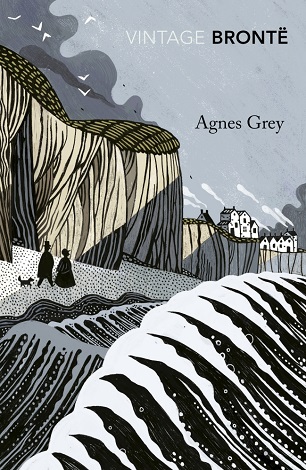

As a great fan of Anne Brontë, as I know you all are, this week is a difficult one. It’s the week in which Anne left this life, but even in her dying days she left lessons for us all: lessons in faith, humility, kindness and charity. These are four elements which summed up Anne’s life in many ways, and thanks to a detailed and very moving account of her last days, we know that they were still at the forefront of Anne’s character even as her death rapidly approved. In today’s post we’re going to look at this very special account: ‘The Last Days Of Dear A.B.’

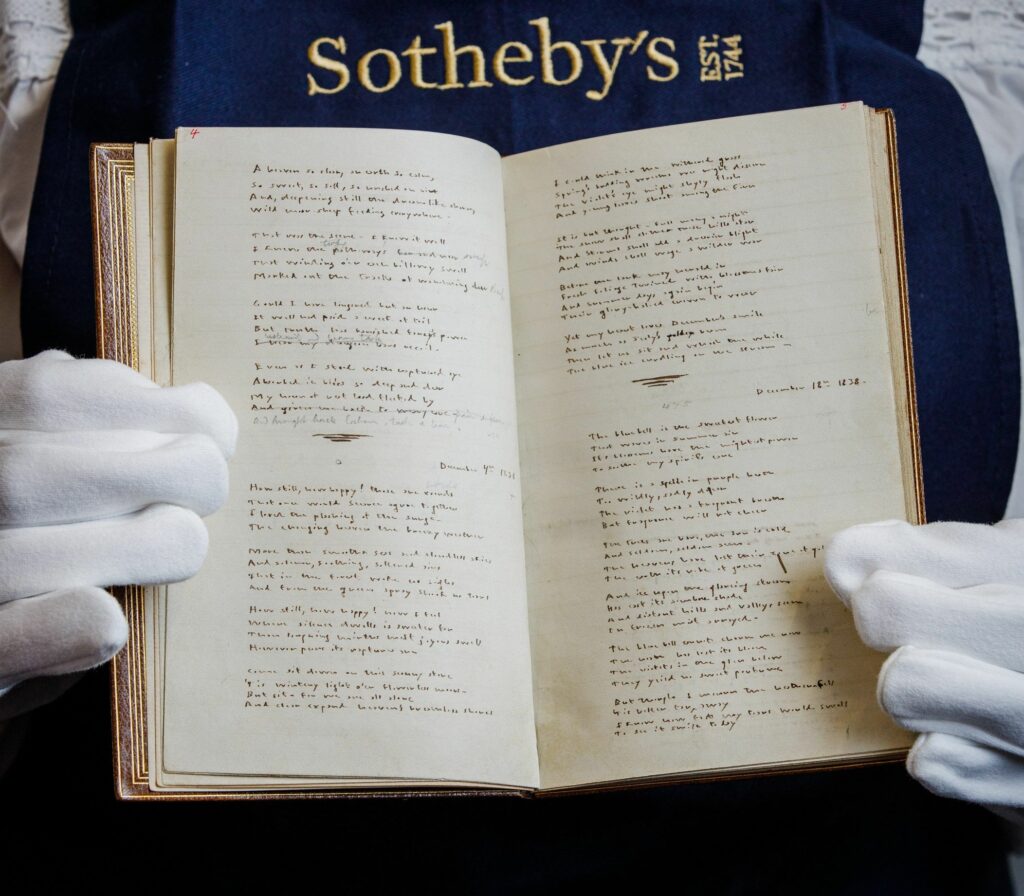

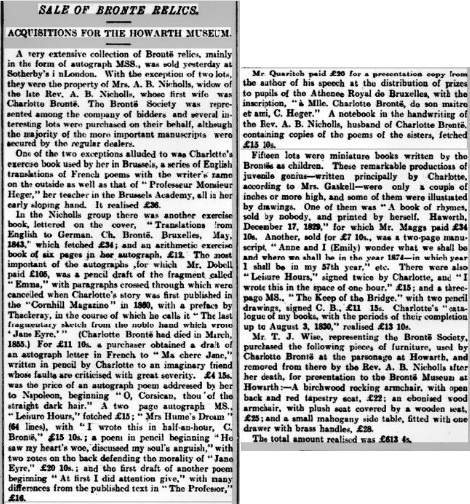

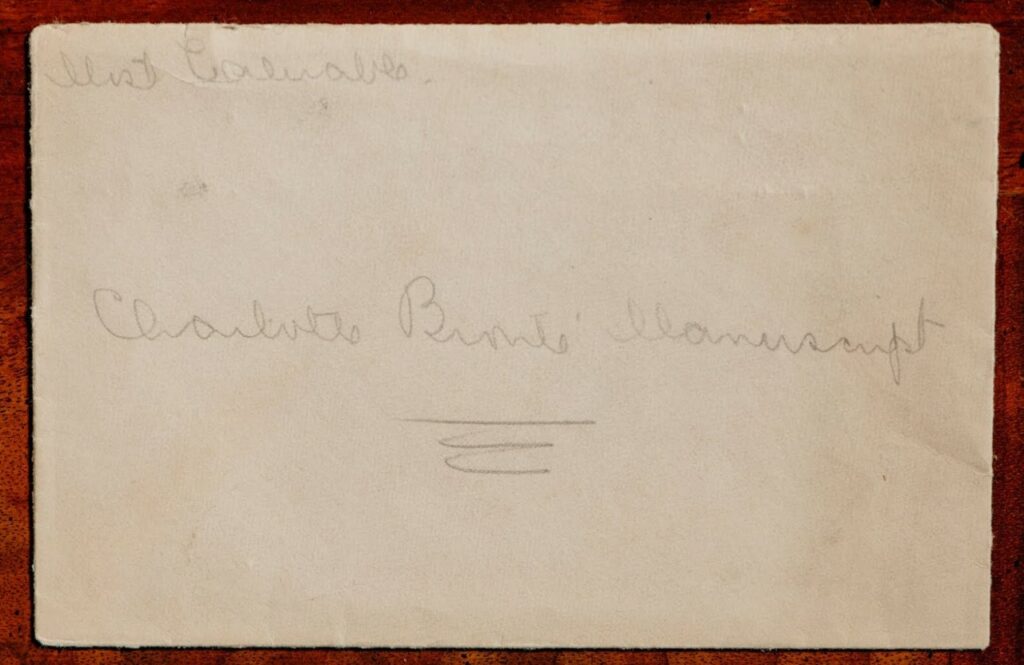

Whilst writing her biography of Charlotte Brontë, Elizabeth Gaskell had asked Ellen Nussey, who was helping her with the book, to provide some details of Charlotte’s journey to Scarborough with Ellen and Anne in May 1849. Those days must still have been vivid in Ellen’s mind, for she gave a thorough, and thoroughly beautiful, account of the final six days of Anne Brontë’s life. The original manuscript is now in the collection of King’s College, Canterbury, but I reproduce it in full below.

‘She left her home May 24th, 1849 – died May 28th. Her life was calm, quiet, spiritual such was her end. Through the trials and fatigues of the journey, she evinced the pious courage and fortitude of a martyr. Dependence and helplessness were ever with her a far sorer trial than hard, racking pain.

The first stage of our journey was to York; and here the dear invalid was so revived, so cheerful, and so happy, we drew consolation, and trusted that at least temporary improvement was to be derived from the change which she had so longed for, and her friends had so dreaded for her.

By her request we went to the Minster, and to her it was an overpowering pleasure; not for its own imposing and impressive grandeur only, but because it brought to her susceptible nature a vital and overwhelming sense of omnipotence. She said, while gazing at the structure, ‘If finite power can do this, what is the…?’ and here emotion stayed her speech, and she was hastened to a less exciting scene. Her weakness of body was great, but her gratitude for every mercy was greater. After such an exertion as walking to her bed-room, she would clasp her hands and raise her eyes in silent thanks, and she did this not to the exclusion of wonted prayer, for that too was performed on bended knee, ere she accepted the rest of her couch.

On the 25th we arrived at Scarborough; our dear invalid having, during the journey, directed our attention to every prospect worthy of notice.

On the 26th she drove on the sands for an hour; and lest the poor donkey should be urged by its driver to a greater speed than her tender heart thought right, she took the reins, and drove herself. When joined by her friend, she was charging the boy-master of the donkey to treat the poor animal well. She was ever fond of dumb things, and would give up her own comfort for them.

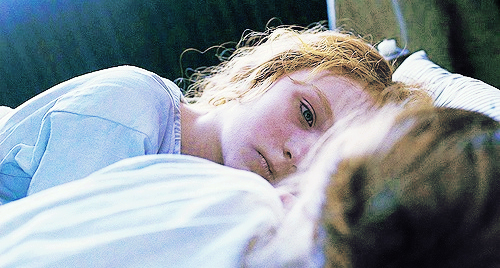

On Sunday, the 27th, she wished to go to church, and her eye brightened with the thought of once more worshipping her God amongst her fellow-creatures. We thought it prudent to dissuade her from the attempt, though it was evident her heart was longing to join in the public act of devotion and praise. She walked a little in the afternoon, and meeting with a sheltered and comfortable seat near the beach, she begged we would leave her, and enjoy the various scenes near at hand, which were new to us but familiar to her. She loved the place, and wished us to share her preference.It closed with the most glorious sunset ever witnessed. The castle on the cliff stood in proud glory gilded by the rays of the declining sun. The distant ships glittered like burnished gold; the little boats near the beach heaved on the ebbing tide, inviting occupants. The view was grand beyond description. Anne was drawn in her easy chair to the window to enjoy the scene with us. Her face became illuminated almost as much as the glorious sun she gazed upon. Little was said, for it was plain that her thoughts were driven by the imposing view before her to penetrate forwards to the region of unfading glory.

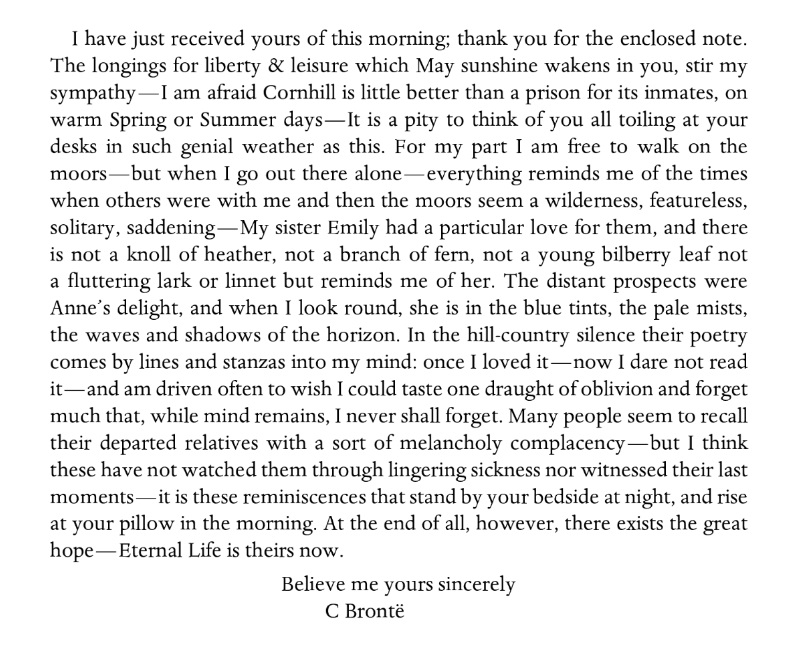

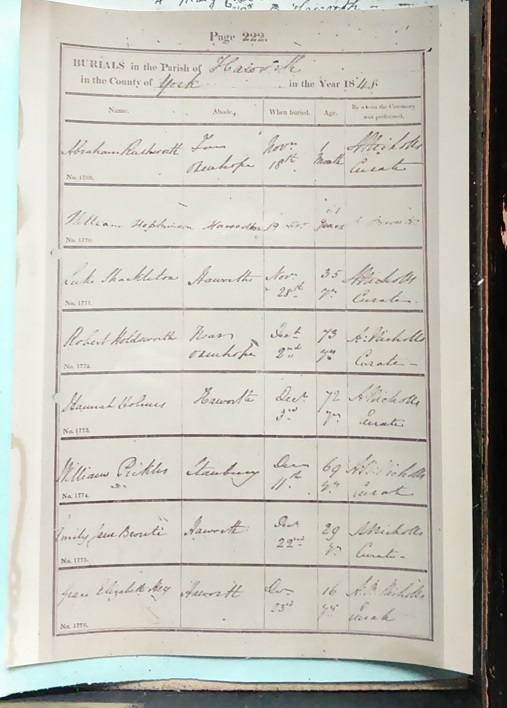

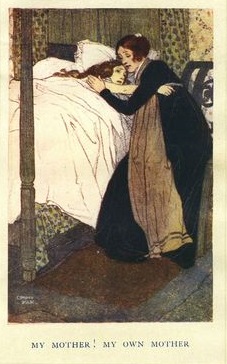

The night was passed without any apparent accession of illness. She rose at seven o’clock, and performed most of her toilet herself, by her expressed wish. Her sister always yielded such points, believing it was the truest kindness not to press inability when it was not acknowledged. Nothing occurred to excite alarm till about 11 a.m. She then spoke of feeling a change. She believed she had not long to live. Could she reach home alive, if we prepared immediately for departure? A physician was sent for. Her address to him was made with perfect composure. She begged him to say how long he thought she might live ; not to fear speaking the truth, for she was not afraid to die. The doctor reluctantly admitted that the angel of death was already arrived, and that life was ebbing fast. She thanked him for his truthfulness, and he departed to come again very soon. She still occupied her easy chair, looking so serene, so reliant: there was no opening for grief as yet, though all knew the separation was at hand. She clasped her hands, and reverently invoked a blessing from on high ; first upon her sister, then upon her friend, to whom she said, ‘ Be a sister in my stead. Give Charlotte as much of your company as you can.’ She then thanked each for her kindness and attention. Ere long the restlessness of approaching death appeared, and she was borne to the sofa ; on being asked if she were easier, she looked gratefully at her questioner, and said, ‘It is not you who can give me ease, but soon all will be well through the merits of our Redeemer.’ Shortly after this, seeing that her sister could hardly restrain her grief, she said, ‘Take courage, Charlotte; take courage.’ Her faith never failed, and her eye never dimmed till about two o’clock, when she calmly and without a sigh passed from the temporal to the eternal. So still, and so hallowed were her last hours and moments. There was no thought of assistance or of dread. The doctor came and went two or three times. The hostess knew that death was near, yet so little was the house disturbed by the presence of the dying, and the sorrow of those so nearly bereaved, that dinner was announced as ready, through the half-opened door, as the living sister was closing the eyes of the dead one.

She could now no more stay the welled-up grief of her sister with her emphatic and dying ‘ Take courage,’ and it burst forth in brief but agonising strength. Charlotte’s affection, however, had another channel, and there it turned in thought, in care, and in tenderness. There was bereavement, but there was not solitude; – sympathy was at hand, and it was accepted. With calmness, came the consideration of the removal of the dear remains to their home resting-place. This melancholy task, however, was never performed; for the afflicted sister decided to lay the flower in the place where it had fallen. She believed that to do so would accord with the wishes of the departed. She had no preference for place. She thought not of the grave, for that is but the body’s goal, but of all that is beyond it.

“Her remains rest,

Where the south sun warms the now dear sod,

Where the ocean billows lave and strike the steep and turf-covered rock.’”

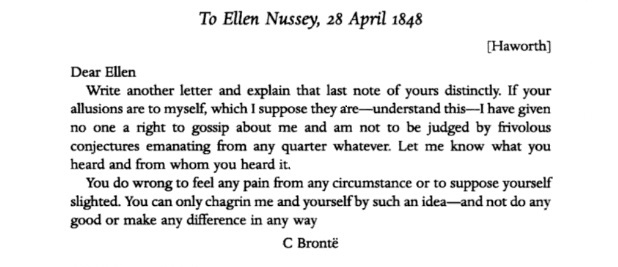

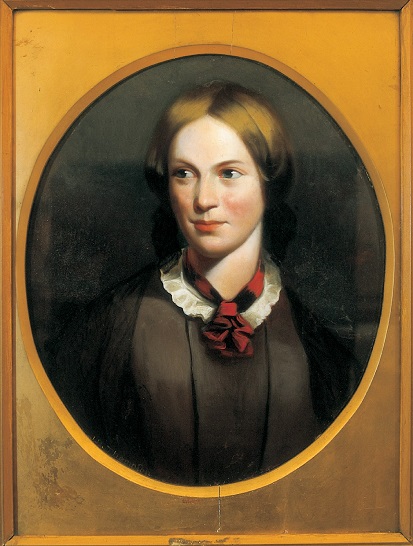

Charlotte Brontë once said that her best friend Ellen Nussey lacked any sense of poetry in her life, but from this account and other writing of Ellen’s I would have to disagree. It is clear that Ellen loved the quiet, kind, brilliant Anne Brontë and mourned her loss, and we continue to do so today.

The loss of Anne Brontë in such untimely fashion was a huge blow to Charlotte Brontë, and she could little have known how remembered and revered her sister would be nearly two centuries after her death.

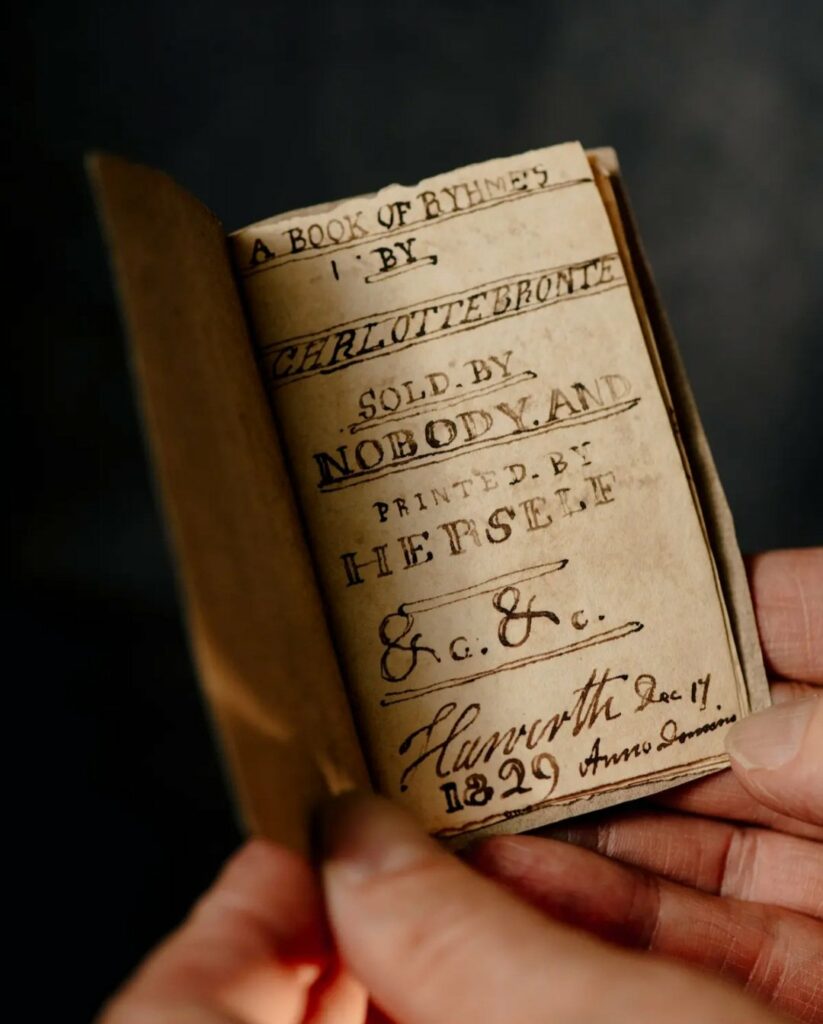

Anne Brontë changed my life; it was my decision to write a biography of Anne in 2015 that completely changed the direction of my life, and which has introduced me to so many wonderful people, through this blog and on my social media accounts, and in the ‘real’ world too. I know that Anne continues to touch, transform and improve other lives too through her wonderful writing which is as relevant and powerful today as it was when her quill first touched paper all those years ago.

Today we remember the late, great Anne Brontë but above all we say ‘thank you Anne’ for a life which was short but which was lived so courageously and to such great purpose. I hope you’ll join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.