In previous posts we have looked at the infamous letter that poet laureate Robert Southey sent to Charlotte Brontë in 1837, when she was just 20 years old, and at Charlotte’s response and a further reply from Southey. In short, the celebrated poet was telling Charlotte that poetry and literary creation could not and should not be a woman’s work. We know that Charlotte valued that advice highly at the time, but surely after she found success as a writer she looked upon it in a different light. Or did she? A letter sent on this weekend in 1850 gives us a clue to her thoughts, and to her initial 1837 letter which is now lost, so that’s what we will look at in today’s post.

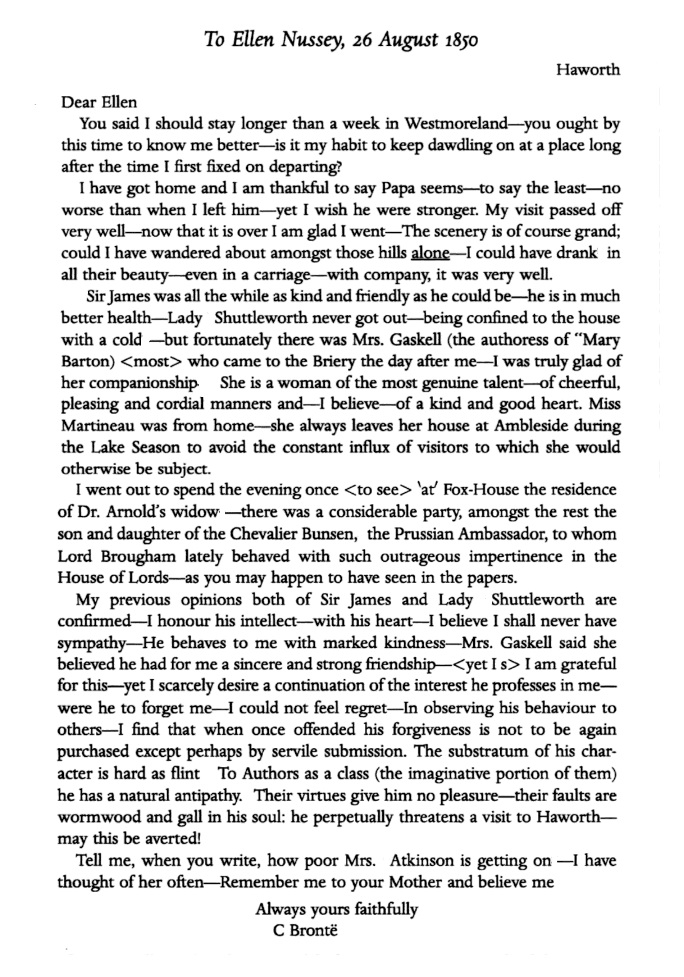

The letter arrived during a momentous week for Charlotte Brontë, for she was staying at Briery Close near Lake Windermere at the time (that’s it, at the head of this post). This was the home or Sir James and Lady Kay-Shuttleworth, great admirers of Charlotte who regularly courted Charlotte’s company, often to her displeasure. As this letter sent to Ellen Nussey on 26th August 1850 shows, the day after her return, whilst at Briery Close she met Matthew Arnold, the family of the Prussian ambassador, and a certain someone whose name would become forever associated with her own: this was the first meeting between Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell:

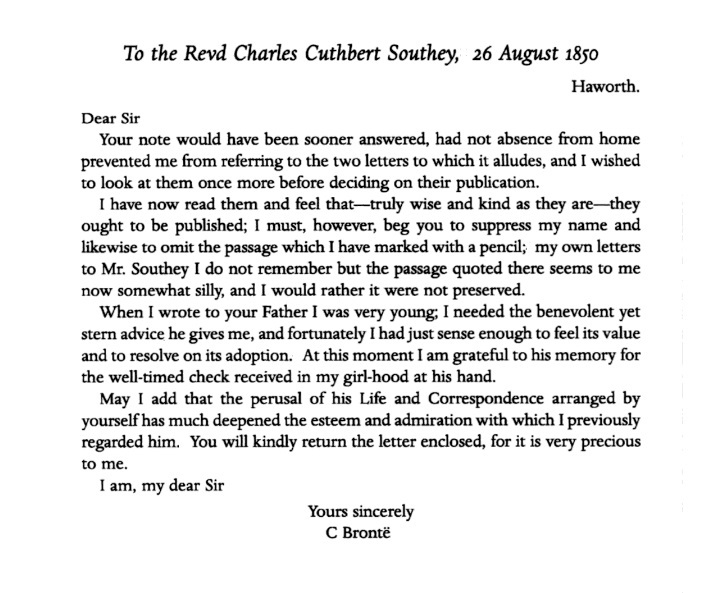

Whilst at the Lake District, Charlotte also received a letter from the Reverend Cuthbert Southey. He was the sole surviving son of Robert Southey, and was busily at work on a biography of his father. During the course of his research he had come across details of the between Charlotte and Southey and had contacted Miss Brontë asking if she would supply him with the letters in question. Charlotte sent her response upon her return to Haworth, when she’d had a chance to retrieve the letters, and so I produce Charlotte’s reply, once again sent on 26th August 1850 below:

This is a very interesting letter, for it shows that more than 13 years after receiving Robert Southey’s letter, and despite by then being a hugely successful writer herself, she still valued Southey’s advice and the memory of its author. She ‘needed the needed the benevolent and stern advice he gives me’, she wrote, but many would disagree.

Cuthbert’s memoir of his father gives us a tantalising glimpse of the initial letter that Charlotte Brontë sent to him, especially in the passage that Charlotte marked for deletion from Cuthbert’s book. The passage, written by Robert Southey but containing quotes from Charlotte, is as follows:

‘What I am, you might have learnt by such of my publications as have come into your hands: but you live in a visionary world; & seem to imagine that this is my case also, when you speak of my “stooping from a throne of light & glory”. Had you happened to be acquainted with me, a little personal knowledge would have tempered your enthusiasm. You who so ardently desire “to be forever known” as a poetess, might have had your ardour in some degree abated, by seeing a poet in the decline of life.’

Despite what we may think of Robert Southey’s advice now, it seems clear that Charlotte’s ardour for it or the poet himself never abated, even if, thankfully for us all, the course of her life, and of the life of her fellow Briery Close guest Elizabeth Gaskell, disproved the advice he had given. I hope to see you all next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Wonderful insights, as usual. Thank you soooo much.