1855 was a year of sorrow in Haworth, and especially in and around Haworth Parsonage. In February of that year, long standing servant of the Brontë family Tabby Aykroyd died, and a month and a half later the great Charlotte Brontë died whilst pregnant, bringing hopes of a continuation of the family line to an end. On this day in 1855 parish sexton and Brontë neighbour John Brown was buried, and in today’s post we take a look at his role in the Brontë story.

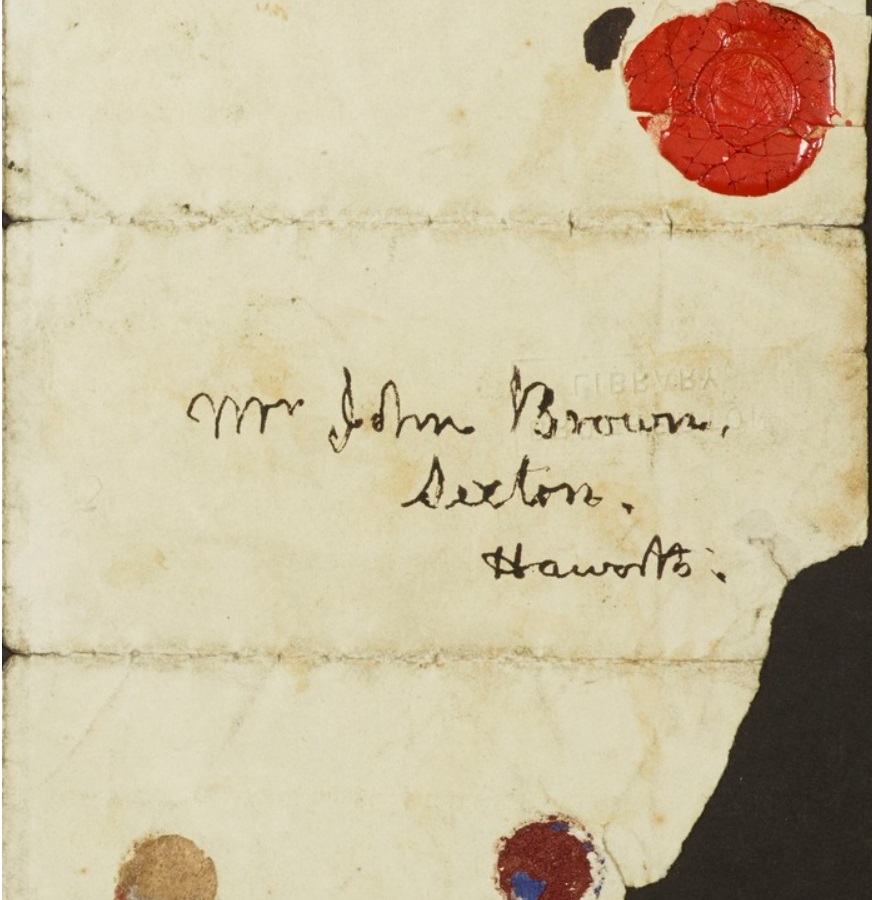

Born in 1804, John Brown came from a long line of sextons and stonemasons and he continued the family tradition, becoming sexton of St. Michael’s and All Angels church in Haworth. It was an important role in the parish, as he was responsible for creating the stone monuments in Haworth’s churchyard, as well as maintaining the graveyard and church itself. In a parish such as Haworth, where annual epidemics decimated the population, it was also a very busy occupation.

As sexton, Brown had to work very closely with the parish priest, and so the Brown family occupied a house in close proximity to the parsonage. If you walk to the Brontë Parsonage today you will pass Sexton House on the alleyway leading up to it, just prior to the old schoolhouse. In fact it was John Brown himself who built this house in 1832, when he was just 28 years old.

John Brown was clearly a very respected man in the village, for he was Master of its Three Graces masonic lodge – a position of honour. When Patrick Brontë were looking for a new servant for the parsonage in 1839 it was to John Brown that he turned – and his young daughter Martha made the short walk from Sexton House to the Parsonage to become the new live in servant, a role she would occupy until Patrick’s passing in 1861.

John Brown was clearly a hard working and well respected man, and he was a family man too, for he and his wife Mary had (just as Patrick and Maria Brontë had) six children. In John Brown’s case, all his children were daughters.

Thanks to his role and his proximity, John Brown would have become very well known to the Brontë family, but there was one member particularly that he became close to: Branwell Brontë. So close were they that John Brown secured Branwell a position within the Three Graces lodge even before he was old enough to officially be a Freemason. We also know that they were regular drinking partners, but Brown must have been more temperate in his habits than his friend, for in 1845 it was he who was entrusted to take Branwell to Liverpool in an attempt to take him away from his habitual drinking in Haworth. This was referred to by Anne Brontë in her diary paper of 31st July 1855:

“Branwell has left Luddendenfoot and been a Tutor at Thorp Green and had much tribulation and ill health. He was very ill on Tuesday but he went with John Brown to Liverpool where he now is I suppose, and we hope he will be better and do better in future.”

Anne continues in this diary paper to say “This is a dismal cloudy wet evening. We have had so far a very cold wet summer.” Tell us about it Anne!

Charlotte Brontë also refers to this trip in a letter she sent to Ellen Nussey on the same day that Anne was writing her diary paper: “It was ten o’ clock at night when I got home – I found Branwell ill – he is so very often owing to his own fault – I was not therefore shocked at first – but when Anne informed me of the immediate concern of his present illness I was greatly shocked. He had last Thursday received a note from Mr Robinson sternly dismissing him intimating that he had discovered his proceedings which he characterised as bad beyond expression and charging him on pain of exposure to break off instantly and for ever all communication with every member of his family. We have had sad work with Branwell since – he thought of nothing but stunning or drowsing his distress of mind – no one in the house could have rest – and at last we have been obliged to send him from home for a week with some one to look after him.”

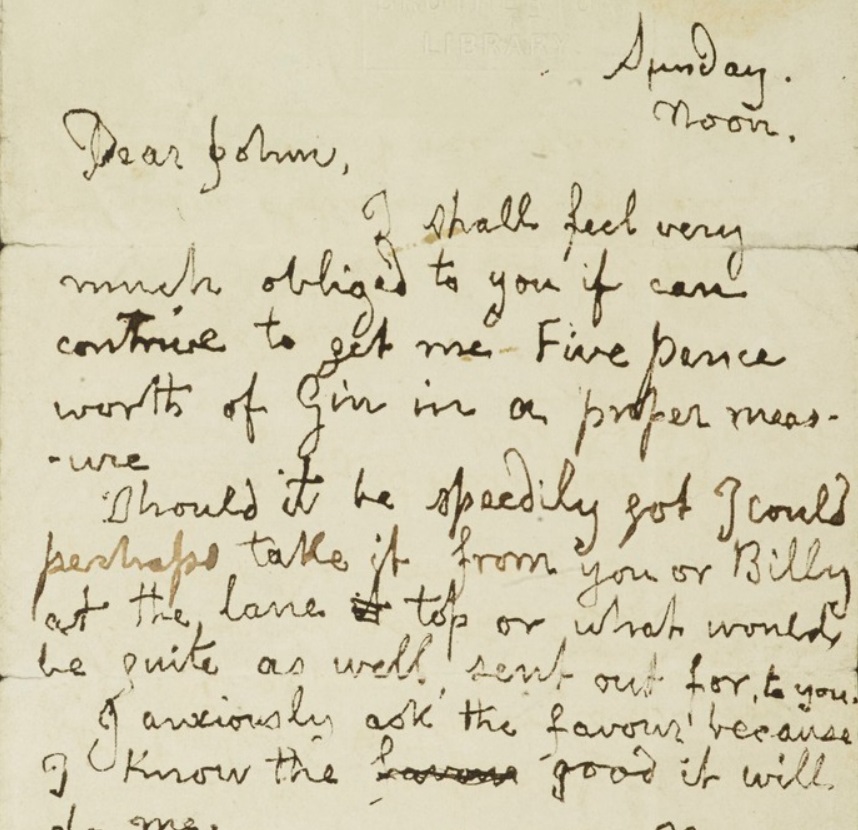

How the week in Liverpool passed we do not know, other than that they took a steamer boat trip together along the Welsh coast from where Branwell drew Penmaenmawr mountain, but Brown was unable to curb Branwell’s excesses. Towards the end of Branwell’s life, when he was too ill to leave the house, he would write to Brown begging him to lend him money and send him drink.

As Brown’s daughters left, like Martha, to take up positions elsewhere, Sexton House became a regular boarding house for Patrick Brontë’s assistant curates. One who stayed there was Arthur Bell Nicholls. They may have got on well initially, Arthur too was well liked in the village, but Arthur’s disastrous proposal to Charlotte Brontë at the close of 1852 saw John Brown take a furious dislike to the man. How dare this man, a mere assistant curate from Ireland, think he was worthy to marry Charlotte Brontë? On 2nd January 1853 Charlotte wrote to Ellen Nussey:

“I am sorry for one other person [Arthur] whom nobody pities but me. Martha is bitter against him: John Brown says he should like to shoot him.”

We know of course that in 1854 Charlotte and Arthur married. Martha’s bitterness had vanished for she and Arthur became great friends, so much so that she later left Haworth and went to live in Ireland with Arthur and his second wife. John Brown too must have buried the hatchet, for we know that he was instrumental in organising the wedding ceremony. We know this thanks to an amazing account given in later life by James Robinson, who as a teenage apprentice teacher back in 1854 was one of only a handful of people to witness the early morning ceremony that saw Charlotte and Arthur united. Thanks to his account we also get a first hand account of John Brown and how he spoke:

“They were married during my apprenticeship. It was not known in the neighbourhood that the marriage was coming off, and to my surprise, when going past the end of ‘Church Fields’ to my lessons one morning, old John Brown, the sexton, was waiting for me, and said: ‘We want tha to go to t’top of t’ ‘ill to watch for three parsons coming from t’other hill, coming from Oxenhope. Charlotte and Mr. Nicholls are going to be married, and when tha sees Mr. Nicholls, Mr. Grant, and Mr. Sowden coming at t’ far hill, tha must get back to t’ Parsonage, so’s Charlotte and Ellen Nussey can get their things on to go down to t’ church.’”

When John Brown died just a year later, the cause of death was given as ‘dust on the lungs’. This was no doubt a result of his years making and carving gravestones. Now his own memorial lies just outside the garden wall of Haworth Parsonage.

On the day of his funeral, exactly 168 years ago today, we know that Patrick Brontë sat in the front pews, normally reserved for the Brontë family, alongside Mary Brown and Martha Brown. Poor Martha who in the space of a few months had lost the woman, Tabby, who had been alongside her all her working life, Charlotte, who had become a great friend, and finally her father John. Presiding over the funeral service was the man John had threatened to shoot less than three years earlier, Arthur Bell Nicholls.

John Brown was friend to the Brontës and to the village of Haworth as a whole. When we look at Sexton House today, or at the vast array of monuments in Haworth’s churchyard, let us remember the man responsible for them. A man at the heart of the Brontë’s daily lives, at the heart of the Brontë story.

Let me finish by apologising for last week’s blog no show. Once again, the WordPress blogging platform defeated me, but a move to a new platform is imminent. I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.