March, as is befitting to its name, is marching on rapidly. This is a time of year when change is most visible. We can witness the year in a day; mornings begun with frost and ice merge into warm, sun filled days before a cold dusk descends once more. Above all others, perhaps, it is a liminal month, one betwixt and between the challenges of winter and the hope of spring.

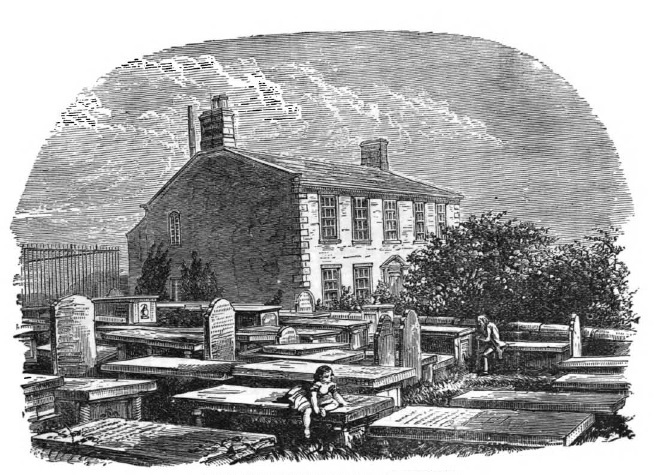

Living on the very border of nature, the Brontës saw this month of change in all its majesty enacted upon the moors which flowed from the parsonage on three sides. It was also apparent to them that this month often marks a change in people, in their circumstances, and these changes found their way into their brilliant books. In today’s new post we’re going to look at March in the novels of the Brontë sisters.

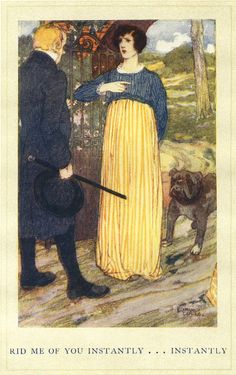

Jane Eyre

‘It had been a mild, serene spring day – one of those days which, towards the end of March or the beginning of April, rise shining over the earth as heralds of summer. It was drawing to an end now; but the evening was even warm, and I sat at work in the schoolroom with the window open.

“It gets late,” said Mrs. Fairfax, entering in rustling state. “I am glad I ordered dinner an hour after the time Mr. Rochester mentioned; for it is past six now. I have sent John down to the gates to see if there is anything on the road: one can see a long way from thence in the direction of Millcote.” She went to the window. “Here he is!” said she. “Well, John” (leaning out), “any news?”

“They’re coming, ma’am,” was the answer. “They’ll be here in ten minutes.”

Adèle flew to the window. I followed, taking care to stand on one side, so that, screened by the curtain, I could see without being seen.

The ten minutes John had given seemed very long, but at last wheels were heard; four equestrians galloped up the drive, and after them came two open carriages. Fluttering veils and waving plumes filled the vehicles; two of the cavaliers were young, dashing-looking gentlemen; the third was Mr. Rochester, on his black horse, Mesrour, Pilot bounding before him; at his side rode a lady, and he and she were the first of the party. Her purple riding-habit almost swept the ground, her veil streamed long on the breeze; mingling with its transparent folds, and gleaming through them, shone rich raven ringlets.

“Miss Ingram!” exclaimed Mrs. Fairfax, and away she hurried to her post below.’

Jane is now settled into life as a governess at Thornfield Hall, but this March day is bringing the first of two changes which will test her resilience to the limit. The arrival of Miss Ingram brings the first pang of jealousy to Jane’s heart, and perhaps the first realisation that she truly loves Rochester. The second change and challenge, of course, would come later on her supposed wedding day.

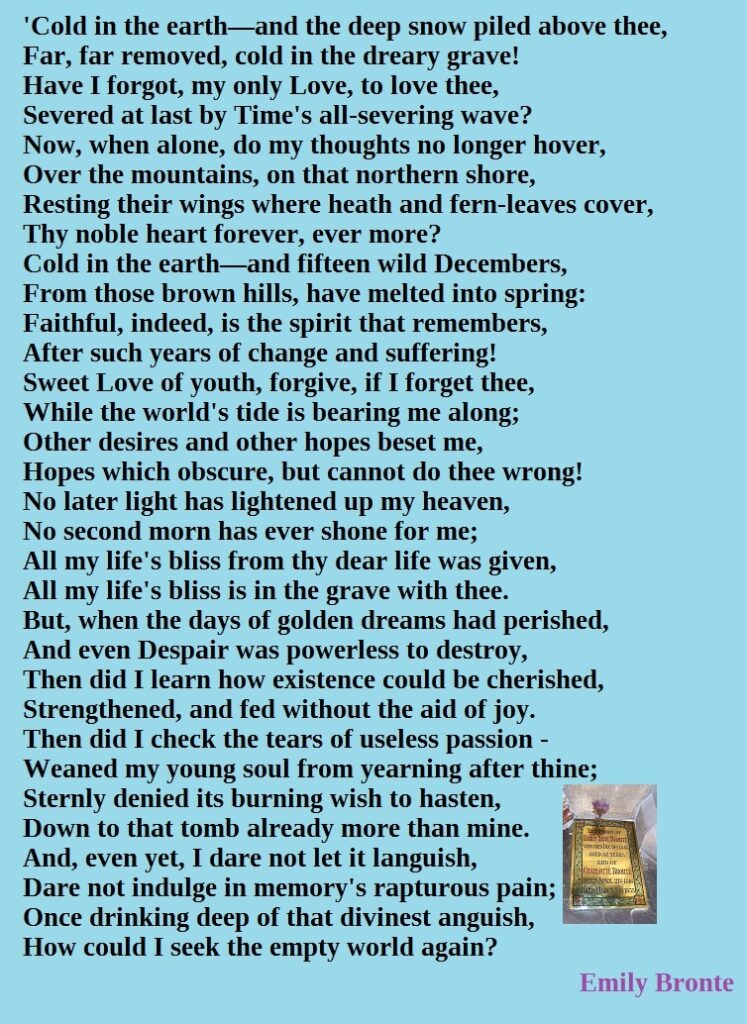

Wuthering Heights

‘Time wore on at the Grange in its former pleasant way till Miss Cathy reached sixteen. On the anniversary of her birth we never manifested any signs of rejoicing, because it was also the anniversary of my late mistress’s death. Her father invariably spent that day alone in the library; and walked, at dusk, as far as Gimmerton kirkyard, where he would frequently prolong his stay beyond midnight. Therefore Catherine was thrown on her own resources for amusement. This twentieth of March was a beautiful spring day, and when her father had retired, my young lady came down dressed for going out, and said she asked to have a ramble on the edge of the moor with me: Mr. Linton had given her leave, if we went only a short distance and were back within the hour.

“So make haste, Ellen!” she cried. “I know where I wish to go; where a colony of moor-game are settled: I want to see whether they have made their nests yet.”

“That must be a good distance up,” I answered; “they don’t breed on the edge of the moor.”

“No, it’s not,” she said. “I’ve gone very near with papa.”

I put on my bonnet and sallied out, thinking nothing more of the matter. She bounded before me, and returned to my side, and was off again like a young greyhound; and, at first, I found plenty of entertainment in listening to the larks singing far and near, and enjoying the sweet, warm sunshine; and watching her, my pet and my delight, with her golden ringlets flying loose behind, and her bright cheek, as soft and pure in its bloom as a wild rose, and her eyes radiant with cloudless pleasure. She was a happy creature, and an angel, in those days. It’s a pity she could not be content.

“Well,” said I, “where are your moor-game, Miss Cathy? We should be at them: the Grange park-fence is a great way off now.”

“Oh, a little further – only a little further, Ellen,” was her answer, continually. “Climb to that hillock, pass that bank, and by the time you reach the other side I shall have raised the birds.”

But there were so many hillocks and banks to climb and pass, that, at length, I began to be weary, and told her we must halt, and retrace our steps. I shouted to her, as she had outstripped me a long way; she either did not hear or did not regard, for she still sprang on, and I was compelled to follow. Finally, she dived into a hollow; and before I came in sight of her again, she was two miles nearer Wuthering Heights than her own home; and I beheld a couple of persons arrest her, one of whom I felt convinced was Mr. Heathcliff himself.’

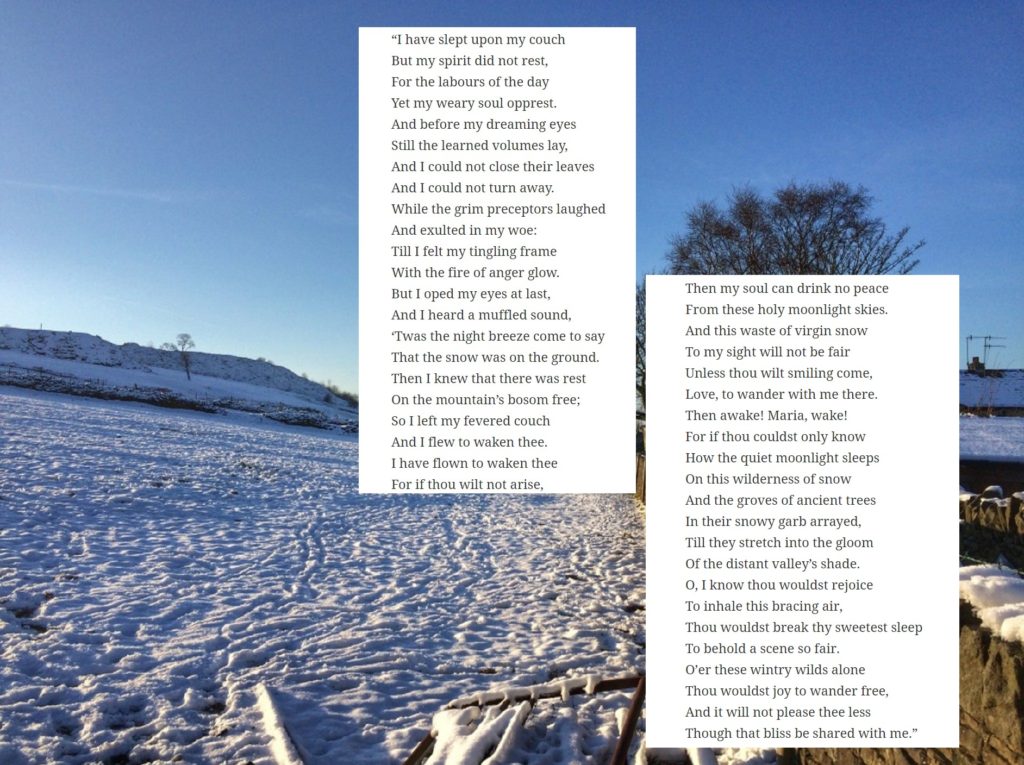

Emily Brontë chose today, the 20th of March, to mark the point at which young Cathy’s life would be changed forever. It is on this day that she meets Heathcliff, on this day that she is caught inevitably in his web of intrigue. This is the day at which her fate will be sealed and she will soon find herself a prisoner of Heathcliff and wife of his insipid son Linton. It’s surely no coincidence that Emily chose to name this specific date, the eve of the spring equinox when day and night are of equal strength, a time traditionally associated with change and a breaking with the past.

Agnes Grey

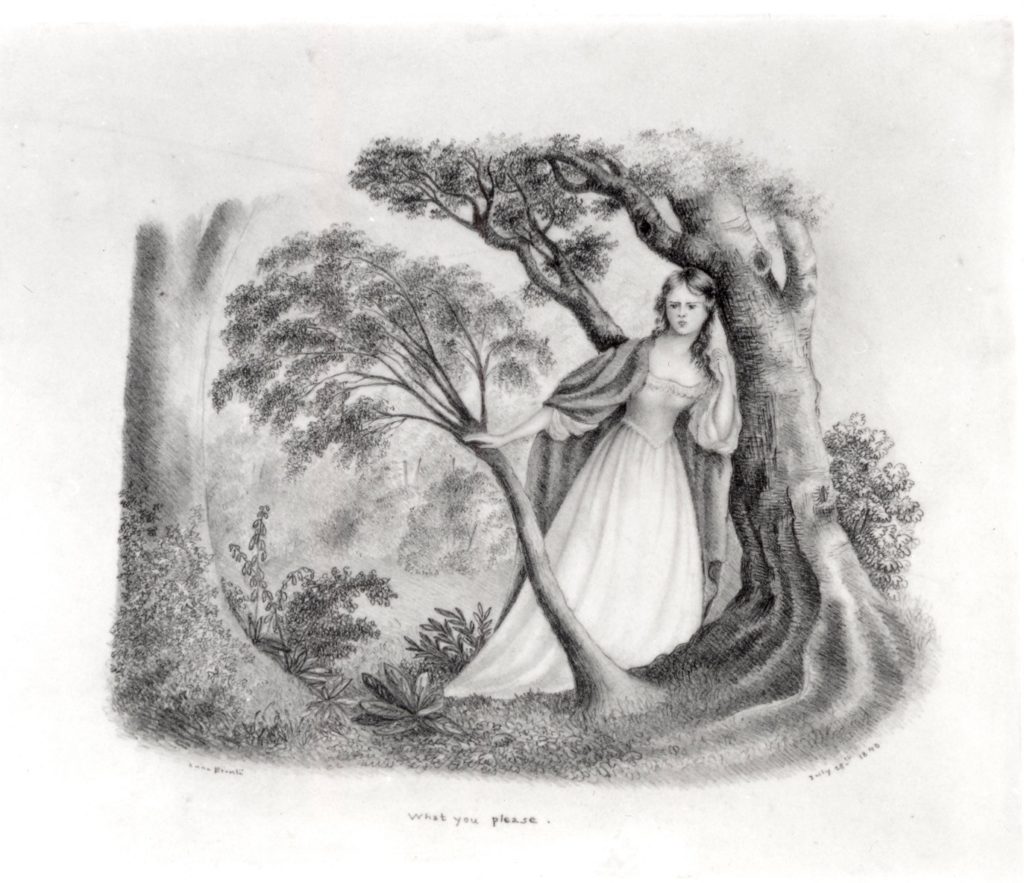

‘One such occasion I particularly well remember; it was a lovely afternoon about the close of March; Mr. Green and his sisters had sent their carriage back empty, in order to enjoy the bright sunshine and balmy air in a sociable walk home along with their visitors, Captain Somebody and Lieutenant Somebody-else (a couple of military fops), and the Misses Murray, who, of course, contrived to join them. Such a party was highly agreeable to Rosalie; but not finding it equally suitable to my taste, I presently fell back, and began to botanise and entomologise along the green banks and budding hedges, till the company was considerably in advance of me, and I could hear the sweet song of the happy lark; then my spirit of misanthropy began to melt away beneath the soft, pure air and genial sunshine; but sad thoughts of early childhood, and yearnings for departed joys, or for a brighter future lot, arose instead. As my eyes wandered over the steep banks covered with young grass and green-leaved plants, and surmounted by budding hedges, I longed intensely for some familiar flower that might recall the woody dales or green hill-sides of home: the brown moorlands, of course, were out of the question. Such a discovery would make my eyes gush out with water, no doubt; but that was one of my greatest enjoyments now. At length I descried, high up between the twisted roots of an oak, three lovely primroses, peeping so sweetly from their hiding-place that the tears already started at the sight; but they grew so high above me, that I tried in vain to gather one or two, to dream over and to carry with me: I could not reach them unless I climbed the bank, which I was deterred from doing by hearing a footstep at that moment behind me, and was, therefore, about to turn away, when I was startled by the words, “Allow me to gather them for you, Miss Grey,” spoken in the grave, low tones of a well-known voice. Immediately the flowers were gathered, and in my hand. It was Mr. Weston, of course—who else would trouble himself to do so much for me?

“I thanked him; whether warmly or coldly, I cannot tell: but certain I am that I did not express half the gratitude I felt. It was foolish, perhaps, to feel any gratitude at all; but it seemed to me, at that moment, as if this were a remarkable instance of his good-nature: an act of kindness, which I could not repay, but never should forget: so utterly unaccustomed was I to receive such civilities, so little prepared to expect them from anyone within fifty miles of Horton Lodge. Yet this did not prevent me from feeling a little uncomfortable in his presence; and I proceeded to follow my pupils at a much quicker pace than before; though, perhaps, if Mr. Weston had taken the hint, and let me pass without another word, I might have repeated it an hour after: but he did not. A somewhat rapid walk for me was but an ordinary pace for him.

“Your young ladies have left you alone,” said he.

“Yes, they are occupied with more agreeable company.”

“Then don’t trouble yourself to overtake them.” I slackened my pace; but next moment regretted having done so: my companion did not speak; and I had nothing in the world to say, and feared he might be in the same predicament. At length, however, he broke the pause by asking, with a certain quiet abruptness peculiar to himself, if I liked flowers.

“Yes; very much,” I answered, “wild-flowers especially.”

“I like wild-flowers,” said he; “others I don’t care about, because I have no particular associations connected with them—except one or two. What are your favourite flowers?”

“Primroses, bluebells, and heath-blossoms.”’

March for Agnes brings an encounter which utilises the symbolism of the month to the full. It shows the strengthening of the, as yet unacknowledged, love between Agnes and Weston and at the heart of this effortlessly romantic encounter is a love of wild flowers. For the Murray girls the things that matter most are society and riches, but the simple joys of nature are far greater treasures for the young governess and the assistant curate.

As so often in this novel, Anne Brontë uses the character of Agnes to express her own opinions and feelings. We know for certain that they both loved primroses and bluebells, for example, for in Anne’s poem ‘Memory’ she writes:

‘I closed my eyes against the day,

And called my willing soul away,

From earth, and air, and sky;

That I might simply fancy there

One little flower – a primrose fair,

Just opening into sight;

As in the days of infancy,

An opening primrose seemed to me

A source of strange delight.

Sweet Memory! ever smile on me;

Nature’s chief beauties spring from thee;

Oh, still thy tribute bring

Still make the golden crocus shine

Among the flowers the most divine,

The glory of the spring.

Still in the wallflower’s fragrance dwell;

And hover round the slight bluebell,

My childhood’s darling flower.’

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

‘“I suppose it is no use asking you to fix a day for your return?” said I.

“Why, no; I hardly can, under the circumstances; but be assured, love, I shall not be long away.”

“I don’t wish to keep you a prisoner at home,” I replied; “I should not grumble at your staying whole months away—if you can be happy so long without me – provided I knew you were safe; but I don’t like the idea of your being there among your friends, as you call them.”

“Pooh, pooh, you silly girl! Do you think I can’t take care of myself?”

“You didn’t last time. But THIS time, Arthur,” I added, earnestly, “show me that you can, and teach me that I need not fear to trust you!”

He promised fair, but in such a manner as we seek to soothe a child. And did he keep his promise? No; and henceforth I can never trust his word. Bitter, bitter confession! Tears blind me while I write. It was early in March that he went, and he did not return till July. This time he did not trouble himself to make excuses as before, and his letters were less frequent, and shorter and less affectionate, especially after the first few weeks: they came slower and slower, and more terse and careless every time. But still, when I omitted writing, he complained of my neglect. When I wrote sternly and coldly, as I confess I frequently did at the last, he blamed my harshness, and said it was enough to scare him from his home: when I tried mild persuasion, he was a little more gentle in his replies, and promised to return; but I had learnt, at last, to disregard his promises.’

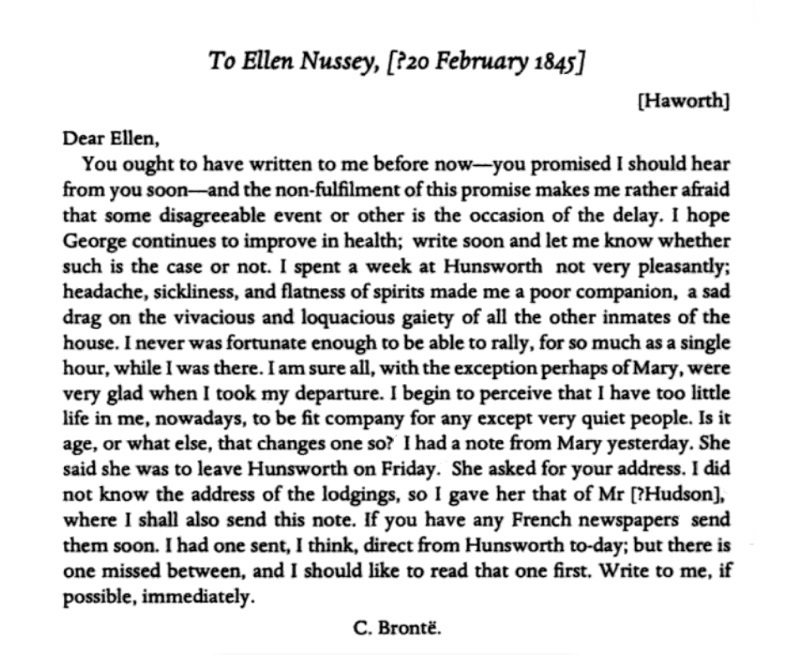

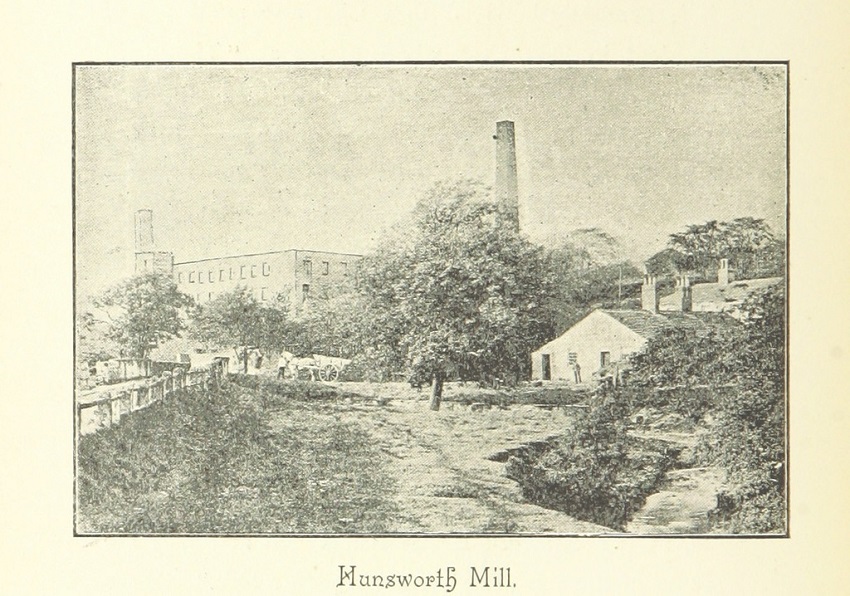

If March for Agnes Grey marked a time of hope springing forth, the month sees hope crushed for Helen Huntingdon. Arthur has strayed before, but it is this March exit that sees her trust and faith in her husband finally extinguished.

Villette

‘The next day was the first of March, and when I awoke, rose, and opened my curtain, I saw the risen sun struggling through fog. Above my head, above the house-tops, co-elevate almost with the clouds, I saw a solemn, orbed mass, dark blue and dim – THE DOME. While I looked, my inner self moved; my spirit shook its always-fettered wings half loose; I had a sudden feeling as if I, who never yet truly lived, were at last about to taste life. In that morning my soul grew as fast as Jonah’s gourd.

“I did well to come,” I said, proceeding to dress with speed and care. “I like the spirit of this great London which I feel around me. Who but a coward would pass his whole life in hamlets; and for ever abandon his faculties to the eating rust of obscurity?”

Being dressed, I went down; not travel-worn and exhausted, but tidy and refreshed. When the waiter came in with my breakfast, I managed to accost him sedately, yet cheerfully; we had ten minutes’ discourse, in the course of which we became usefully known to each other.

He was a grey-haired, elderly man; and, it seemed, had lived in his present place twenty years. Having ascertained this, I was sure he must remember my two uncles, Charles and Wilmot, who, fifteen, years ago, were frequent visitors here. I mentioned their names; he recalled them perfectly, and with respect. Having intimated my connection, my position in his eyes was henceforth clear, and on a right footing. He said I was like my uncle Charles: I suppose he spoke truth, because Mrs. Barrett was accustomed to say the same thing. A ready and obliging courtesy now replaced his former uncomfortably doubtful manner; henceforth I need no longer be at a loss for a civil answer to a sensible question.

The street on which my little sitting-room window looked was narrow, perfectly quiet, and not dirty: the few passengers were just such as one sees in provincial towns: here was nothing formidable; I felt sure I might venture out alone.

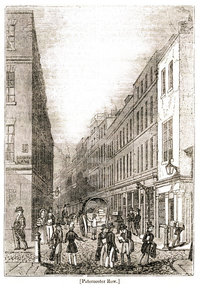

Having breakfasted, out I went. Elation and pleasure were in my heart: to walk alone in London seemed of itself an adventure. Presently I found myself in Paternoster Row – classic ground this. I entered a bookseller’s shop, kept by one Jones: I bought a little book – a piece of extravagance I could ill afford; but I thought I would one day give or send it to Mrs. Barrett. Mr. Jones, a dried-in man of business, stood behind his desk: he seemed one of the greatest, and I one of the happiest of beings.’

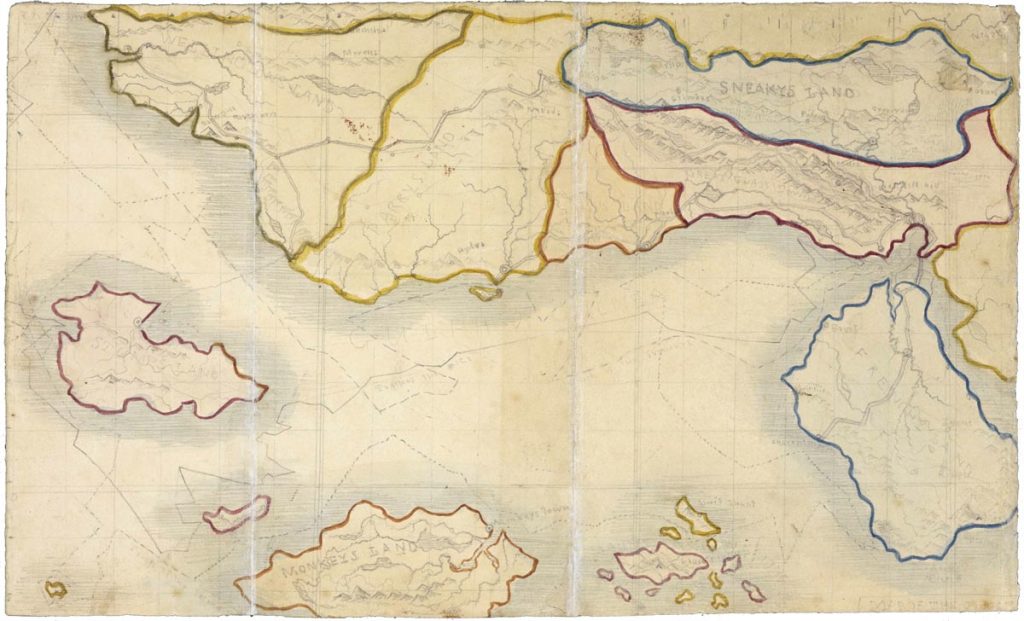

Just as March marks a turning point in the year, the start of a journey into spring and then summer, so too Lucy Snowe’s life takes on new life in this month. On the very first day she has left her old life behind and arrived in London, from whence she will travel to the Belgian city of Villette – in reality the Brussels which Charlotte Brontë knew so well.

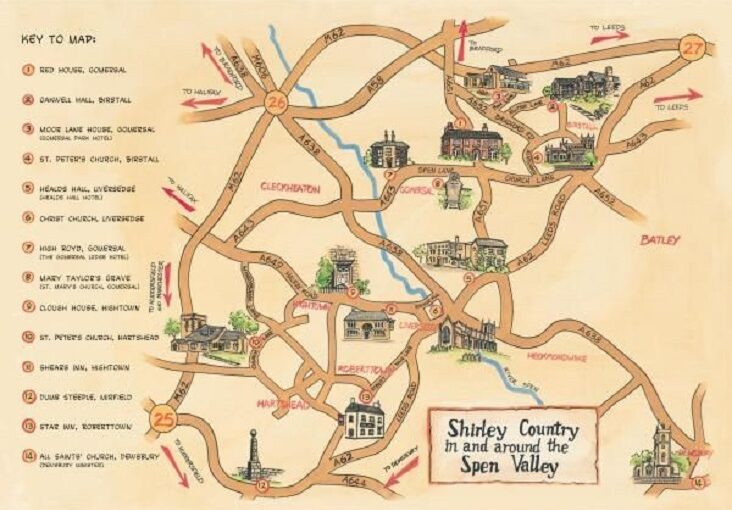

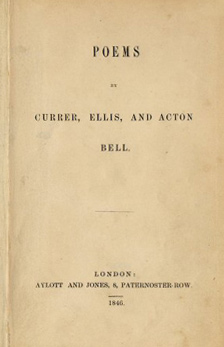

Lucy’s journey was well known to Charlotte, for it mirrors the one that she herself took in 1842. It is interesting too to see that Charlotte takes time to name one particular shop: the bookseller’s shop owned by Jones, the dried-in man of business. Perhaps this is an account of a very real person: Mr Jones of Aylott & Jones, the publisher of the first Brontë book Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell? Aylott & Jones were indeed based on Paternoster Row. This passage is a vital clue which indicates that Charlotte and Anne Brontë did visit this publisher during their fateful visit to London in 1848, even though it’s not mentioned in any of Charlotte’s letters.

We can sum up March in the Brontë novels in one word: change. The change of hope to despair and despair to hope, of loneliness to love. The Brontës knew that above all other months, March was the one which changed the year like no other. In the traditional saying it comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb, and the Latin for lamb is agnes. I hope that the progression of this month is suitably lamb-like for you all, there is a promise of sunnier, gentler times ahead. I must march on, but I will see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.