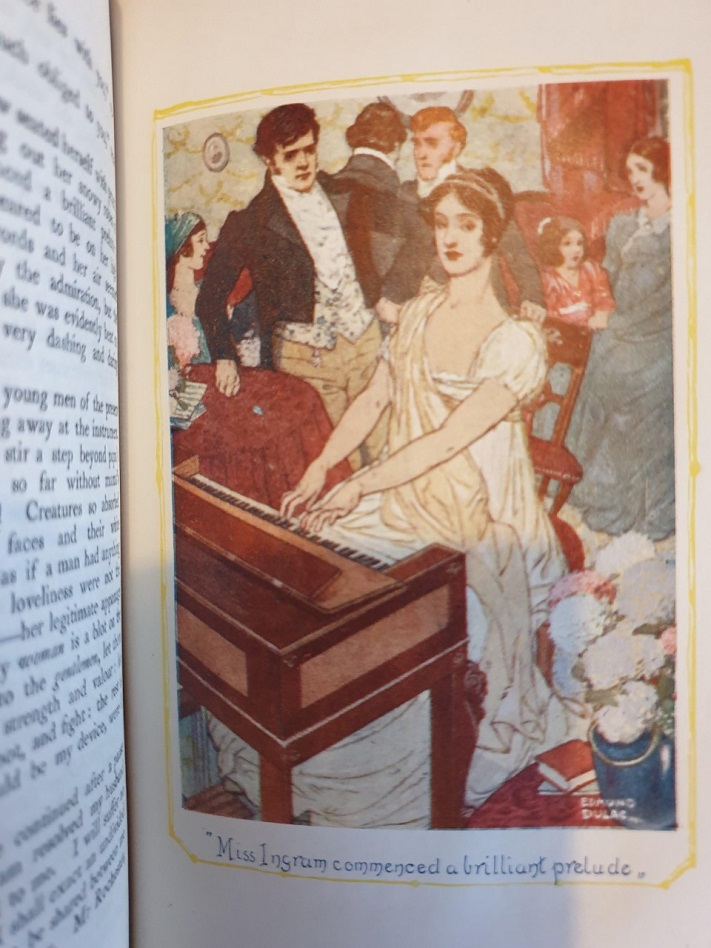

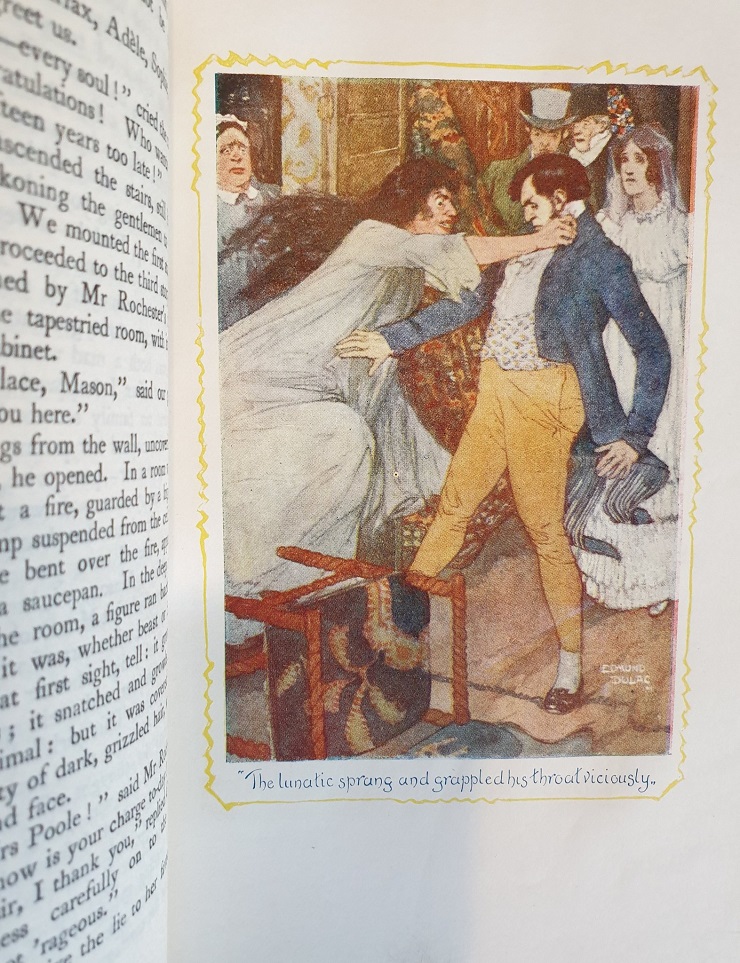

This weekend saw the anniversary of a very special day in the Brontë story, and in the story of English literature as a whole. On 16th October 1847 Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë was published by Smith, Elder & Co. Its success was instant and yet has proven enduring, so in today’s post we’re going to look at Charlotte’s comments in the aftermath of the book’s publication, accompanied by some beautiful illustrations from my two volume edition illustrated by Edmund Dulac.

19th October 1847, to Smith, Elder and Co.

‘Gentlemen, the six copies of “Jane Eyre reached me this morning. You have given the work every advantage which good paper, clear type and a seemly outside can supply. If it fails, the fault will lie with the author – you are exempt. I now await the judgement of the press and the public.’

28th October 1847, to W. S. Williams

‘Dear Sir, your last letter was very pleasant to me to read, and is very cheering to reflect on. I feel honoured in being approved by Mr. Thackeray because I approve Mr. Thackeray. This may sound presumptuous perhaps, but I mean that I have long recognized in his writings genuine talent such as I admired, such as I wondered at and delighted in… One good word from such a man is worth pages of praise from ordinary judges.

You are right in having faith in the reality of Helen Burns’s character: she was real enough: I have exaggerated nothing there: I restrained from recording much that I remember respecting her, lest the narrative should sound incredible. Knowing this, I could not but smile at the quiet, self-complacent dogmatism with which one of the journals lays it down that “such creations as Helen Burns are very beautiful but very untrue.”

The plot of “Jane Eyre” may be a hackneyed one; Mr. Thackeray remarks that it is familiar to him; but having read comparatively few novels, I never chanced to meet with it, and I thought it original…

I would still endeavour to keep my expectations low regarding the ultimate success of “Jane Eyre”; but the desire that it should succeed augments – for you have taken much trouble about the work, and it would grieve me seriously if your active efforts should be baffled and your sanguine hopes disappointed.’

6th November 1847, to W. S. Williams

‘Dear Sir, I shall be obliged if you shall direct the enclosed to be posted in London, as at present I wish to avoid giving any clue to my place of residence, publicity not being my ambition.

It is an answer to the letter I received yesterday, favoured by you; this letter bore the signature of G. H. Lewes, and the writer informs me that it is his intention to write a critique on “Jane Eyre” for the Decbr. number of Frazer’s Magazine – and possibly also, he intimates, a brief no for the Westminster Review. Upon the whole he seems favourably inclined to the work though he hints disapprobation of the melo-dramatic portions.

Can you give me any information respecting Mr. Lewes? What station he occupies in the literary world and what works he has written? He styles himself “a fellow-novelist”. There is something in the candid tone of his letter which inclines me to think well of him.’

6th November 1847, to G. H. Lewes

‘Dear Sir, your letter reached me yesterday; I beg to assure you that I appreciate fully the intention with which it was written, and I thank you sincerely both for its cheering commendation and valuable advice.

You warn me to beware of Melodrame and you exhort me to adhere to the real. When I first began to write, so impressed was I with the truth of the principles you advocate that I determined to take Nature and Truth as my sole guides and to follow in their very footprints; I restrained imagination, eschewed romance, repressed excitement; over-bright colouring too I avoided, and sought to produce something which should be soft, grave and true. My work (a tale in 1 vol) being completed, I offered it to a publisher. He said it was original, faithful to Nature, but he did not feel warranted in accepting it, such a work would not sell.’

10th November 1847, to W. S. Williams

‘Dear Sir, I have received the Britannia and the Sun, but not the Spectator, which I rather regret, as censure, though not pleasant, is often wholesome. Thank you for your information regarding Mr. Lewes. I am glad to hear that he is a clever and sincere man; such being the case, I can await his critical sentence with fortitude: even if it goes against me, I shall not murmur; ability and honesty have a right to condemn where they think condemnation is deserved. From what you say, however, I trust rather to obtain at least a modified approval.

Your account of the various surmises respecting the identity of the brothers Bell, amused me much: were the enigma solved, it would probably be found not worth the trouble of solution; but I will let it alone; it suits ourselves to remain quiet and certainly injures no one else.’

17th November 1847, to W. S. Williams

‘Dear Sir, the perusal of the Era gave me much pleasure, as did that of the People’s Journal. An author feels particularly gratified by the recognition of a right tendency in his works; for if what he writes does no good to the reader, he feels he has missed his chief aim, wasted, in a great measure, his time and labour. The Spectator seemed to have found more harm than good in “Jane Eyre”, and I acknowledge that distressed me a little.

I am glad to be told that your are not habitually over-sanguine: I shall now permit myself to encourage a little more freely the hopeful sentiment which your letters usually impart, and which hitherto I have always tried to distrust. Still I am persuaded every nameless writer should “rejoice with trembling” over the first doubtful dawn of popular good-will; and that he should hold himself prepared for change and disappointment: Critics are capricious, and the Public is fickle; besides one work gives so slight a claim to favour.’

1st December 1847, to Messrs. Smith, Elder and Co.

‘Gentlemen, the Examiner reached me to-day; it had been missent on account of the direction which was to Currer Bell, Care of Miss Brontë. Allow me to intimate that it would be better in future not to put the name of Currer Bell on the outside of communications; if directed simply to Miss Brontë they will be more likely to reach their destination safely. Currer Bell is ‘not’ known in this district and I have no wish that he should become known.

The notice in the Examiner gratified me very much; it appears to be from the pen of an able man who has understood what he undertakes to criticise; of course approbation from such a quarter is encouraging to an Author and I trust it will prove beneficial to the work. I am Gentlemen, yours respectfully, C Bell.’

We can see, as always, what a wonderful letter writer Charlotte Brontë was, but we can see much more as well. There are practical matters, such as the fact that Charlotte didn’t know who G. H. Lewes was and had to enquire as to his character and writing prowess. Lewes is much better known today not for his own literary output, or his work as a critic, but as the common law husband of Mary Ann Evans – the writer George Eliot. When Charlotte finally met Lewes, after the death of her siblings, she wrote that she was moved to tears because of his facial resemblance to Emily Brontë.

We also get a glimpse into Charlotte’s emotions after the publication of Jane Eyre; it seems incredible to us today, but Charlotte was worried about whether it would be a success, and whether it was good enough to justify the time and money her publishers had invested in it. She was beset by doubts even at the height of her success, the ‘imposter syndrome’ that so many writers and artists have to struggle with.

Winter draws near, so there’s never been a better time to re-read Jane Eyre or re-watch one of its brilliant adaptations. Nevertheless I hope you can find time to join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.