Thanks to all who came to see me discuss Anne Brontë at the Bradford Literature Festival last Sunday – it was great to see how many Anne fans there are out there, and it was lovely, as always, to hear people say how much they enjoy this blog! It’s a real labour of love for me, so I’m glad that people enjoy reading it just as much as I enjoy writing it.

I apologise in advance to some of you for the subject matter of today’s post. I’m a football fan and Euro fever has me in its grasp as I look forward to the big final tonight! I promise there will be no 4-4-2 or VAR discussions to follow, but we are going to look at three lions on a shirt, er I mean three lions in Brontë writing.

Jane Eyre

“No – no – Jane; you must not go. No – I have touched you, heard you, felt the comfort of your presence – the sweetness of your consolation: I cannot give up these joys. I have little left in myself – I must have you. The world may laugh – may call me absurd, selfish – but it does not signify. My very soul demands you: it will be satisfied, or it will take deadly vengeance on its frame.”

“Well, sir, I will stay with you: I have said so.”

“Yes – but you understand one thing by staying with me; and I understand another. You, perhaps, could make up your mind to be about my hand and chair – to wait on me as a kind little nurse (for you have an affectionate heart and a generous spirit, which prompt you to make sacrifices for those you pity), and that ought to suffice for me no doubt. I suppose I should now entertain none but fatherly feelings for you: do you think so? Come – tell me.”

“I will think what you like, sir: I am content to be only your nurse, if you think it better.”

“But you cannot always be my nurse, Janet: you are young – you must marry one day.”

“I don’t care about being married.”

“You should care, Janet: if I were what I once was, I would try to make you care – but – a sightless block!”

He relapsed again into gloom. I, on the contrary, became more cheerful, and took fresh courage: these last words gave me an insight as to where the difficulty lay; and as it was no difficulty with me, I felt quite relieved from my previous embarrassment. I resumed a livelier vein of conversation.

“It is time some one undertook to rehumanise you,” said I, parting his thick and long uncut locks; “for I see you are being metamorphosed into a lion, or something of that sort. You have a ‘faux air’ of Nebuchadnezzar in the fields about you, that is certain: your hair reminds me of eagles’ feathers; whether your nails are grown like birds’ claws or not, I have not yet noticed.”

“On this arm, I have neither hand nor nails,” he said, drawing the mutilated limb from his breast, and showing it to me. “It is a mere stump – a ghastly sight! Don’t you think so, Jane?”

“It is a pity to see it; and a pity to see your eyes – and the scar of fire on your forehead: and the worst of it is, one is in danger of loving you too well for all this; and making too much of you.”

“I thought you would be revolted, Jane, when you saw my arm, and my cicatrised visage.”

“Did you? Don’t tell me so – lest I should say something disparaging to your judgment. Now, let me leave you an instant, to make a better fire, and have the hearth swept up.

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

Near the top of this hill, about two miles from Linden-Car, stood Wildfell Hall, a superannuated mansion of the Elizabethan era, built of dark grey stone, venerable and picturesque to look at, but doubtless, cold and gloomy enough to inhabit, with its thick stone mullions and little latticed panes, its time-eaten air-holes, and its too lonely, too unsheltered situation, – only shielded from the war of wind and weather by a group of Scotch firs, themselves half blighted with storms, and looking as stern and gloomy as the Hall itself. Behind it lay a few desolate fields, and then the brown heath-clad summit of the hill; before it (enclosed by stone walls, and entered by an iron gate, with large balls of grey granite – similar to those which decorated the roof and gables – surmounting the gate-posts) was a garden, – once stocked with such hard plants and flowers as could best brook the soil and climate, and such trees and shrubs as could best endure the gardener’s torturing shears, and most readily assume the shapes he chose to give them, – now, having been left so many years untilled and untrimmed, abandoned to the weeds and the grass, to the frost and the wind, the rain and the drought, it presented a very singular appearance indeed. The close green walls of privet, that had bordered the principal walk, were two-thirds withered away, and the rest grown beyond all reasonable bounds; the old boxwood swan, that sat beside the scraper, had lost its neck and half its body: the castellated towers of laurel in the middle of the garden, the gigantic warrior that stood on one side of the gateway, and the lion that guarded the other, were sprouted into such fantastic shapes as resembled nothing either in heaven or earth, or in the waters under the earth; but, to my young imagination, they presented all of them a goblinish appearance, that harmonised well with the ghostly legions and dark traditions our old nurse had told us respecting the haunted hall and its departed occupants.

I had succeeded in killing a hawk and two crows when I came within sight of the mansion; and then, relinquishing further depredations, I sauntered on, to have a look at the old place, and see what changes had been wrought in it by its new inhabitant. I did not like to go quite to the front and stare in at the gate; but I paused beside the garden wall, and looked, and saw no change – except in one wing, where the broken windows and dilapidated roof had evidently been repaired, and where a thin wreath of smoke was curling up from the stack of chimneys.

While I thus stood, leaning on my gun, and looking up at the dark gables, sunk in an idle reverie, weaving a tissue of wayward fancies, in which old associations and the fair young hermit, now within those walls, bore a nearly equal part, I heard a slight rustling and scrambling just within the garden; and, glancing in the direction whence the sound proceeded, I beheld a tiny hand elevated above the wall: it clung to the topmost stone, and then another little hand was raised to take a firmer hold, and then appeared a small white forehead, surmounted with wreaths of light brown hair, with a pair of deep blue eyes beneath, and the upper portion of a diminutive ivory nose.

The eyes did not notice me, but sparkled with glee on beholding Sancho, my beautiful black and white setter, that was coursing about the field with its muzzle to the ground. The little creature raised its face and called aloud to the dog. The good-natured animal paused, looked up, and wagged his tail, but made no further advances. The child (a little boy, apparently about five years old) scrambled up to the top of the wall, and called again and again; but finding this of no avail, apparently made up his mind, like Mahomet, to go to the mountain, since the mountain would not come to him, and attempted to get over; but a crabbed old cherry-tree, that grew hard by, caught him by the frock in one of its crooked scraggy arms that stretched over the wall. In attempting to disengage himself his foot slipped, and down he tumbled – but not to the earth; – the tree still kept him suspended. There was a silent struggle, and then a piercing shriek; – but, in an instant, I had dropped my gun on the grass, and caught the little fellow in my arms.

I wiped his eyes with his frock, told him he was all right and called Sancho to pacify him. He was just putting a little hand on the dog’s neck and beginning to smile through his tears, when I heard behind me a click of the iron gate, and a rustle of female garments, and lo! Mrs. Graham darted upon me – her neck uncovered, her black locks streaming in the wind.

“Give me the child!” she said, in a voice scarce louder than a whisper, but with a tone of startling vehemence, and, seizing the boy, she snatched him from me, as if some dire contamination were in my touch, and then stood with one hand firmly clasping his, the other on his shoulder, fixing upon me her large, luminous dark eyes – pale, breathless, quivering with agitation.

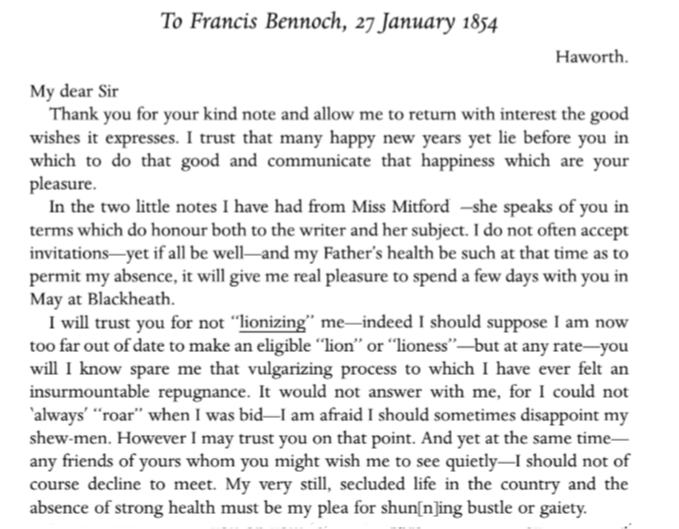

Charlotte Brontë, Letter to Francis Bennoch

So there we have three lions in the Brontë writing. In one we see a disfigured Rochester find hope, then love, with Jane Eyre; in the next we see Gilbert meeting Helen, the eponymous tenant of Wildfell Hall, for the first time, and get a first clue as to her story. Finally, we see the ever humble Charlotte say that, at 37, she is too old for praise – too old to be a lion.

It (a national football trophy) could be coming home for the mens’ team tonight for the first time in 58 years, but let’s not forget that it came home for the lionesses just two years ago when they won Euro 22 for England’s women. Ellen Nussey, loyal friend of the Brontës, called herself a lioness in her very final interview in 1897:

In connection with her correspondence with Charlotte, Miss Nussey said she had often been badly treated, and I quite agreed with her when she informed me of the circumstances. This led me to tell her I had heard something of the kind before, and that I had felt diffident about seeking an interview, but that at last I had yielded, the suggestion being that I should ‘beard the lioness in her den.’ She laughed heartily, and exclaimed, ‘That’s exactly what I am, a lioness. I have to be, because of the way I have been treated.’ To me she was all kindness, and the interview throughout seemed to be mutually satisfactory. We parted, but she called me again to the house door, and then with a nervous air said, ‘Remember! All who have anything to do with the Brontës have had great trouble.’

I promise there will be no football next week and lots of Brontës, but tonight, whatever our nationality and whatever we think of sport, let’s get behind Gareth Southgate and the gang. After all, he lives in Swinsty Hall in Yorkshire just 20 miles from Haworth – which surely makes him an honourary Brontë fan for one night. Whatever the result for England against Spain I hope to see you next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Hi Nick, Glad all went well in Bradford. If I lived nearer, I would have loved to come along. Such an interesting letter from Charlotte to Francis Bennoch (I’d love to know some more about him).

I’m not a football fan as such, but watched the match last night and the better team certainly won (I always thought the aim of football was to take shots at goal, not to simply pass the ball between your team members, but what do I know?).