It’s a sunny Sunday so it’s time for another new Brontë blog post, and this could be the last of my Brontë blog posts on this WordPress platform – but we’ll come to that later. For now we’ll look at the early life of someone who was absolutely central to the Brontë story. Tomorrow, the 26th of June, is the 206th anniversary of his birth. Today we look at the early life of Branwell Brontë.

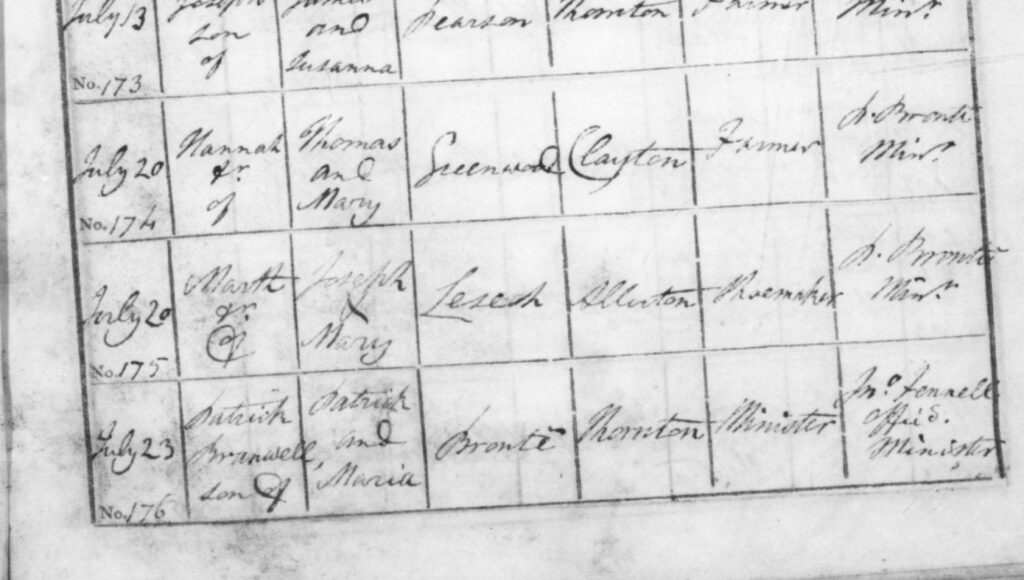

Branwell is the name we all know him by of course, but following the traditions of the time he was named after his father and given his mother’s maiden name as his middle name: Patrick Branwell Brontë. Perhaps to avoid confusion in the parsonage when his name was called out he was called Branwell by his family, but to the wider Haworth community he would have been Master Patrick, the rector’s son.

By the time of Branwell’s birth he had three elder sisters: Maria, Elizabeth and Charlotte. It was a patriarchal society he was born into so his parents, Patrick and Maria senior, must have been overjoyed that they now had a son. It would have been expected that he would grow up an educated and well-rounded man, one who might follow his father into the church, or perhaps enter business at a time of great opportunity in the area. It would also have been expected that he would marry and start a family of his own, and most importantly that he would care and provide for his sisters until they themselves found suitable husbands. None of this would come to pass.

We know of course that Branwell had plenty of demons to face in his adult life, and didn’t achieve what he may otherwise have done. At the time of his birth, and throughout his childhood, however he may still have been seen as the great hope of the Brontë family. We can get a glimpse of this if we fast-forward 31 years to the aftermath of his death, when a distraught Charlotte Brontë wrote (to W. S. Williams on 2nd October, 1848):

“My poor Father naturally thought more of his only son than of his daughters, and much and long as he had suffered on his account he cried out like David for that of Absalom – My Son! My Son! And refused at first to be comforted.”

In this same letter, Charlotte also recalls that: “Branwell was his Father’s and his sisters’ pride and hope in boyhood, but since Manhood, the case has been otherwise… I do not weep from a sense of bereavement – there is no prop withdrawn, no consolation torn away, no dear companion lost – but for the wreck of talent, the ruin of promise, the untimely dreary extinction of what might have been a burning and a shining light. My brother was a year my junior; I had aspirations and ambitions for him once – long ago.”

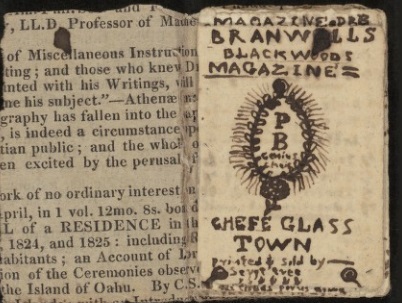

So we get here a glimpse of great sadness – perhaps not least on Charlotte’s part because in their childhood she and Branwell had been inseparable companions. In fact Branwell had been very close to all of his sisters in his early years (the picture at the head of this post depicts Branwell and his siblings in the Hollywood biopic ‘Devotion’). It was Branwell and Charlotte together who had first started writing, they who had conjured up the worlds of Glass Town and Angria from their imaginations and set them down in little books named “Branwell’s Blackwoods Magazine”. It was Branwell then who was the chief initial instigator of the very first Brontë writings. Charlotte and Branwell had been close and loving, but in his final years they were not on speaking terms, and Charlotte was left to deal with that enormous weight of guilt and grief after his passing.

There was clearly a lot of pressure on Branwell from an early age. He would have been left in no doubt that as the only son amongst six siblings (and it’s telling that Charlotte underlined the word ‘only’ in her letter) he would have been expected to be the only breadwinner. It seems clear, however, that despite the bravado and bluster he typically showed in later life he was a deeply sensitive individual. The loss of his mother when he was five and then the loss of his two elder siblings when he was seven must have impacted him deeply, and it is perhaps these early scars which had such an influence on his later life.

One other thing which would have greatly influenced Branwell’s early years was his schooling. Whilst his sisters were sent away to school (with tragic results in the case of Maria and Elizabeth), Branwell was schooled at home, by his father. One Haworth villager at least was less than impressed by that, as in an interview many years later Charles E. Hall recalled:

“He was a merry, well read, interesting boy , and it was not surprising that the men who gathered at the ‘Black Bull’ for liquor and entertainment enjoyed his gay company and made him welcome; nor was it surprising that he went there, considering that there was not a lad in the village, of his own social standing, with whom he could have consorted. It was a pity he was not sent away in early life, then all might have been different.”

Other Haworth villagers though were fulsome in their praise of young Branwell. In an 1868 interview one villager recalled: ‘“Oh, he was a fine talker Branwell; and such a talker! Ay, and when he was at the worst, he never missed coming to the Sunday school with his sisters”…

To his mind, Mr Branwell was the cleverest of the family. A wonderful talker he was, and able to do things which nobody he had ever seen could do. He had seen Branwell sitting in the vestry, talking to his (the sexton’s) father, and writing two different letters at the same time. He could take a pen in each hand, and write a letter with each at once. He had seen him do that many times, and had afterwards read the letters written in that way. Yes; it was true that he had come to a sad end, but Mrs Gaskell had not stated the case about him correctly.’

Nancy de Garrs, nurse to Branwell and his sisters, also remembered him fondly in an 1886 interview: ‘“Branwell was a good lad enough,” she says, “until the serpent beguiled him,” and she thinks he has been “made out to be a good deal worse than he really was.” Nancy could “manage him” better than any one else when his fits of fury were upon him, and Branwell seemed to have a real affection for his old nurse. He often wanted to paint her portrait, but she declined on the score that she did not consider herself good looking enough.’

Even so, we get a glimpse of the fits of fury which could possess him even in childhood. The same sudden anger which his great friend Francis Grundy witnessed from Branwell when they worked on the railway together: “He was proud of his name, his strength, and his abilities. In his fits of passion I have seen him drive his doubled fist through the panel of a door: it seemed to soothe him; it certainly bruised his knuckles.”

Grundy also was more than fulsome in his praise of Branwell, “Poor, brilliant, gay, moody, moping, wildly excitable, miserable Brontë!”

So what do we see of Branwell Brontë in his childhood and youth? He was a boy placed under intense pressure at an early age, and one that had to deal with intense tragedies at an early age. He was witty, kind and bright, able to write with two hands at once, and yet he could be prone to sudden bouts of anger, in his childhood he want bang his fists against walls, in adulthood he would turn to drink and drugs in an attempt to overpower the demons which besieged him.

We can never be certain when attaching modern medical terminology to people who lived in the past, but it seems likely to me that Branwell Brontë suffered from some form of mental illness, perhaps a bipolar disorder. In today’s world he may have got the help he needed, but there was no help for him in the nineteenth century. Grundy again perhaps sums it up well with his conclusion on Branwell Brontë: “Patrick Branwell Brontë was no domestic demon – he was just a man moving in a mist, who lost his way.”

In 1861, family friend William Dearden recalled what Branwell himself had said about his early days: ‘“Alas!” said he [Branwell Brontë] to me, many years after that sad event, “had I been what my father earnestly wished and strove to make me, I should not have been the wreck you see me now!”’

Talking of wrecks, to go off on a tangent, I’ve been having trouble with WordPress again – the system I use to host this website. For the second time in a matter of weeks the content of last week’s post was sent in an email to subscribers but did not show up at all on the web. Whether this post will show up or not I simply don’t know as I type this, and that’s obviously far from ideal. I therefore intend moving to a system called Substack for future posts.

What does this mean for readers? It simply means that the website will have rather a different appearance, but other than that all will be the same. There will still be free content weekly about Anne Brontë and her family, there will be no adverts, and hopefully I will be able to export my wonderful subscribers and all the archives on this site across as well. In my more than seven years of hosting this site on WordPress I’ve created over 400 posts containing well over half a million words, and I’ve still got lots more to say so I hope you can join me next week (whatever system I’m using) and on to a million words of Brontë blog posts and beyond!