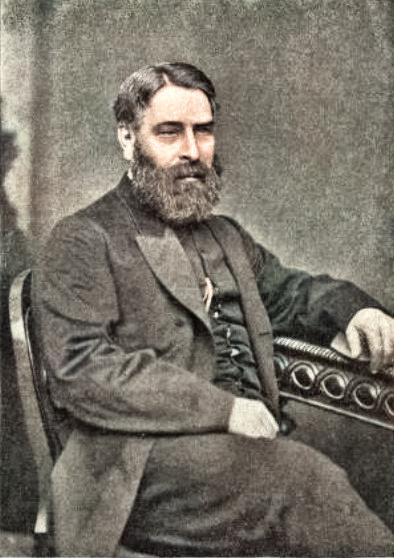

This weekend marks the anniversary of what could in effect be said to be the last chapter of the Brontë story, yet the year in which it occurred is much nearer than you might imagine: 1906. On 2nd December of that year, Arthur Bell Nicholls died in Banagher, County Offally. He was the widower of Charlotte Brontë, and Arthur’s death marked the last passing of one who was central to the Brontë legend. He remarried faithful to the memory of his wife long after her passing, and his Hill House home became almost a shrine to Charlotte and her family, as we shall see in today’s post.

After Charlotte’s untimely and tragic death in 1855, Arthur returned to his Irish homeland – to Banagher, the town in which he had been raised by his uncle Dr. Alan Bell alongside his younger cousin Mary Anna. Arthur and Mary, 11 years his junior, were very close, and Charlotte sang her praises after meeting her during her 1854 honeymoon:

‘The other cousin [Mary Anna] was a pretty lady-like girl with gentle English manners. They accompanied us last Friday down to Banagher – his Aunt’s – Mrs. Bell’s residence, where we are now… In this house Mr. Nicholls was brought up by his uncle Dr. Bell… The male members of this family – such as I have seen seem thoroughly educated gentlemen. Mrs. Bell is like an English or Scottish matron quiet, kind and well-bred – it seems she was brought up in London. Both her daughters are strikingly pretty in appearance – and their manners are very amiable and pleasing. I must say I like my new relations.’

After his return to Ireland Arthur found solace in the company of Mary, and in 1864 they married. It seems to me that this was a marriage of convenience; they had been brought up, in effect, as brother and sister, and Arthur remained devoted to Charlotte throughout his life, seemingly without a hint of jealousy from his second wife. We know this from a number of accounts from people who visited Arthur in Banagher, including from Clement King Shorter, the Brontë biographer who became President of the Brontë Society, but was in fact a con man who defrauded Ellen Nussey in particular out of numerous Bronte treasures.

I will give an account now, however, of one who knew Arthur and his second wife Mary well – their niece Harriett Bell. In 1927 she gave the following account to Cornhill Magazine:

‘My uncle had very definite and rigid views. I remember as a child hearing a deep groan of disapproval issuing from the Hill House pew when something that was said by the preacher (not my father!) excited his displeasure. Though he retired from the church on account of throat trouble, he was a healthy man. But in his youth a doctor had told him that he had a weak heart, and for the rest of his long life his wife used to detect him every now and then surreptitiously feeling his pulse, much to her quiet amusement!

The Hill House was full of Brontë relics. The drawing-room walls were hung with their wonderful pencil drawings. Old Mr Brontë’s rifle leaned against a corner in the dining-room.

Upstairs was the chair at which Charlotte always kneeled to pray, as did her husband after her death. In a drawer, carefully treasured by my aunt, were the little muslin wedding-dress, small one-buttoned gloves, and the sandalled shoes, just as they had been placed together by Charlotte herself many years before.

The store-room was fragrant with the smell of sponge-cake, made from the recipe of Martha, the maid from Haworth Vicarage, who accompanied Mr Nicholls to Ireland after the death of old Mr Brontë.

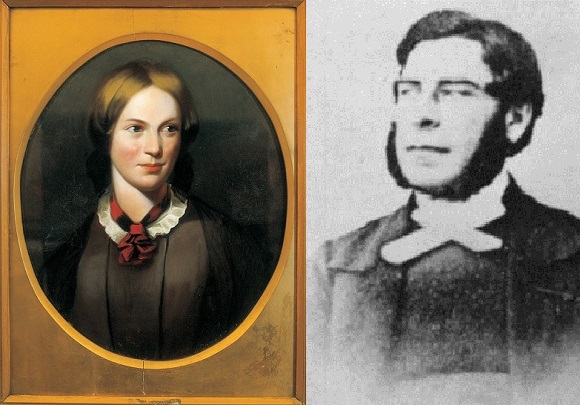

The picture of Charlotte Brontë which was left by my uncle to the National Portrait Gallery used to hang in the centre of the drawing room wall, with a table underneath. My aunt’s sofa was beyond the table. Once the portrait fell from the wall, skipped the table, and in some mysterious way fell on Aunt Mary. Luckily, neither she nor the picture suffered, but she thought it a curious incident.

After my uncle died she had his coffin brought down and placed beneath the picture. A rough sketch by Branwell Brontë of his sisters was stowed away on the top of an old cupboard. My aunt attached no value to it, as she said it was ‘so bad of the girls’, and was reluctant to its being sent to London after her husband’s death, but it now also hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.’

A fascinating first-hand account that reveals why Arthur quit the church, and what happened to what is now one of the most famous literary portraits of them all: the pillar portrait of the Bronte sisters made by their brother Branwell.

Another relative of Arthur, his great-niece Marjorie Gallop gave the following account of Arthur and his passing:

‘‘With generous loyalty, Mary Nicholls made every room in the house a Brontë shrine. The drawing room was hung with the sisters’ drawings, Mr. Brontë’s gun leaned up against the dining room wall, and Charlotte’s portrait overlooked the sofa on which Mary used to rest. One day it broke away from the wall, missed a table which stood below it, and fell on to Mary. Neither the portrait nor Mary was harmed. When Arthur died, Mary had his coffin placed beneath the portrait until it was carried from the house.’

It took a long time for Charlotte Brontë to find the love of her life: Arthur Bell Nicholls. They were married for far too little a time, a cruel curtailing of the joy Charlotte had yearned for all her life. But it was thanks to Arthur that she knew this happiness. She loved Arthur briefly but deeply, but Arthur’s love for her was going strong into the twentieth century. Let us remember him today. I am thrilled to say that Arthur and Charlotte are being remembered in Banagher. Hill House is now the stunning Charlotte’s Way guesthouse, and yesterday it held the inaugural meeting of a new Irish Brontë Society dedicated to the memory of Charlotte and Arthur. I wish it all the luck in the world, and I wish you to join me here next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.