This weekend marks the anniversary of a special event in the Brontë story which we have looked at before in previous years, but it’s such a special event that I had to mark it again in today’s new post. It is exactly 175 years ago to this weekend that Charlotte Brontë and Anne Brontë made the courageous decision to cast off their pen names, lower their masks and reveal their true identities to the world (or at least to Charlotte and Anne’s publisher).

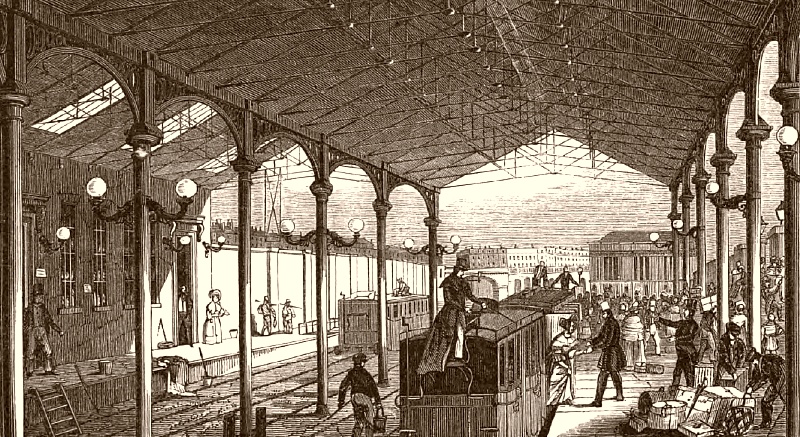

We have covered before the reason for the hurried journey Anne and Charlotte made on an overnight train that left Yorkshire on Friday 7th July and arrived in the early hours of Saturday 8th July 1848. A letter from Charlotte’s publisher had led them to believe that Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell (the pseudonyms they were using) were being accused of false dealings, an accusation that must be refuted however hard it may be for them and however much it may cost them.

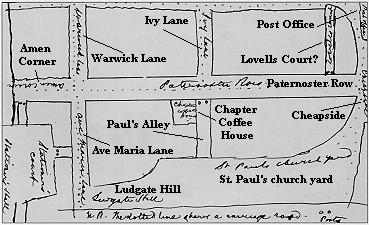

They checked into the Chapter Coffee House on Paternoster Row in the shadow of St. Paul’s Cathedral, and for an account of what happened next I will refer you to the following extract from the memoirs of Charlotte’s publisher, George Smith, himself:

“The works of Ellis and Acton Bell had been published by a Mr. Newby, on terms which rather depleted the scanty purses of the authors. When we were about to publish Shirley – the work which, in the summer of 1848, succeeded Jane Eyre – we endeavoured to make an arrangement with an American publisher to sell him advance sheets of the book, in order to give him an advantage in regard to time over other American publishers. There was, of course, no copyright with America in those days. We were met daring the negotiations with our American correspondents by the statement that Mr. Newby had informed them that he was about to publish the next book by the author of Jane Eyre under her other nom de plume of Acton Bell – Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell being in fact, according to him, one person. We wrote to ‘Currer Bell’ to say that we should be glad to be in a position to contradict the statement, adding at the same time we were quite sure Mr. Newby’s assertion was untrue. Charlotte Bronte has related how the letter affected her. She was persuaded that her honour was impugned. ‘With rapid decision’ says Mrs. Gaskell in her Life of Charlotte Bronte Charlotte and her sister Anne resolved that they should start for London that very day in order to prove their separate identity to Messrs. Smith, Elder, & Co.

With what haste and energy the sisters plunged into what was, for them, a serious expedition, how they reached London at eight o’clock on a Saturday morning, took lodgings in the Chapter coffee-house in Paternoster Row, and, after an agitated breakfast, set out on a pilgrimage to my office in Cornhill, is told at length in Mrs. Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë.

That particular Saturday morning I was at work in my room, when a clerk reported that two ladies wished to see me. I was very busy and sent out to ask their names. The clerk returned to say that the ladies declined to give their names, but wished to see me on a private matter. After a moment’s hesitation I told him to show them in. I was in the midst of my correspondence, and my thoughts were far away from ‘Currer Bell’ and Jane Eyre. Two rather quaintly dressed little ladies, pale-faced and anxious-looking, walked into my room; one of them came forward and presented me with a letter addressed, in my own handwriting, to ‘Currer Bell, Esq.’ I noticed that the letter had been opened, and said, with some sharpness, ‘Where did you get this from?’ ‘From the post-office’ was the reply; ‘it was addressed to me. We have both come that you might have ocular proof that there are at least two of us.’ This then was Currer Bell in person.

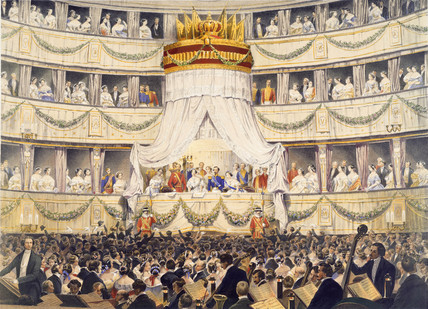

I need hardly say that I was at once keenly interested, not to say excited. Mr. Williams was called down and introduced, and I began to plan all sorts of attentions to our visitors. I tried to persuade them to come and stay at our house. This they positively declined to do, but they agreed that I should call with my sister and take them to the Opera in the evening. She has herself given

an account of her own and her sister Anne’s sensations on that occasion: how they dressed for the Opera in their plain, high-necked dresses: “fine ladies and gentlemen glanced at us, as we stood by

the box-door, which was not yet opened, with a slight graceful superciliousness, quite warranted by the circumstances. Still I felt pleasurably excited in spite of headache, sickness, and conscious clownishness; and I saw Anne was calm and gentle, which she always is. The performance was Rossini’s Barber of Seville – very brilliant, though I fancy there are things I should like better. We got home after one o’clock. We had never been in bed the night before; had been in constant excitement for twenty-four hours; you may imagine we were tired.”

My mother called upon them the next day. The sisters, after barely three days in London, returned to Haworth. In what condition of mind and body those few days left them is graphically told by Charlotte Bronte herself:

“On Tuesday morning we left London, laden with books Mr. Smith had given us, and got safely home. A more jaded wretch than I looked, it would be difficult to conceive. I was thin when I went, but I was meagre indeed when I returned, my face looking grey and very old, with strange deep lines ploughed in it – my eyes stared unnaturally. I was weak and yet restless.”

This is the only occasion on which I saw Anne Bronte. She was a gentle, quiet, rather subdued person, by no means pretty, yet of a pleasing appearance. Her manner was curiously expressive of a wish for protection and encouragement, a kind of constant appeal which invited sympathy.

I must confess that my first impression of Charlotte Bronte’s personal appearance was that it was interesting rather than attractive. She was very small, and had a quaint old-fashioned look. Her head seemed too large for her body. She had fine eyes, but her face was marred by the shape of the mouth and by the complexion.

There was but little feminine charm about her; and of this fact she herself was uneasily and perpetually conscious. It may seem strange that the possession of genius did not lift her above the weakness of an excessive anxiety about her personal appearance. But I believe that she would have given all her genius and her fame to have been beautiful. Perhaps few women ever existed more anxious to be pretty than she, or more angrily conscious of the circumstance that she was not pretty.”

We next turn to a fulsome account from Charlotte Brontë herself, given in a letter sent to her close friend Mary Taylor (or Polly as she was affectionately known):

“Dear Polly, I write you a great many more letters than you write me, though whether they all reach you, or not, Heaven knows! I dare say you will not be without a certain desire to know how our affairs get on; I will give you therefore a notion as briefly as may be. Acton Bell has published another book; it is in three volumes, but I do not like it quite so well as Agnes Grey the subject not being such as the author had pleasure in handling; it has been praised by some reviews and blamed by others. As yet, only 25 have been realised for the copyright, and as Acton Bell’s publisher is a shuffling scamp, I expected no more.

About two months since I had a letter from my publishers Smith and Elder saying that Jane Eyre had had a great run in America, and that a publisher there had consequently bid high for the first sheets of a new work by Currer Bell, which they had promised to let him have.

Presently after came another missive from Smith and Elder; their American correspondent had written to them complaining that the first sheets of a new work by Currer Bell had been already received, and not by their house, but by a rival publisher, and asking the meaning of such false play; it enclosed an extract from a letter from Mr. Newby (A. and C. Bell’s publisher) affirming that to the best of his belief Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (the new work) were all the production of one author.

This was a lie, as Newby had been told repeatedly that they were the production of three different authors, but the fact was he wanted to make a dishonest move in the game to make the public and the trade believe that he had got hold of Currer Bell, and thus cheat Smith and Elder by securing the American publisher’s bid.

The upshot of it was that on the very day I received Smith and Elder’s letter, Anne and I packed up a small box, sent it down to Keighley, set out ourselves after tea, walked through a snow-storm to the station, got to Leeds, and whirled up by the night train to London with the view of proving our separate identity to Smith and Elder, and confronting Newby with his lie.

We arrived at the Chapter Coffee House (our old place, Polly, we did not well know where else to go) about eight o’clock in the morning. We washed ourselves, had some breakfast, sat a few minutes, and then set off in queer inward excitement to 65 Cornhill. Neither Mr. Smith nor Mr. Williams knew we were corning, they had never seen us they did not know whether we were men or women, but had always written to us as men.

We found 65 to be a large bookseller’s shop, in a street almost as bustling as the Strand. We went in, walked up to the counter. There were a great many young men and lads here and there; I said to the first I could accost : ‘May I see Mr. Smith?’ He hesitated, looked a little surprised. We sat down and waited a while, looking at some books on the counter, publications of theirs well known to us, of many of which they had sent us copies as presents. At last we were shown up to Mr. Smith. ‘Is it Mr. Smith?’ I said, looking up through my spectacles at a tall young man. ‘It is.’ I then put his own letter into his hand directed to Currer Bell. He looked at it and then at me again. ‘Where did you get this?’ he said. I laughed at his perplexity a recognition took place. I gave my real name: Miss Brontë. We were in a small room ceiled with a great skylight and there explanations were rapidly gone into; Mr. Newby being anathematised, I fear, with undue vehemence. Mr. Smith hurried out and returned quickly with one whom he introduced as Mr. Williams, a pale, mild, stooping man of fifty, very much like a faded Tom Dixon. Another recognition and a long, nervous shaking of hands. Then followed talk talk talk; Mr. Williams being silent, Mr. Smith loquacious.

Mr. Smith said we must come and stay at his house, but we were not prepared for a long stay and declined this also; as we took our leave he told us he should bring his sisters to call on us that evening. We returned to our inn, and I paid for the excitement of the interview by a thundering headache and harassing sickness. Towards evening, as I got no better and expected the Smiths to call, I took a strong dose of sal volatile. It roused me a little; still, I was in grievous bodily case when they were announced. They came in, two elegant young ladies, in full dress, prepared for the Opera Mr. Smith himself in evening costume, white gloves, etc. We had by no means understood that it was settled we were to go to the Opera, and were not ready. Moreover, we had no fine, elegant dresses with us, or in the world. However, on brief rumination I thought it would be wise to make no objections. I put my headache in my pocket, we attired ourselves in the plain, high-made country garments we possessed, and went with them to their carriage, where we found Mr. Williams. They must have thought us queer, quizzical-looking beings, especially me with my spectacles. I smiled inwardly at the contrast, which must have been apparent, between me and Mr. Smith as I walked with him up the crimson-carpeted staircase of the Opera House and stood amongst a brilliant throng at the box door, which was not yet open. Fine ladies and gentlemen glanced at us with a slight, graceful superciliousness quite warranted by the circumstances. Still, I felt pleasantly excited in spite of headache and sickness and conscious clownishness, and I saw Anne was calm and gentle, which she always is.

The performance was Rossini’s opera of the Barber of Seville, very brilliant, though I fancy there are things I should like better. We got home after one o’clock; we had never been in bed the night before, and had been in constant excitement for twenty-four hours. You may imagine we were tired.

The next day, Sunday, Mr. Williams came early and took us to church. He was so quiet, but so sincere in his attentions, one could not but have a most friendly leaning towards him. He has a nervous hesitation in speech, and a difficulty in finding appropriate language in which to express himself, which throws him into the background in conversation; but I had been his correspondent and therefore knew with what intelligence he could write, so that I was not in danger of undervaluing him. In the afternoon Mr. Smith came in his carriage with his mother, to take us to his house to dine. Mr. Smith’s residence is at Bayswater, six miles from Cornhill; the rooms, the drawing-room especially, looked splendid to us. There was no company only his mother, his two grown-up sisters, and his brother, a lad of twelve or thirteen, and a little sister, the youngest of the family, very like himself. They are all dark-eyed, dark-haired, and have clear, pale faces. The mother is a portly, handsome woman of her age, and all the children more or less well-looking one of the daughters decidedly pretty. We had a fine dinner, which neither Anne nor I had appetite to eat, and were glad when it was over. I always feel under an awkward constraint at table. Dining out would be hideous to me.

Mr. Smith made himself very pleasant. He is a practical man, I wish Mr. Williams were more so, but he is altogether of the contemplative, theorising order. Mr. Williams has too many abstractions.

On Monday we went to the Exhibition of the Royal Academy and the National Gallery, dined again at Mr. Smith’s, then went home with Mr. Williams to tea and saw his comparatively humble but neat residence and his fine family of eight children. A daughter of Leigh Hunt’s was there. She sang some little Italian airs which she had picked up among the peasantry in Tuscany, in a manner that charmed me.

On Tuesday morning we left London laden with books which Mr. Smith had given us, and got safely home, A more jaded wretch than I looked when I returned it would be difficult to conceive. I was thin when I went, but was meagre indeed when I returned; my face looked grey and very old, with strange, deep lines ploughed in it; my eyes stared unnaturally. I was weak and yet restless. In a while, however, the bad effects of excitement went off and I regained my normal condition. We saw Mr. Newby, but of him more another time. Good-bye. God bless you. Write. C B.”

So there we have two accounts from two of the three protagonists, unfortunately Anne Brontë did not leave her account, of an event that changed world literature forever. Without that letter from Thomas Cautley Newby, a confidence trickster as much as a publisher, Charlotte and Anne Brontë would never have gone to London – perhaps we would never have known their real names. But that letter started a chain of events which leads to today where the Brontë novels are loved, and the Brontës themselves are loved.

There is probably a darker side to this trip too. Charlotte talks of fatigue and depression of spirits, something she constantly battled. She also suddenly looks grey and very old, she is weak and restless. Within a year of their return to Haworth, a terrible tragedy had decimated Haworth Parsonage. Branwell, Emily and Anne Brontë had all died of tuberculosis, but it was not one of the main causes of death in rural Haworth, it was a disease of the big city. It seems likely that either Charlotte or Anne caught it in the crowds of London and brought it back to the parsonage with them. The rest, sadly, is history.

I hope to see you here (or on the new site when it is finally up and running, but the address will be the same) for another Brontë blog post next week.