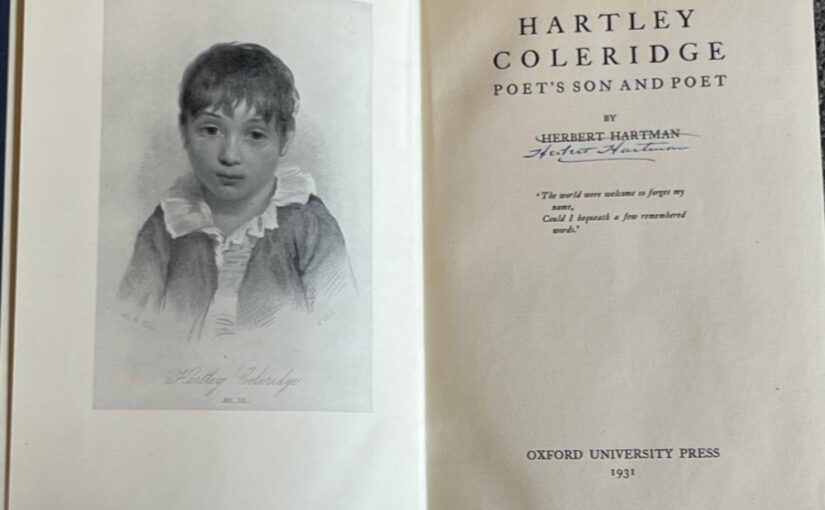

In previous posts we looked at how a young Charlotte Brontë sent her poetry to poet laureate Robert Southey, who gave it short shrift and insisted that literature could not and should not be a woman’s work. At the same time, Charlotte was sending samples of her prose to another person associated with the romantic poetry movement: Hartley Coleridge. In today’s post we’ll look at a letter she sent to him on this day 1840, and what it tells us about her dreams of writing at the time.

Hartley Coleridge was a son of famed poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, but that proved to be an albatross around his neck. Whilst he himself wrote poetry, he could never match his father’s fame or talents, although he did inherit a taste for alcohol and opiates – it was this intemperance that led to Hartley being dismissed from a position as a fellow of Oxford University. Nevertheless, William Wordsworth, a close friend of his father, took a keen, avuncular interest in Hartley, and the Brontës were great fans of his work. In later years, Branwell shared his own poetry with Hartley and received encouraged from him, but it seems that Charlotte’s early prose received less encouragement, as we can see in the letter sent in return by Charlotte Brontë 183 years ago today:

“Sir, I was almost as much pleased to get your letter as if it had been one from Professor Wilson containing a passport of admission to Blackwood — You do not certainly flatter me very much nor suggest very brilliant hopes to my imagination — but on the whole I can perceive that you write like an honest man and a gentleman — and I am very much obliged to you both for the candour and civility of your reply. It seems then Messrs Percy and West are not gentlemen likely to make an impression upon the heart of any Editor in Christendom? wellI commit them to oblivion with several tears and much affliction but I hope I Can get over it.

Your calculation that the affair might have extended to three Vols is very moderate — I felt myself actuated by the pith and perseverance of a Richardson and could have held the distaff and spun day and night till I had lengthened the thread to thrice that extent — but you, like a most pitiless Atropos, have cut it short in its very commencement — I do not think you would have hesitated to do the same to the immortal Sir Charles Grandison if Samuel Richardson Esqr. had sent you the first letters of Miss Harriet Byron—and Miss Lucy Selby for inspection — very good letters they are Sir, Miss Harriet sings her own praises as sweetly as a dying swan — and her friends all join in the chorus, like a Company of wild asses of the desert.

It is very edifying and profitable to create a world out of one’s own brain and people it with inhabitants who are like so many Melchisedecs — ‘‘Without father, without mother, without descent, having neither beginning of days, nor end of life’’. By conversing daily with such beings and accustoming your eyes to their glaring attire and fantastic features — you acquire a tone of mind admirably calculated to enable you to cut a respectable figure in practical life — If you have ever been accustomed to such society Sir you will be aware how distinctly and vividly their forms and features fix themselves on the retina of that ‘‘inward eye’’ which is said to be ‘‘the bliss of solitude’’. Some of them are so ugly — you can liken them to nothing but the grotesque things carved by a besotted pagan for his temple — and some of them so preternaturally beautiful that their aspect startles you as much as Pygmalion’s Statue must have startled him — when life began to animate its chiselled features and kindle up its blind, marble eyes. I am sorry Sir I did not exist forty or fifty years ago when the Lady’s magazine was flourishing like a green bay tree — in that case I make no doubt my aspirations after literary fame would have met with due encouragement — Messrs Percy and West should have stepped forward like heroes upon a stage worthy of their pretensions and I would have contested the palm with the Authors of Derwent Priory — of the Abbey and of Ethelinda. — You see Sir I have read the Lady’s Magazine and know something of its contents — though I am not quite certain of the correctness of the titles I have quoted for it is long, very long since I perused the antiquated print in which those tales were given forth — I read them before I knew how to criticize or object — they were old books belonging to my mother or my Aunt; they had crossed the Sea, had suffered ship-wreck and were discoloured with brine— I read them as a treat on holiday afternoons or by stealth when I should have been minding my lessons — I shall never see anything which will interest me so much again — One black day my father burnt them because they contained foolish love-stories. With all my heart I wish I had been born in time to contribute to the Lady’s magazine.The idea of applying to a regular Novel-publisher — and seeing all my characters at length in three Vols, is very tempting — but I think on the whole I had better lock up this precious manuscript — wait till I get sense to produce something which shall at least aim at an object of some kind and meantime bind myself apprentice to a chemist and druggist if I am a young gentleman or to a Milliner and Dressmaker if I am a young lady.

You say a few words about my politics intimating that you suppose me to be a high Tory belonging to that party which claims for its head his Serene highness the Prince of the Powers of the Air. I would have proved that to perfection if I had gone on with the tale — I would have made old Thornton a just representative of all the senseless, frigid prejudices of conservatism — I think I would have introduced a Puseyite too and polished-off the High Church with the best of Warren’s jet blacking. I am pleased that you cannot quite decide whether I belong to the soft or the hard sex — and though at first I had no intention of being enigmatical on the subject — yet as I accidentally omitted to give the clue at first, I will venture purposely to withhold it now — as to my handwriting, or the ladylike tricks you mention in my style and imagery — you must not draw any conclusion from those — Several young gentlemen curl their hair and wear corsets — Richardson and Rousseau — often write exactly like old women — and Bulwer and Cooper and Dickens and Warren like boarding-school misses.

Seriously Sir, I am very much obliged to you for your kind and candid letter — and on the whole I wonder you took the trouble to read and notice the demi-semi novelette of an anonymous scribe who had not even the manners to tell you whether he was a man or woman or whether his common-place ‘‘C T’’ meant Charles Tims or Charlotte Tomkins.You ask how I came to hear of you — or of your place of residence or to think of applying to you for advice — These things are all a mystery Sir — It is very pleasant to have something in one’s power — and to be able to give a Lord Burleigh shake of the head and to look wise and important even in a letter. I did not suspect you were your Father.”

It is clear to see that Hartley was not over-enamoured with Charlotte’s early work, but he must have seen some promise as he advised her to write longer works – the fashion at the time, especially as most book sales were sold by volume to circulating libraries – meaning a three volume book made three times as much money. Also fascinating is Charlotte’s reference to Lady’s Magazine.

This clearly was a great favourite of her mother Maria, for it was her possessions that were shipwrecked in 1812 en route from Cornwall to a new home in Yorkshire. It was these magazines, then, that Charlotte devoured in her teens and in her youth, and which eventually led to the monumental genius of her novels.

Charlotte Brontë was not only a brilliant and fascinating novelist, she was also a brilliant and fascinating letter writer, and every epistle that dripped from her quill gives us a fascinating insight into her life, family and times. I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.