Charlotte Brontë has become known, quite rightly, as one of the greatest prose writers the English language has ever seen. Along with the works of her sisters Emily and Anne Brontë her works continue to be read across the globe, and Jane Eyre alone has been translated into at least 57 languages (it could be 58 by now if a Klingon version has appeared). There was one language Charlotte loved more than any other, however, so today we’re going to look at Charlotte Brontë’s love of French (and don’t worry, you won’t need to understand a word of it to read this post).

One reason for the timing of today’s post is that this week marks the anniversaries of two very different letters that Charlotte Brontë wrote in the French language, the first of which is one of the earliest letters from Charlotte which remains extant.

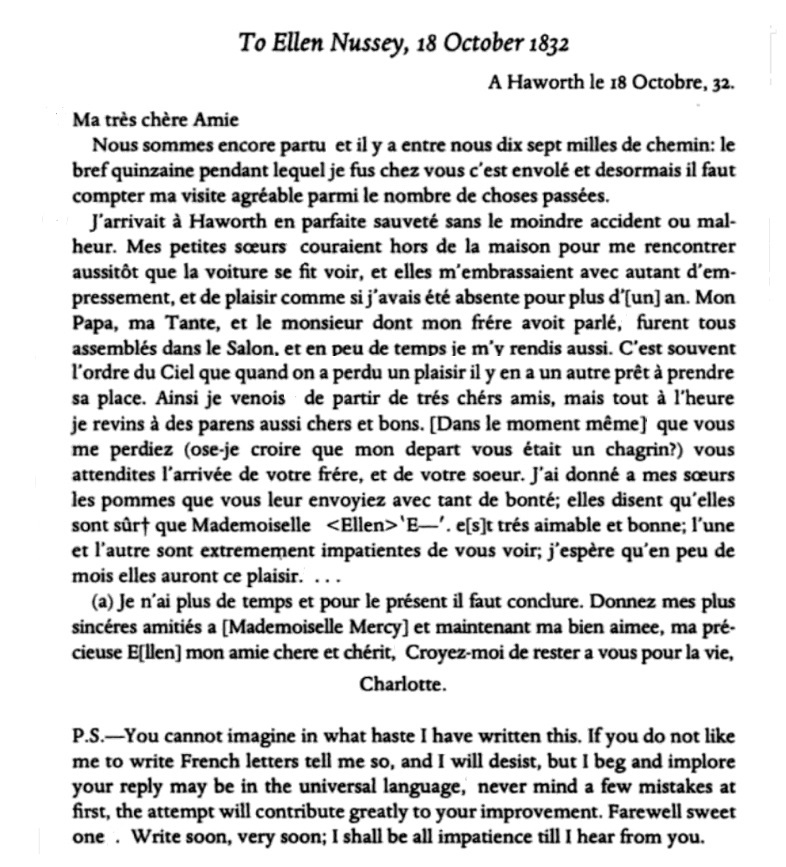

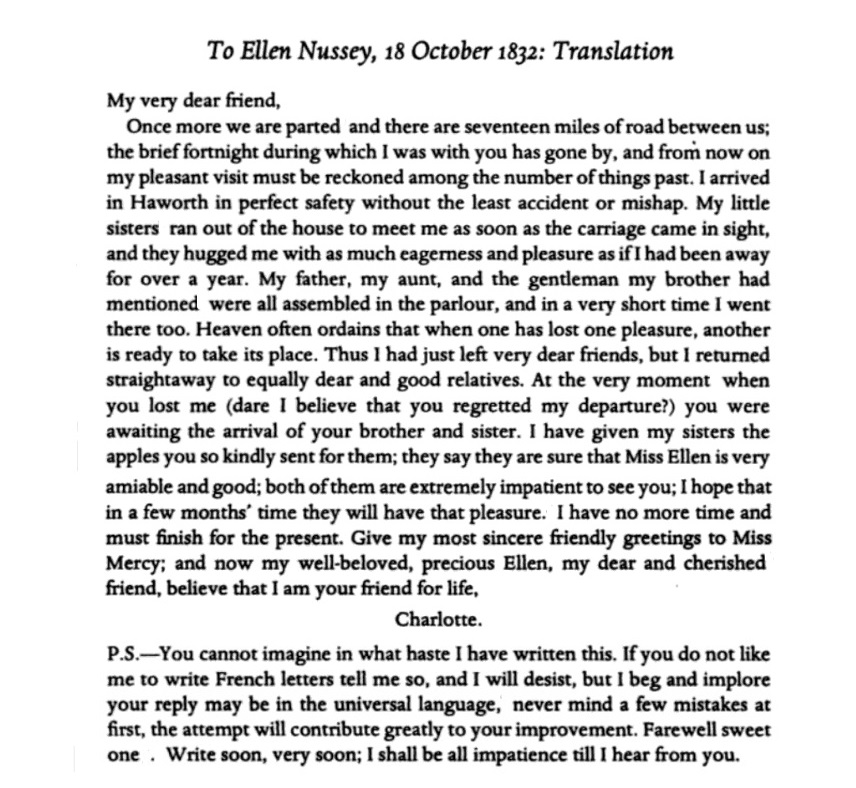

On 18th October 1832 16 year old Charlotte was writing to Ellen Nussey, the great friend she had made upon her entrance to Roe Head school near Mirfield a year earlier. Charlotte has by this time left the school (although she will soon return as a teacher there) but she is still keeping up with her lessons, and insisting that Ellen does too:

A sweet, loving letter in the aftermath of a visit to Ellen’s home, and although Charlotte begs Ellen to at least try to use the ‘universal language’ in her reply I’m placing the English translation below:

We see then that the love of French was ingrained in Charlotte from her youth onwards, and it never really left her. It was this that made Charlotte long to enter school in a French speaking country in 1842, so that she could hone her skills in this language and then pass them on to pupils in the school she was then planning on setting up with her sisters. Eventually Charlotte and Emily Brontë ended up at the Pensionnat Heger in Brussels, but at one point they were destined to attend a school in Lille in northern France. On 20th January 1842 she wrote to Ellen:

‘We expect to leave England in less than three weeks – but we are not yet certain as to the day as it will depend upon the convenience of a French lady now in London Madame Marzials under whose escort we are to sail. Our place of destination is changed. Papa received an unfavourable account from Mr or rather Mrs Jenkins of the French schools in Bruxelles – representing them as of an inferior caste in many respects. On further inquiry an institution in Lille in the north of France was highly recommended by Baptist Noel & other clergymen – and it is to that place it is decided that we are to go.’

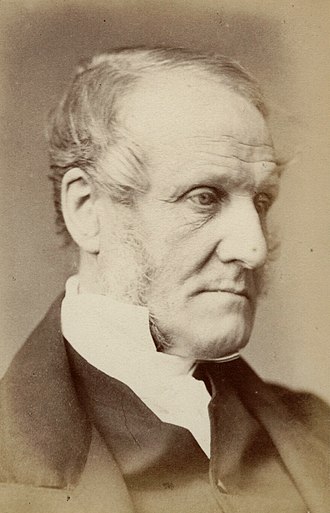

Despite the advice of Mrs Jenkins and Baptist Noel (an Anglican priest of aristocratic stock who was seen as one of the leaders of the evangelical movement) Charlotte and Emily left for Brussels, not Lille, three weeks later. It was in Brussels, of course, that Charlotte encountered her great unrequited love Constantin Heger, a man who did little to dampen her admiration of the French language.

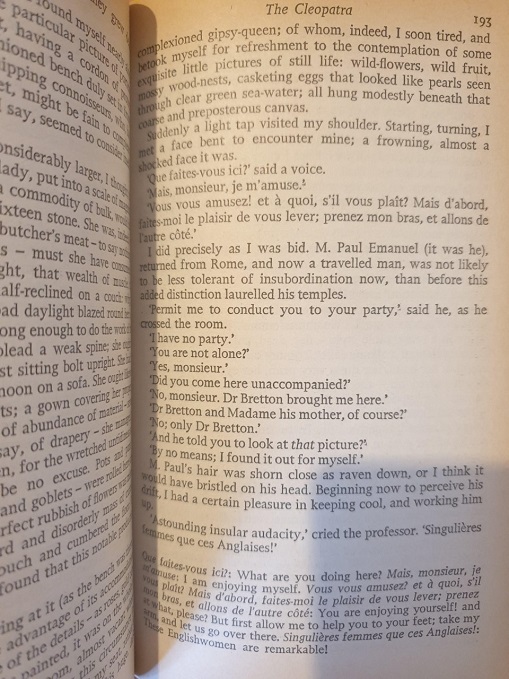

Thus we find French used in all her novels, and extensively so in The Professor and Villette. Her publisher George Smith begged her to allow the use of translated passages after her French ones, but Charlotte stood firm and insisted on French only in the passages she had so written. Like Ellen Nussey in 1832, her readers must learn to be more proficient in the ‘universal language’. Fortunately for readers such as myself whose French is more ‘sacre bleu!’ than ‘ooh la la!’ we can now buy versions that do contain English translations, such as in my 1973 copy of Villette below. Even so, most editions still adhere to Charlotte’s instruction, which can lead to readers wishing that Charlotte was rather less enamoured of the French language:

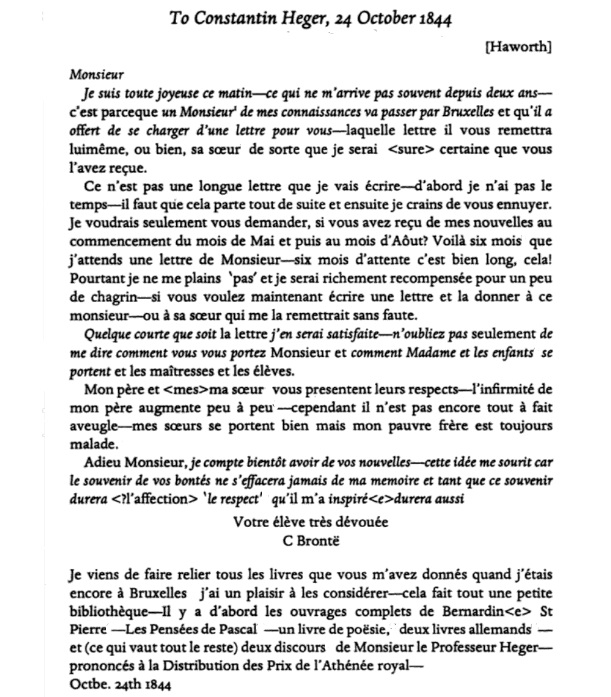

We come now to Charlotte’s second letter with an anniversary this week – in fact it was on this day 1844 that Charlotte Brontë wrote the following letter to Constantin Heger:

And in English (courtesy of brilliant Brontë editor and expert Margaret Smith): ‘Sir, I am full of joy this morning – something which has rarely happened to me these last two years – it is because a gentleman of my acquaintance will be passing through Brussels and has offered to take charge of a letter to you – which either he or else his sister will deliver to you, so that I shall be certain you have received it.

I am not going to write a long letter – first of all I haven’t the time, it has to go immediately – and then I am afraid of boring you. I would just like to ask you whether you have heard of me at the beginning of May and then in the month of August? For all those six months I have been expecting a letter from you, Monsieur – six months of waiting. That is a very long time indeed! Nevertheless I am not complaining and I shall be richly recompensed for a little sadness if you are now willing to write a letter and give it to this gentleman – or to his sister – who would deliver it to me without fail.

However short the letter may be I shall be satisfied with it – only do not forget to tell me how you are, Monsieur, and how Madame and the children are and the teachers and pupils.

My father and sister send you their regards – my father’s affliction is gradually increasing, however he is still not completely blind; my sisters are keeping well but my poor brother is always ill.

Goodbye Monsieur, I am counting on soon having news of you – this thought delights me for the remembrance of your kindness will never fade from my memory and so long as this remembrance endures, the respect it has inspired in me will endure also.

Your very devoted pupil, C. Brontë

I have just had bound all the books that you gave me when I was still in Brussels. I take pleasure in looking at them – they make quite a little library. First there are the completed works of Bernardin de St. Pierre, the Pensees of Pascal, a book of verse, two German books, and (something worth all the rest) two speeches, by Professor Heger – given at the Prize Distribution of the Athénée Royal.’

A letter full of hope and joy, but in retrospect full of sadness as not only did this letter receive no reply it was one of the missives which were ripped up, presumably by Monsieur Heger, and then stitched back together by his wife. Without Charlotte’s love of the French language she may never have been inspired to go to Brussels, never have met Constantin Heger and never have written the characters he inspired such as Paul Emanuel and Edward Rochester.

Whatever language you read your Brontë books in I hope you enjoy them, and I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.