The Brontë sisters Charlotte, Emily and Anne were writers of genius. Their lives are fascinating and their works are fascinating, and one of the most fascinating questions we can ask about them is where did that genius come from: was it nature or nurture?

The Brontë siblings are surely unparalleled in literary history: where else are there three siblings all possessed of such great creative skills? In today’s post we look at a remarkable letter written by Charlotte Brontë on this weekend in 1836, and particularly at a section which gives us a remarkable insight into her own creative vision, in every sense of the word.

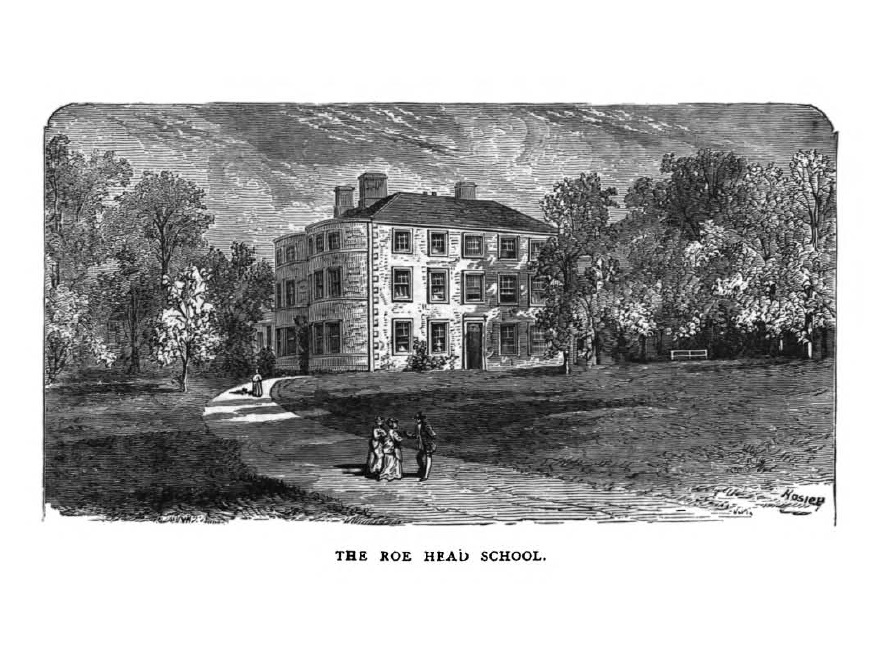

The letter in question was written on October 14th of that year and forms part of what has become known as the Roe Head Journal. This was not a journal as such, but a series of letters written by a 20 year old Charlotte Brontë when she was a teacher at Roe Head school at Mirfield (Anne Brontë’s drawing of the school is at the head of this post).

As this ‘journal’ makes clear, Charlotte was temperamentally very unsuited to be a teacher. Like all the Brontës she was shy and reserved by nature, and never comfortable in the company of others. She was a very generous woman, but she could also be less than tolerant of mistakes in others, and patience was never her strong point. Charlotte was also suffering from severe depressive episodes at this point, exacerbated by the situation she found herself in: she was trapped in a classroom when she longed to be at home in Haworth writing with her siblings. We see all this and more in the Roe Head journal, as it is written with Charlotte’s characteristic frankness. We will start with an extract that sums up Charlotte’s agony at her life as a teacher:

We find Charlotte here driven to a very low ebb by pupils such as Ellen Lister and Miss Marriott, but in her great fatigue she drifts into a vision. This vision is given remarkable clarity in Charlotte’s letter, and we can conjecture that the figure of a lady standing in a hall in a gentleman’s house remained with her, burnt into her memory, until it found its way onto the printed page ten years later in the form of Jane Eyre. Here is Charlotte’s account of what happened next:

For Charlotte Brontë, just as it famously was for Emily Brontë, creativity was a visionary process – these great poems and great novels were somehow within them and at times they would burst forth into their imagination, taking physical form before them, and on auspicious occasions for us all finding their way onto that pages of posterity.

Last week I spoke of bringing you details of the Anne Brontë exhibition currently taking place in Scarborough – I’m waiting to receive more details of the event from its organisers, but I now hope to bring it to you next week. If you’re in Scarborough in the intervening period do go and check it out at the Maritime Museum.

I hope you’ve had a great week, but if you’re feeling low like Charlotte Brontë was then why not take up your pen and do what she did – journal your thoughts in an act of restorative creativity. As the Brontës knew, writing can be a powerful tool for the reader and the writer alike! I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.