The Brontë sisters Anne, Emily and Charlotte were brilliant writers, as we and the world know of course. They were also fine artists too, and their chosen subjects were often the world they saw around them, from family pets to the flora and fauna they encountered around their home and on the moors. We know that this week marks the anniversary of the production of an exquisite sketch made by a young Charlotte Brontë so we shall look at that in today’s post, and the clue it gives us about the great novel Jane Eyre.

Firstly, however, let’s not forget the beautiful artwork of Anne Brontë. Above is her ‘Sunrise Over Sea’. We know that Anne developed a deep love of the sea, and is buried in Scarborough overlooking it, but at the time she created this prophetic picture she had never seen the sea.

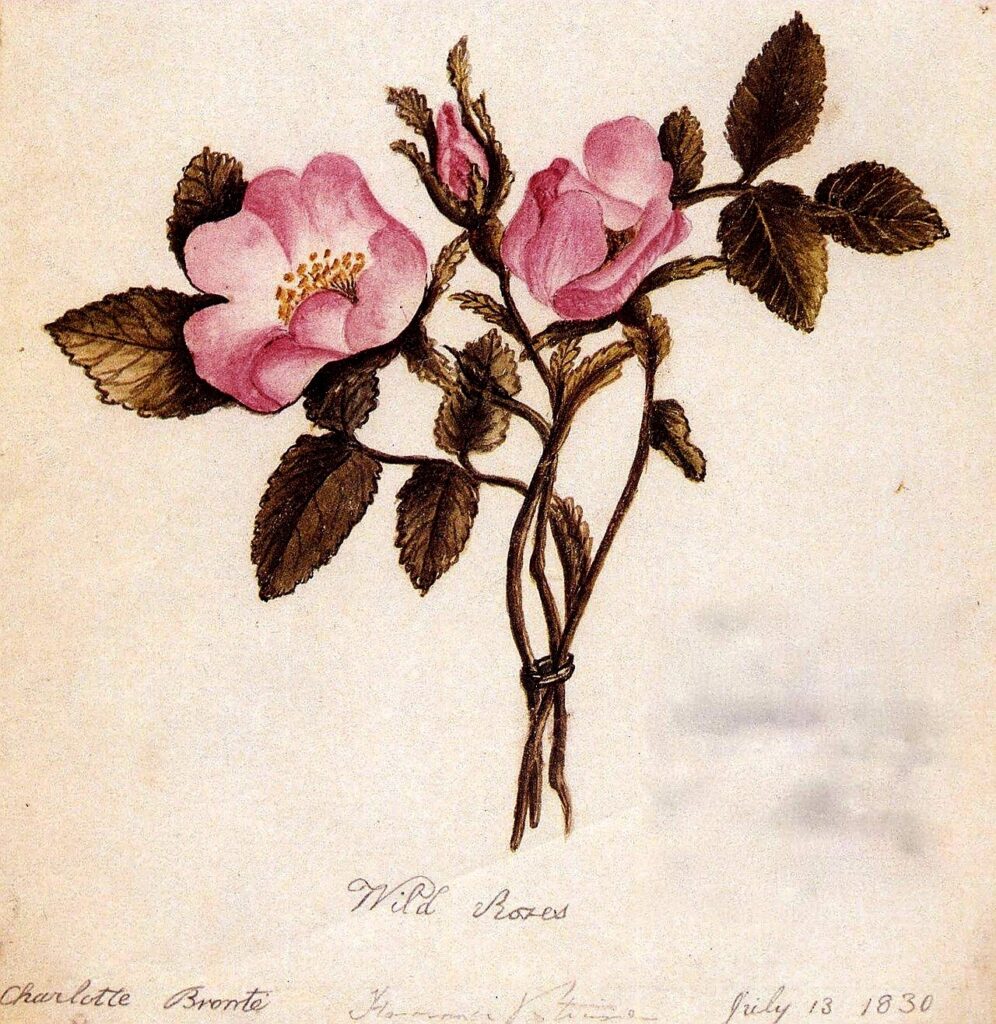

Now let’s return to Charlotte’s picture, one helpfully dated by her so that we know it was painted on 13th July 1830, when she was just 14 years old.

Charlotte was obviously a painting prodigy, and whilst some of her early art would have been copied from text books or during art lessons we know, from the title she has given this composition, that these were ‘wild roses, from nature’.

Amidst the Brontë Parsonage Museum collection are many such paintings by Charlotte of flowers and plants, from convolvulus to ferns and primroses. All are colourful, highly detailed and exquisitely elegant. Here obviously was a woman in love with nature, and in love with painting. Seventeen years after Charlotte sat with her painting kit before a wild rose, the world would be introduced to another young woman who loved painting: Jane Eyre.

As a governess, a role which both Charlotte and Anne had occupied and which they in turn gave to their heroines Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey, Jane would have been expected to be able to paint. It was adjudged a feminine art, a pleasant way for women in society to pass their time, although of course there could be no question of them painting seriously or expecting to make money from it (as another of Anne Brontë’s heroines, Helen the titular tenant of Wildfell Hall, does in a further signal of her break from society’s conventions).

A governess would need to be able to paint to some degree so that she could teach her charges how to paint, but they would not have been expected to excel at it. And yet Charlotte and Anne Brontë did excel at painting, as did Jane Eyre.

In the novel bearing her name, Jane is such an accomplished artist that not only does she teach her pupil Adele to draw, her own compositions catch the eye of Rochester – as we see in the following extract:

‘Mr. Rochester continued –

“Adèle showed me some sketches this morning, which she said were yours. I don’t know whether they were entirely of your doing; probably a master aided you?”

“No, indeed!” I interjected.

“Ah! that pricks pride. Well, fetch me your portfolio, if you can vouch for its contents being original; but don’t pass your word unless you are certain: I can recognise patchwork.”

“Then I will say nothing, and you shall judge for yourself, sir.”

I brought the portfolio from the library.

“Approach the table,” said he; and I wheeled it to his couch. Adèle and Mrs. Fairfax drew near to see the pictures.

“No crowding,” said Mr. Rochester: “take the drawings from my hand as I finish with them; but don’t push your faces up to mine.”

He deliberately scrutinised each sketch and painting. Three he laid aside; the others, when he had examined them, he swept from him.

“Take them off to the other table, Mrs. Fairfax,” said he, “and look at them with Adèle;—you” (glancing at me) “resume your seat, and answer my questions. I perceive those pictures were done by one hand: was that hand yours?”

“Yes.”

“And when did you find time to do them? They have taken much time, and some thought.”

“I did them in the last two vacations I spent at Lowood, when I had no other occupation.”

“Where did you get your copies?”

“Out of my head.”

“That head I see now on your shoulders?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Has it other furniture of the same kind within?”

“I should think it may have: I should hope – better.”

He spread the pictures before him, and again surveyed them alternately.

While he is so occupied, I will tell you, reader, what they are: and first, I must premise that they are nothing wonderful. The subjects had, indeed, risen vividly on my mind. As I saw them with the spiritual eye, before I attempted to embody them, they were striking; but my hand would not second my fancy, and in each case it had wrought out but a pale portrait of the thing I had conceived.

These pictures were in water-colours. The first represented clouds low and livid, rolling over a swollen sea: all the distance was in eclipse; so, too, was the foreground; or rather, the nearest billows, for there was no land. One gleam of light lifted into relief a half-submerged mast, on which sat a cormorant, dark and large, with wings flecked with foam; its beak held a gold bracelet set with gems, that I had touched with as brilliant tints as my palette could yield, and as glittering distinctness as my pencil could impart. Sinking below the bird and mast, a drowned corpse glanced through the green water; a fair arm was the only limb clearly visible, whence the bracelet had been washed or torn.

The second picture contained for foreground only the dim peak of a hill, with grass and some leaves slanting as if by a breeze. Beyond and above spread an expanse of sky, dark blue as at twilight: rising into the sky was a woman’s shape to the bust, portrayed in tints as dusk and soft as I could combine. The dim forehead was crowned with a star; the lineaments below were seen as through the suffusion of vapour; the eyes shone dark and wild; the hair streamed shadowy, like a beamless cloud torn by storm or by electric travail. On the neck lay a pale reflection like moonlight; the same faint lustre touched the train of thin clouds from which rose and bowed this vision of the Evening Star.

The third showed the pinnacle of an iceberg piercing a polar winter sky: a muster of northern lights reared their dim lances, close serried, along the horizon. Throwing these into distance, rose, in the foreground, a head,—a colossal head, inclined towards the iceberg, and resting against it. Two thin hands, joined under the forehead, and supporting it, drew up before the lower features a sable veil; a brow quite bloodless, white as bone, and an eye hollow and fixed, blank of meaning but for the glassiness of despair, alone were visible. Above the temples, amidst wreathed turban folds of black drapery, vague in its character and consistency as cloud, gleamed a ring of white flame, gemmed with sparkles of a more lurid tinge. This pale crescent was “the likeness of a kingly crown;” what it diademed was “the shape which shape had none.”

“Were you happy when you painted these pictures?” asked Mr. Rochester presently.

“I was absorbed, sir: yes, and I was happy. To paint them, in short, was to enjoy one of the keenest pleasures I have ever known.”

“That is not saying much. Your pleasures, by your own account, have been few; but I daresay you did exist in a kind of artist’s dreamland while you blent and arranged these strange tints. Did you sit at them long each day?”

“I had nothing else to do, because it was the vacation, and I sat at them from morning till noon, and from noon till night: the length of the midsummer days favoured my inclination to apply.”

“And you felt self-satisfied with the result of your ardent labours?”

“Far from it. I was tormented by the contrast between my idea and my handiwork: in each case I had imagined something which I was quite powerless to realise.”

“Not quite: you have secured the shadow of your thought; but no more, probably. You had not enough of the artist’s skill and science to give it full being: yet the drawings are, for a school-girl, peculiar. As to the thoughts, they are elfish. These eyes in the Evening Star you must have seen in a dream. How could you make them look so clear, and yet not at all brilliant? for the planet above quells their rays. And what meaning is that in their solemn depth? And who taught you to paint wind? There is a high gale in that sky, and on this hill-top. Where did you see Latmos? For that is Latmos. There! put the drawings away!”’

The first picture which impresses Rochester is a cormorant. It’s surely a coincidence that Charlotte Brontë herself had also drawn a cormorant, featured below:

It’s no coincidence at all, of course. Like all of the Brontë novels with the exception of Wuthering Heights, which has some historical influences upon its tale of a bitter generational feud, Jane Eyre has autobiographical elements to it. The author, Charlotte Brontë as we know but which was unknown to the reading public upon its release, even gave her novel the subtitle,”An Autobiography”.

This painting scene is one clue that Jane, on the face of it quiet and diminutive but at heart feisty, determined and passionate, is based at least in part upon Charlotte Brontë. We can also be sure that Rochester, at first cold, haughty and brutish, is based upon Monsieur Heger, the masterful Belgian tutor who can be found in all of Charlotte’s heroes. Perhaps this scene with paintings cast aside but others subjected to faint praise which meant everything to the painter, was drawn from real life over a desk in Brussels?

Jane Eyre works brilliantly as a novel even to people who know nothing of its creator, which is why it was such a phenomenal success upon its release in 1847 and remains so today, but it can be even more entertaining when we realise how much of it reflects the life and feelings of its author.

I hope to see you next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post, when we’ll continue to paint a picture of this fascinating family.