Christmas is nearly upon us, and of course an extra reason for celebration has arrived as we got the news this week that the Honresfield library collection of literary treasures has been saved for the nation rather than being sold to the highest bidder. Great news, but this day in 1848 brought tragic news to Haworth Parsonage: it was at 2pm on this day 173 years ago that Emily Brontë died.

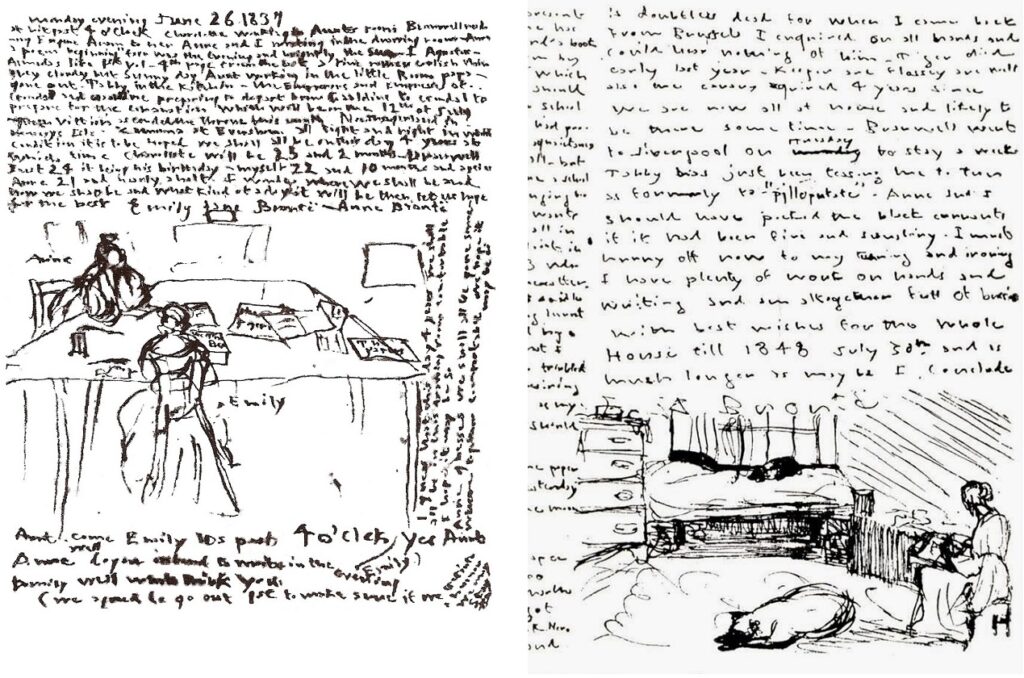

We will not dwell too long on Emily’s final illness, on her brave determination not to be cowed by consumption; that is something Emily’s family had to struggle with. Instead, let us pay tribute to Emily’s life and work. If her life seemed, on the surface, unremarkable, her work was truly remarkable. In today’s new post we’re going to look at what some of those who knew Emily Brontë had to say about her, as well as showcasing some of her artistic productions.

Charlotte Brontë

‘In Emily’s nature the extremes of vigour and simplicity seemed to meet. Under an unsophisticated culture, inartificial tastes, and an unpretending outside, lay a secret power and fire that might have informed the brain and kindled the veins of a hero.’

Ellen Nussey

‘Emily had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte’s, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes, kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you: she was too reserved. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption…

I have at this time before me the history of a mighty and passionate soul, whom every adventure that makes for the sorrow or gladness of man would seem to have passed by with averted head. It is of Emily Brontë I speak, than whom the first 50 years of this century produced no woman of greater or more incontestable genius.’

John Greenwood

‘Patrick had such unbounded confidence in his daughter Emily that he resolved to learn her to shoot too. They used to practice with pistols. Let her be ever so busy in her domestic duties, whether in the kitchen baking bread at which she had such a dainty hand, or at her studies, rapt in a world of her own creating – it mattered not; if he called upon her to take a lesson, she would put all down. His tender and affectionate “Now, my dear girl, let me see how well you can shoot today”, was irresistible to her filial nature and her most winning and musical voice would be heard to ring through the house in response, “Yes, papa” and away she would run with such a hearty good will taking the board from him, and tripping like a fairy to the bottom of the garden, putting it in its proper position, then returning to her dear revered parent, take the pistol which he had primed and loaded for her. “Now my girl” he would say, “take time, be steady”. “Yes papa” she would say taking the weapon with as firm a hand, and as steady an eye as any veteran of the camp, and fire. Then she would run to fetch the board for him to see how she had succeeded. And she did get so proficient, that she was rarely far from the mark. His “how cleverly you have done, my dear girl”, was all she cared for. “Oh!” He would exclaim, “she is a brave and noble girl. She is my right-hand, nay the very apple of my eye!”

Sarah Wood

‘“Do I remember the Brontës?” was her greeting. “I should rather think I did. Miss Charlotte was my Sunday-school teacher. She was nice. But Miss Anne was my favourite: such a gentle creature.” “And Miss Emily?” Miss Parry asked. “Oh, you see, ma’am, I don’t know much about Miss Emily, she was very shy; but Martha loved her: she said she was so kind.”’

Martha Brown

‘Many’s the time that I have seen Miss Emily put down the tally-iron as she was ironing the clothes to scribble something on a piece of paper. Whatever she was doing, ironing or baking, she had her pencil and paper by her. I know now that she was then writing Wuthering Heights. Poor Emily, we always thought to be the best-looking, the cleverest, and the bravest-spirited of the three. Little did we dream that she would be the first to be taken away.’

Constantin Heger

‘She should have been a man – a great navigator. Her powerful reason would have deduced new spheres of discovery from the knowledge of the old; and her strong, imperious will would never have been daunted by opposition or difficulty; never have given way but with life.’

Halliwell Sutcliffe

‘“Emily Brontë,” says Mr. Sutcliffe, “was perhaps the bravest woman of her generation. Shame she abhorred, and to stand secure in one’s own strength was peculiarly her gospel.” He speaks of “Emily, the genius; Charlotte, the half-genius; and Branwell, the clever ne’er-do-weel who chose to wear motley all his days, when better raiment was at his service.”

Speaking of Emily Brontë, he continues, “She was neither worldly-wise nor eager for publicity, on the contrary her life to the last detail exhibits a reserve that was almost cloister-like, a self-dependence that was scarcely human, an integrity that disdained, not the great shams of life alone, but even the trickeries of social intercourse.

See her out yonder on the loneliest moor of Yorkshire – gaunt of figure, free of stride, not beautiful to look at until one saw the deep far-seeing eyes, with the light in them that comes from lonely, lover-like communion with the larger nature. See her climb the slopes, and walk knee-deep in ling, and halt just now and then to drink in the wild sweet wind, to scent the bracken, or watch the mystic purple creep out at foaming tide above the distant hills. Is this a woman to seek pseudo-fame by trickery? Or is she one who has kept long watches with her mother, Nature, who has sorrowed and rejoiced with her, who has wept with the weeping skies and laughed with the laughing sun, who, finally, has passed her soul through furnaces impossible to weaker natures and is ready to bring to birth a book of vital and surpassing charm.”’

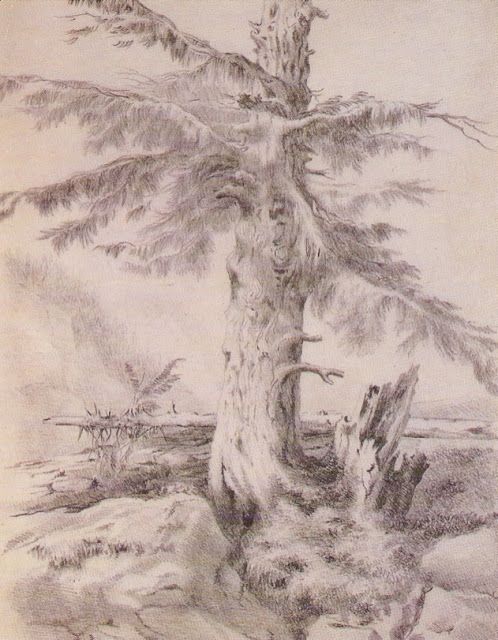

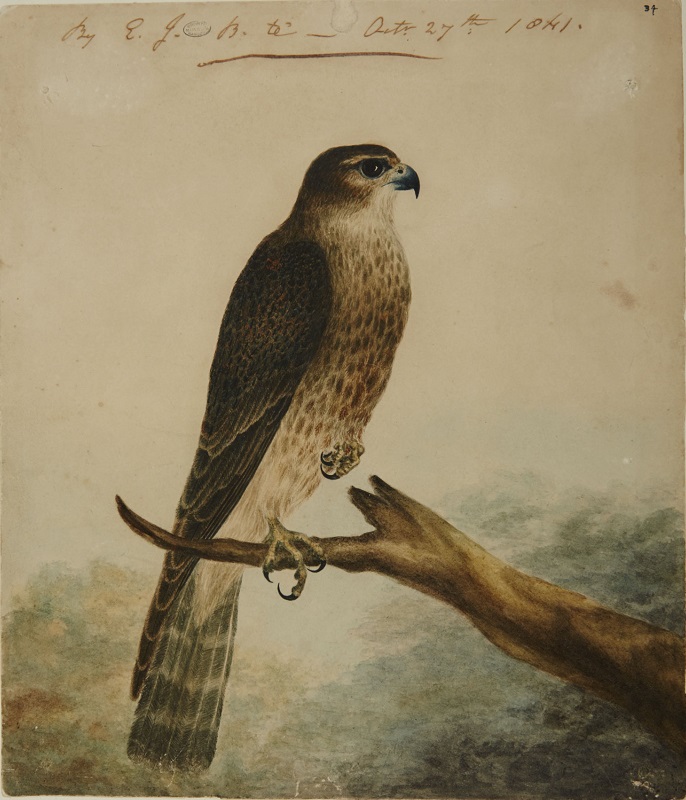

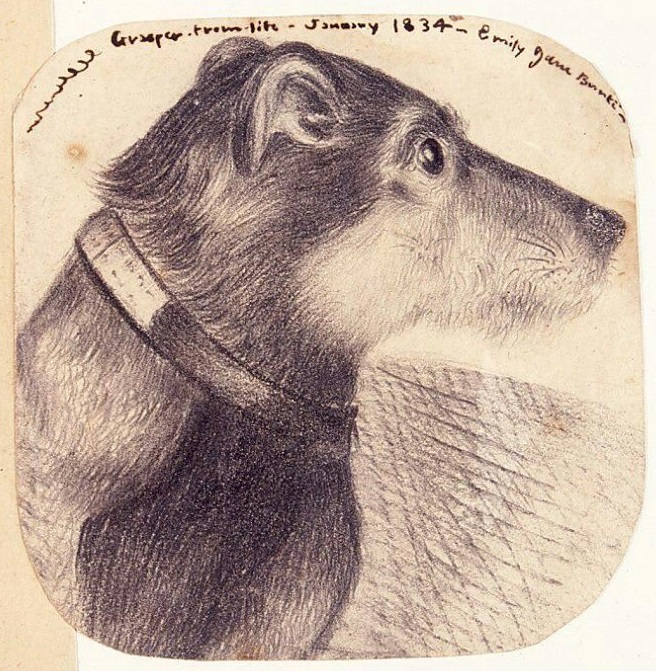

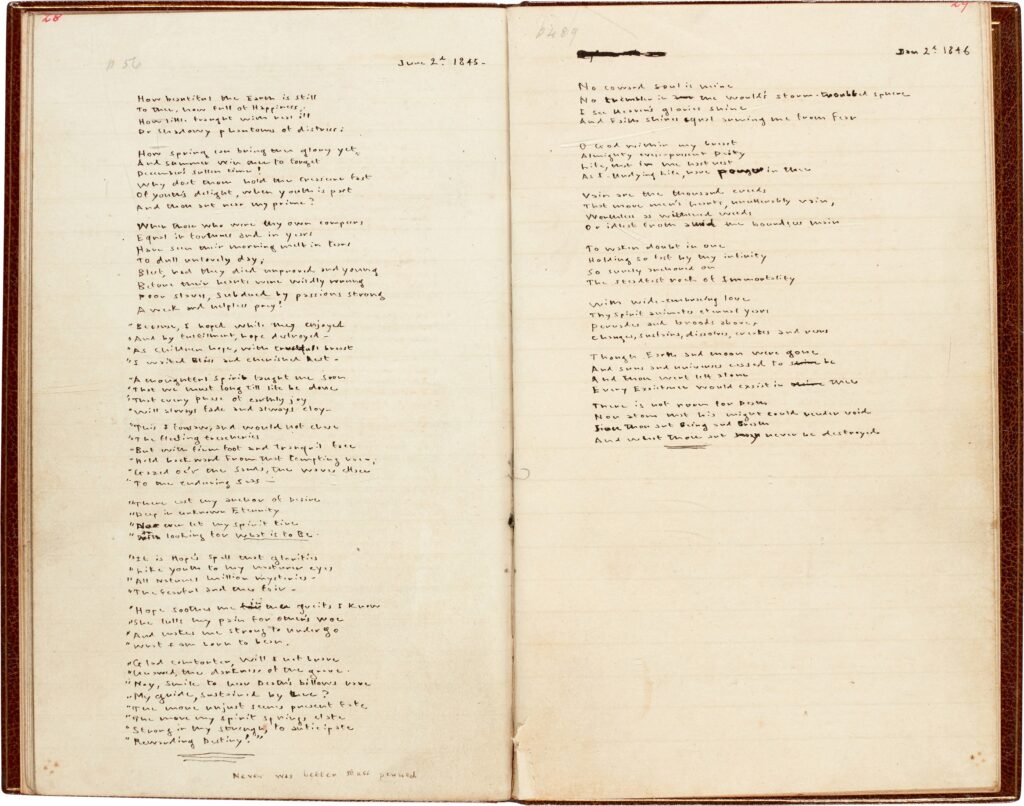

Emily Brontë was a great poet, an excellent artist, a brilliant pianist, a fabulous bread maker, superb at learning languages, oh, and she also happened to write what may just be the greatest novel ever written. Emily Brontë truly was a unique genius: whatever she turned her hand to, she quickly excelled at. Let’s remember the talents of Emily Brontë and her family today, and look forward with joy to the festive celebrations to come. I hope to see you next Saturday for a special Christmas Brontë blog post.