Things didn’t always run smoothly in the world of the Brontës, as we shall soon see in the subject of today’s new Brontë blog post. Things didn’t go smoothly for this website with last week’s post either. After a WordPress update it seems that the post displayed on desktop sites but not on mobile sites, so apologies if you were affected by this – hopefully all should be okay now.

One period that Charlotte Brontë found particularly trying in her life was her time as a teacher at Roe Head school in the hills above Mirfield in the West Riding of Yorkshire (that’s a drawing of it, by Anne Brontë at the head of this post). Charlotte had attended the school as a pupil from 1831 until 1832; it was a very happy time for her, and she made lifelong friends in Ellen Nussey and Mary Taylor. In 1835 Charlotte returned to Roe Head in the role of teacher, but she found this to be a very different experience.

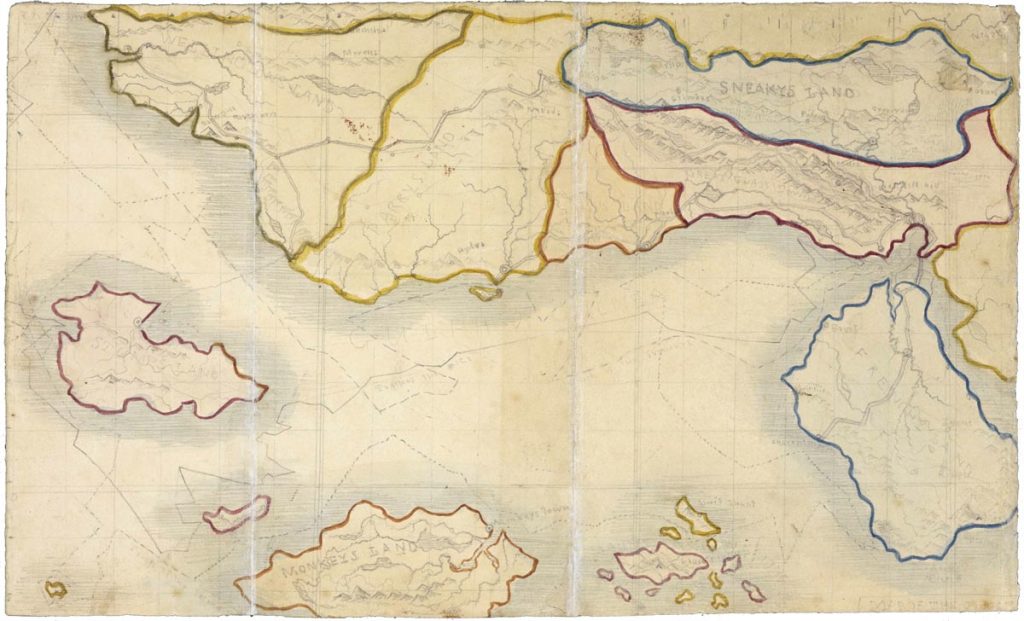

Charlotte, although still in her late teens, was now an adult, and a deep thinker whose mind was preoccupied by thoughts of the real world around her and her role within it, and by the land of Angria which she conjured up from her imagination. As a teacher she found herself frustrated by the inability of her pupils to live up to the standards she herself had set four years earlier and by the time constraints imposed by the role which meant that she had little time to devote to the activity she loved more than anything else: creating new worlds from her own mind.

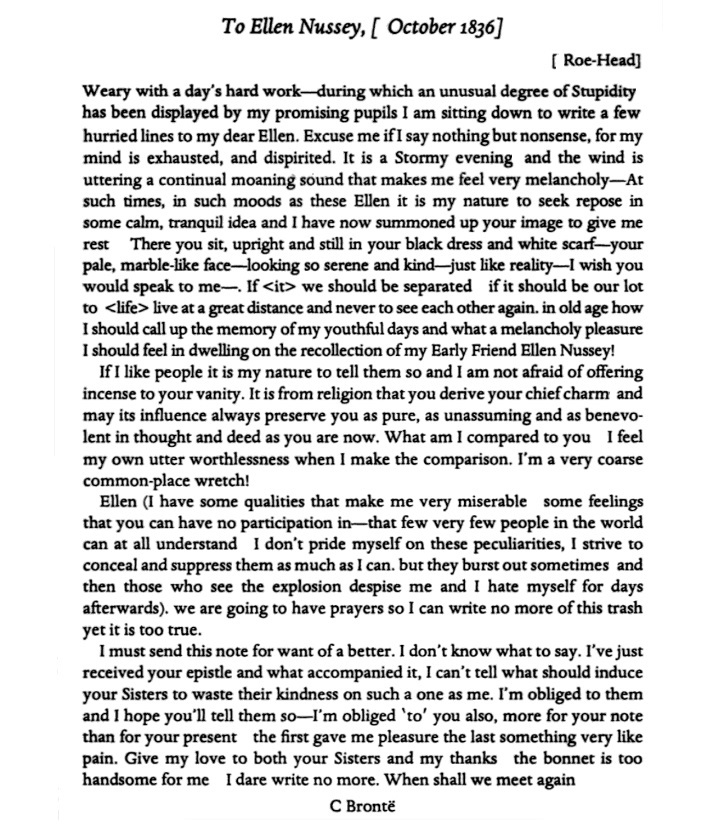

Charlotte expressed her frustrations, and anger, in blistering honesty in what has come to be known as the Roe Head journal, but in fact it was not a diary as such but a series of letters to best friend Ellen Nussey. In these letters she lays bare, with typical honesty, her feelings about herself and others, and it is to one of these letters we turn now, written 186 years ago this month:

There is a deep vein of despair running throughout this letter and others which make up the Roe Head journal. Charlotte Brontë always judged herself harshly and without mercy, and she battled throughout her life against what would today be called ‘imposter syndrome’ – an inability to see the true talents and qualities that others see in you. It is perhaps this that led her publisher and friend George Smith to comment: ‘It may seem strange that the possession of genius did not lift her above the weakness of an excessive anxiety about her personal appearance. But I believe that she would have given all her genius and her fame to have been beautiful. Perhaps few women ever existed more anxious to be pretty than she.’

We see further evidence of this many years later in 1849, after the death of Anne Brontë, when Charlotte looks mournfully back at the passing of all five of her siblings and writes: ‘They [younger sisters Emily and Anne] are both gone, and so is poor Branwell – and Papa has now me only – the weakest, puniest, least promising of his six children.’

Charlotte would doubtless be amazed that after nearly two hundred years her name and work is known and loved across the world, and that we can see the true qualities she possessed: strength, determination, kindness and genius. Perhaps this is something we can all learn from? We all have skills, talents and qualities that make others love us, we just need to step back and see ourselves as they do. I’m certainly very pleased to have you as a reader of my blog and as a fellow Brontë lover, and I hope to see you here next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Excellent love the letter it must have been awful for poor charlotte when all her siblings died, she thought a lot about Ellen Nussey, and it comes across in your email

Thank you, Mr T,Lockwood