It’s my opinion that a person’s literary discernment tells you a lot about them. We all have different tastes in reading matter but if they’re not into books at all, or art or theatre or the things that make life bearable, then they’re not going to interest me. That’s why I’ve always felt gratified by the story of Mr Enoch and his love of the Brontës’ first literary outing – and that’s what we’re going to look at in today’s post before veering aside to look at what the sisters’ handwriting might say about their personalities!

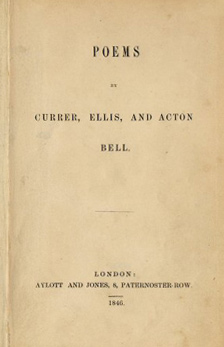

Charlotte, Emily and Anne began their career as published writers in 1846 when Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell hit the shelves and circulating libraries. The story is well known of how this historic literary moment came about: Charlotte ‘accidentally’ discovered Emily Brontë’s secret poetry manuscript, realised how wonderful they were, and, after a blazing row, the sisters eventually decided to try to find a publisher for their joint poetic creations.

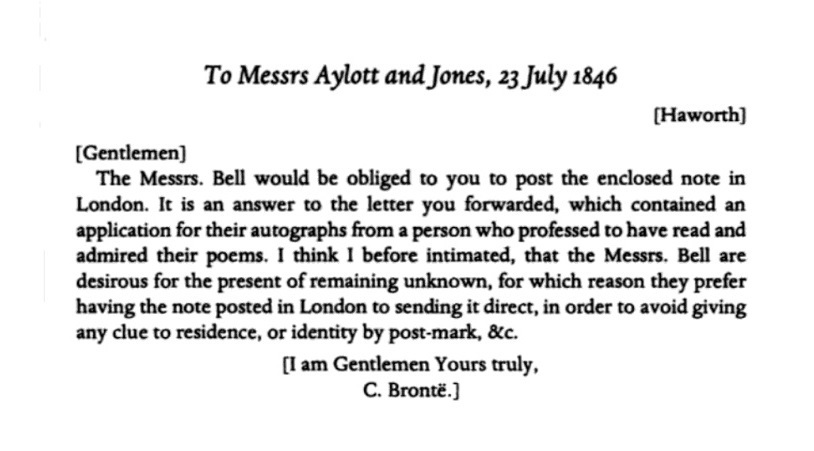

A publisher was found in the shape of Aylott & Jones of Paternoster Row, but the Brontës had decided that they wanted to publish the work anonymously and took on the pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. The book gained good reviews, but sales were far from promising – in fact it initially sold only two copies (although every copy was eventually sold after Smith, Elder & Co bought the rights and relaunched it). This must have seemed a bit of a blow to Charlotte Brontë in particular, the driving force behind the decision to publish their poetry but their spirits must have lifted slightly on this very week in 1846 when word came from Aylott & Jones that one of the two purchasers had enjoyed the collection so much that he’d requested the autographs of its authors! That man was a Mr Enoch of Warwick, and we have Charlotte’s response to the request written on 23rd July 1846:

We see then that Messrs Bell, the versifying Bell brothers, were communicating with their publisher via a mysterious intermediary – one C. Brontë, whoever that could be? So desirous were they of remaining anonymous that they sent the autographs to Aylott and Jones and asked them to post it on, so that their postmark wouldn’t give any clues as to their location.

Mr Enoch must have been thrilled when the signatures came, and it was just reward for him in his discernment when it came to poetry, but just who was he? His full name was Frederick Enoch, and he was something of a wordsmith himself. The son of a cordwainer (boot maker) and auctioneer, from an early age Frederick took an interest in literature, and by 1851 the census described him as a ‘printer, stationer and shop assistant’.

It seems, however, that Frederick longed to be a writer himself rather than simply selling writing, and there was one particular area he specialised in: songs. A number of songs from the mid-nineteenth century are attributed to him, including ‘Sweet Vesper Hymn’ and ‘My Sweetheart When A Boy’, which gained some popularity in its time. This song was penned in 1870 when Enoch was 43, so too late for the Brontës to have known, but it still endures to this day. We not only know the name of the song and its words, we actually have a modern recording of it thanks to Professor Derek B. Scott of the University of Leeds. Here’s a link to the recording on the wonderful Victorian Web website, and it’s well worth listening to: https://victorianweb.org/mt/parlorsongs/42.html

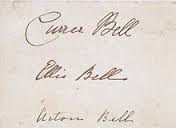

Mr Enoch is best known today, however, for his autograph request to the Brontë sisters, as it was his letter and the subsequent reply which gives us the only existing signatures of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë using their pen names – and here they are:

What do these signatures tell us about the Brontës, other than their great wish for anonymity? What does the handwriting of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë reveal? Perhaps the answer can be found in graphology? Graphology is a study which believes that handwriting reveals a lot about the person responsible for it. I feel this is something Charlotte Brontë would have been a fan of, as she was a great believer in phrenology, the reading of bumps on the head. Which leads me to a slight detour which may be of interest to American readers of this blog. I had great fun talking about Charlotte Brontë and phrenology with Gyles Brandreth for an excellent television documentary entitled ‘Brontë’s Britain With Gyles Brandreth’; I’m pleased to report that this documentary is now being shown Stateside on PBS, under the new name of ‘In The Footsteps Of The Brontës’, so do look out for it if you get the chance.

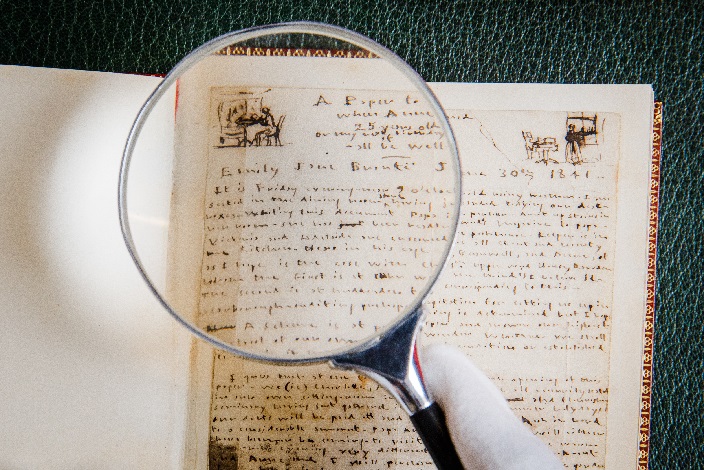

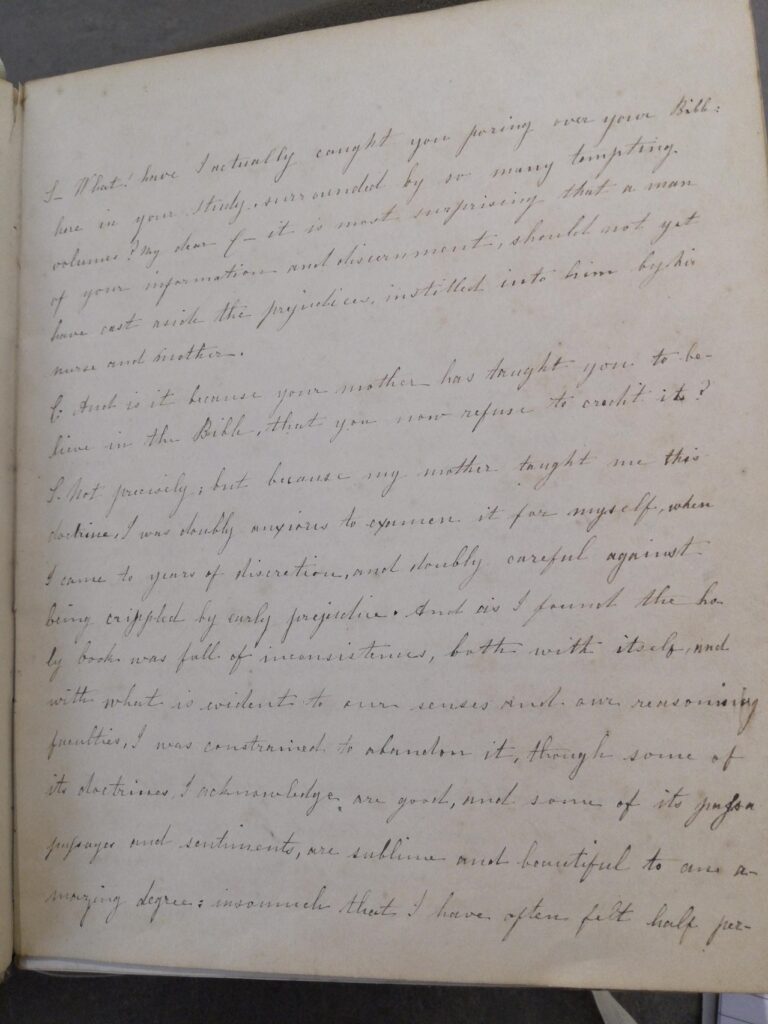

Back to graphology. I had long been of the belief that a piece of writing in the archives of Brotherton Library, Leeds was by Anne Brontë – in fact that it was the last piece of writing she ever produced. At the time it was unattributed, but now it’s listed as being by Anne Brontë – and the essay and my views on it are contained in my book Craving The Rose: Anne Brontë At 200.

As part of my effort to prove it was by Anne I enlisted a handwriting expert called Jean Elliott and sent her a sample of the piece in question along with three handwriting samples known to be by Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. The pieces were anonymised, but Jean had no hesitation in confirming what I knew – the article in question was by the author of sample A which I had submitted: it was Anne Brontë.

Jean is a handwriting expert who has often been called upon as a legal expert in court cases, but she is also a graphology specialist, and after I revealed the identities of the three subjects she gave the interesting analysis below:

‘The sisters handwriting show a strong right slant and a certain rigidity and discipline recorded in the production of the letter. Anne – Line construction is very rigid and her lines are so straight . (all three girls show elements of rigidity in their scripts but Anne’s seem more so.) Charlotte – Headline Author of line 5 word advise and line 7 word ‘renders’ letter ‘d’ over emotional nature – maybe loves singing. In my opinion she is more artistic than her sister. When a writer produces a small middle zone (this is the zone that records what is happening in the here and now- e.g. everyday affairs, i.e. Anne can cut off her personal needs and pour effort into aims and ambitions to achieve recognition and success. Letter f with a long lower zone Practical – self reliant. Interestingly both Charlotte and Anne show a small middle zone with an extended upper and lower zone. If we look at all the three girls samples all three share this syndrome.’

So the graphology view is that Charlotte was the most artistic of the sisters, and that Anne was more capable of putting her personal needs to one side in order to achieve success. All three sisters are practical and self reliant. An interesting analysis, although of course we know much more about the sisters today than, for example, Frederick Enoch did when he unwittingly asked for their autographs.

I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post, and be thankful that you don’t have to see my handwriting – a scrawl which even I struggle to decipher at times!