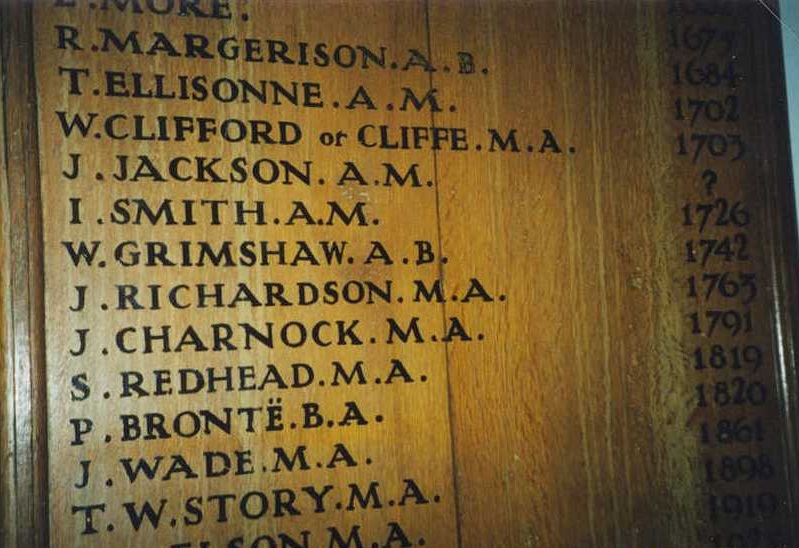

A plaque within St. Michael and All Angels church in Haworth lists the parish priests of the village, and the date that they entered service there. There are some illustrious names on there, including the long serving Reverend James Charnock and the celebrated Reverend William Grimshaw, an important figure in the history and formation of Methodism – famed for his long and passionate sermons that could last all day, he was said sometimes to head to the nearby Black Bull Inn and quite literally whip the inhabitants into his church!

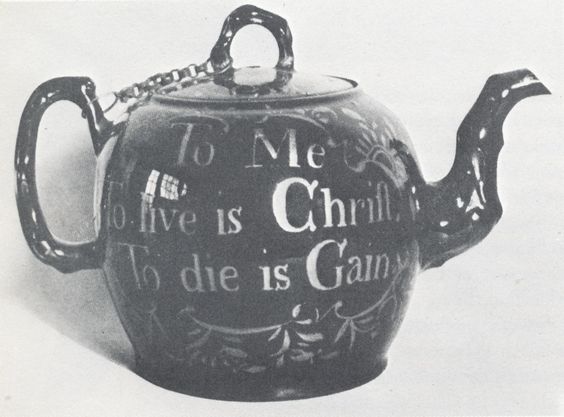

On one occasion Grimshaw fainted during his sermon, but revived enough to tell the parishioners to wait in the church until he returned. He fainted again and was carried to his house, and when he came round his first words were, ‘I have had a glorious vision from the third heaven’, after which he went back to the church and preached until seven in the evening! Robert Southey, the poet laureate perhaps most famous today for his advice to a young Charlotte Brontë to give up writing, wrote a biography of William Grimshaw in which he opined: ‘In his unconverted state this person was certainly insane; and, had he given utterance at that time to the monstrous and horrible imaginations which he afterwards revealed to his spiritual friends, he would deservedly have been sent to Bedlam.’ Nevertheless, Reverend Grimshaw was hugely popular, and crowds would flock to hear him preach so that he sometimes had to deliver his sermons on the moors rather than inside his church. Aunt Branwell was a fan of his, so much so that she had a William Grimshaw teapot bearing his name and his favourite quote: ‘To Me, to live is Christ, to die is Gain.” The teapot is now part of the Brontë Parsonage Museum collection.

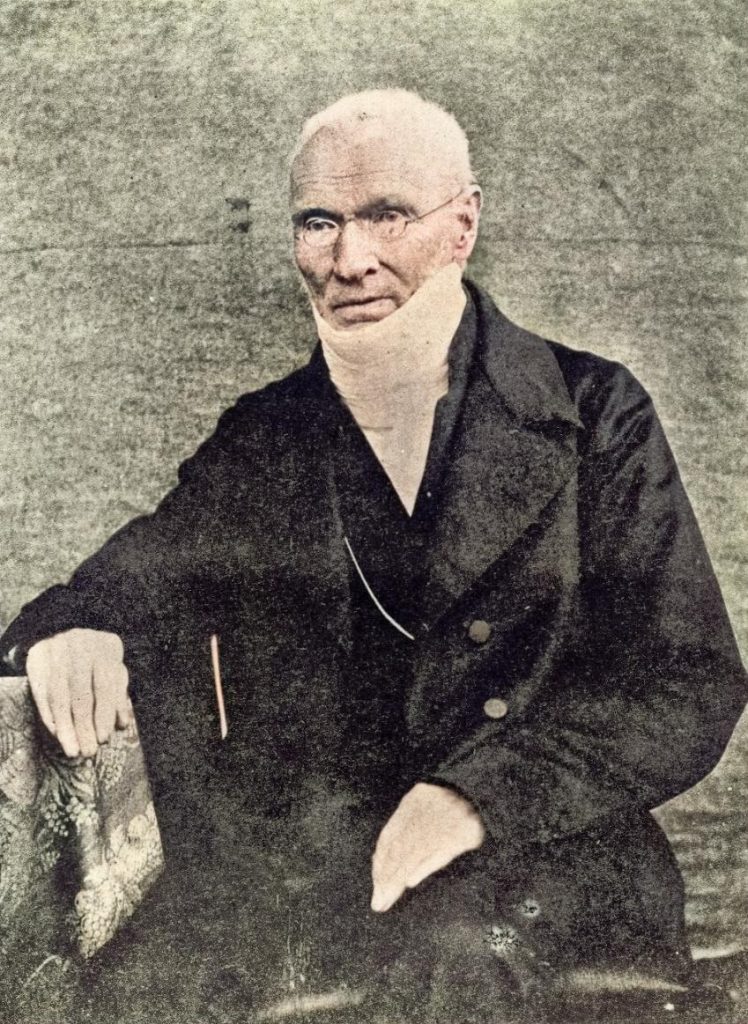

Because of Grimshaw’s celebrity, the parish of Haworth gained a fame too, and to be its rector was a coveted position – even though Church of England politics meant that its rector was not actually a vicar in their own right but subservient to the Vicar of Bradford who appointed Haworth’s curate alongside the parish panel of trustees. This was a delicate balancing act – and led to the delayed introduction of the man whose fame would eclipse that even of Grimshaw. The man who would serve as Haworth’s rector for over forty years, but whose greatest claim to fame was being the father of three daughters he raised in Haworth Parsonage. The man was the Reverend Patrick Brontë of course who served as parish priest from 1820 until 1861. He was the longest serving priest of Haworth, but today we are going to look at its shortest serving priest Reverend Samuel Redhead – Patrick’s direct predecessor.

After the passing of Reverend Charnock in 1819, Patrick Brontë had been approached by the vicar of Bradford to leave his position as curate of Thornton and became the new rector of Haworth. The parishioners of Haworth, or at least their trustees, however, had not been consulted and made their opposition known. This was no slight against Patrick, who had officiated in Haworth on numerous occasions during Reverend Charnock’s decline, but simply an assertion of what they saw as their rights to choose their own priest. When Patrick heard of this opposition he stepped aside, and the vicar of Bradford, Reverend Henry Heap, repeated his earlier mistake and once again announced his intention to unilaterally impose a priest on Haworth. Samuel Redhead was installed as priest, but on this day in 1819 he announced his resignation – his official term as Haworth’s priest which earned him his place on the church plaque had lasted just three weeks.

What happened? Chaos happened, as two fascinating accounts show. We will first turn to the account given by Elizabeth Gaskell in her The Life Of Charlotte Brontë:

‘In conversing on the character of the inhabitants of the West Riding with Dr. Scoresby, who had been for some time Vicar of Bradford, he alluded to certain riotous transactions which had taken place at Haworth on the presentation of the living to Mr. Redhead, and said that there had been so much in the particulars indicative of the character of the people, that he advised me to inquire into them. I have accordingly done so, and, from the lips of some of the survivors among the actors and spectators, I have learnt the means taken to eject the nominee of the Vicar.

The previous incumbent had been the Mr. Charnock whom I have mentioned as next but one in succession to Mr. Grimshaw. He had a long illness which rendered him unable to discharge his duties without assistance, and Mr. Redhead gave him occasional help, to the great satisfaction of the parishioners, and was highly respected by them during Mr. Charnock’s lifetime. But the case was entirely altered when, at Mr. Charnock’s death in 1819, they conceived that the trustees had been unjustly deprived of their rights by the Vicar of Bradford, who appointed Mr. Redhead as perpetual curate.

The first Sunday he officiated, Haworth Church was filled even to the aisles; most of the people wearing the wooden clogs of the district. But while Mr. Redhead was reading the second lesson, the whole congregation, as by one impulse, began to leave the church, making all the noise they could with clattering and clumping of clogs, till, at length, Mr. Redhead and the clerk were the only two left to continue the service. This was bad enough, but the next Sunday the proceedings were far worse. Then, as before, the church was well filled, but the aisles were left clear; not a creature, not an obstacle was in the way. The reason for this was made evident about the same time in the reading of the service as the disturbances had begun the previous week. A man rode into the church upon an ass, with his face turned towards the tail, and as many old hats piled on his head as he could possibly carry. He began urging his beast round the aisles, and the screams, and cries, and laughter of the congregation entirely drowned all sound of Mr. Redhead’s voice, and, I believe, he was obliged to desist.

Hitherto they had not proceeded to anything like personal violence; but on the third Sunday they must have been greatly irritated at seeing Mr. Redhead, determined to brave their will, ride up the village street, accompanied by several gentlemen from Bradford. They put up their horses at the Black Bull – the little inn close upon the churchyard, for the convenience of arvills as well as for other purposes – and went into church. On this the people followed, with a chimney-sweeper, whom they had employed to clean the chimneys of some out-buildings belonging to the church that very morning, and afterward plied with drink till he was in a state of solemn intoxication. They placed him right before the reading-desk, where his blackened face nodded a drunken, stupid assent to all that Mr. Redhead said. At last, either prompted by some mischief-maker, or from some tipsy impulse, he clambered up the pulpit stairs, and attempted to embrace Mr. Redhead. Then the profane fun grew fast and furious. Some of the more riotous, pushed the soot-covered chimney-sweeper against Mr. Redhead, as he tried to escape. They threw both him and his tormentor down on the ground in the churchyard where the soot-bag had been emptied, and, though, at last, Mr. Redhead escaped into the Black Bull, the doors of which were immediately barred, the people raged without, threatening to stone him and his friends. One of my informants is an old man, who was the landlord of the inn at the time, and he stands to it that such was the temper of the irritated mob, that Mr. Redhead was in real danger of his life. This man, however, planned an escape for his unpopular inmates. The Black Bull is near the top of the long, steep Haworth street, and at the bottom, close by the bridge, on the road to Keighley, is a turnpike. Giving directions to his hunted guests to steal out at the back door (through which, probably, many a ne’er-do-weel has escaped from good Mr. Grimshaw’s horsewhip), the landlord and some of the stable-boys rode the horses belonging to the party from Bradford backwards and forwards before his front door, among the fiercely-expectant crowd. Through some opening between the houses, those on the horses saw Mr. Redhead and his friends creeping along behind the street; and then, striking spurs, they dashed quickly down to the turnpike; the obnoxious clergyman and his friends mounted in haste, and had sped some distance before the people found out that their prey had escaped, and came running to the closed turnpike gate.’

Another account is given by an impeccable source – Charles Longley, at the time Bishop of Ripon but later Archbishop of Canterbury:

‘There is an ancient feud between Bradford and Haworth… the people of Haworth can by the trust deed of the living, prevent the person appointed by the vicar [of Bradford] from entering the Parsonage or receiving any of the emoluments, if he does not please them… in the case of Mr. Redhead, the inhabitants exercised their right of resistance and opposition and to such a point did they carry it, that they actually brought a Donkey into the church while Mr. Redhead was officiating and held up its head to stare him in the face – they then laid a plan to crush him to death in the vestry, by pushing a table against him as he was taking off his surplice and hanging it up, foiled in this for some reason or other they then turned out into the Churchyard where Mr. Redhead was going to perform a funeral and were determined to throw him into the grave and bury him alive.’

Given the circumstances, it’s little wonder that Reverend Redhead declined to return to Haworth for a fourth week! Realising he was at an impasse the vicar of Bradford Reverend Heap finally sat down with the elders of Haworth and in early 1820, just weeks after the birth of his youngest daughter Anne, a new parish priest was announced that was this time approved by both sides: Reverend Patrick Brontë. His move changed the fortunes of Haworth forever, so that it is now a centre of worldwide fame and literary tourism.

What became of Samuel Redhead? It may seem incredible, but he became a regular understudy to Patrick Brontë and officiated in Haworth many times, but on those occasions he was welcomed with friendship and not a little laughter by the parishioners – and donkeys were kept well away from his pulpit. Reverend Redhead, unlike Patrick, came from a wealthy family and he was one of the people who came to Patrick’s aid after the death of his wife Maria – helping Patrick pay off the debts and medical bills he incurred during his wife’s long illness.

Haworth was a remarkable place then and now, but visitors to this steep and beautiful moorside parish today are assured of a rather warmer welcome than Samuel Redhead first received! I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post – all are welcome, even donkeys and chimney sweeps.