It’s certainly been a busy few days, but one of the most joyous and moving elements of it has been listening to the new album ‘ The Bluebell’, by Charlie Rauh. It takes some of the greatest poems by Anne and Emily Brontë and sets them to sublime guitar music. I’ll be reviewing it fully in a special post on Wednesday, but for now let’s take a look at a place I visited once more yesterday, Hathersage in words and pictures – you may know it better as Morton in Jane Eyre.

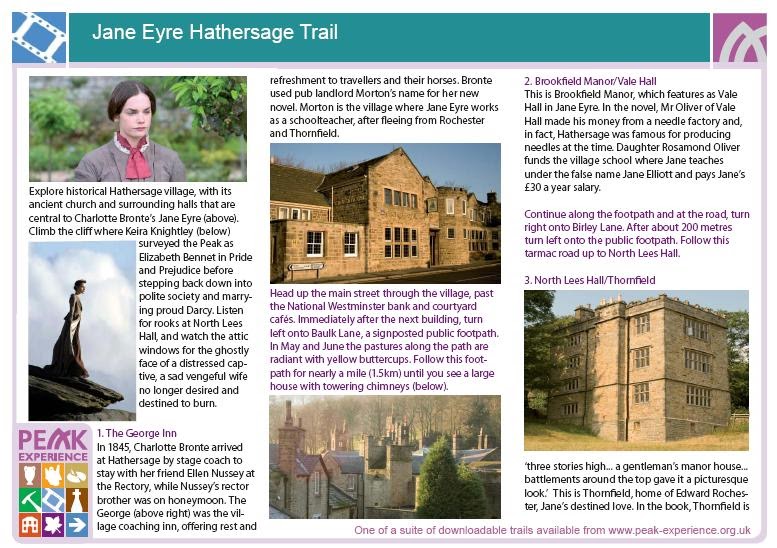

Hathersage is a picturesque village in the Derbyshire Peak District, and like just about everywhere associated with the Brontës it’s rather hilly and a test for the knees. I say associated with the Brontës because Charlotte Brontë visited here in the summer of 1845, spending three weeks with her great friend Ellen Nussey. These weeks were happy but fleeting but their influence has marked English literature for ever, as we shall see when we examine some of Hathersage’s attractions in words and in actuality.

Hathersage Moor

Hathersage Moor is at the northern portion of the Peak District, around ten miles south of South Yorkshire’s largest city Sheffield. Indeed Charlotte caught the train to Sheffield, before taking a coach to Hathersage itself (although it now has its own train station). En route she passed through stunning yet bleak moorland, which must have reminded her of the similar vistas around Haworth. If anything the Peak District moors are bleaker, wilder and more powerful, and it is here that a distraught Jane finds herself after leaving Thornfield Hall and the would-be bigamist Rochester:

‘From the well-known names of these towns I learn in what county I have lighted; a north-midland shire, dusk with moorland, ridged with mountain: this I see. There are great moors behind and on each hand of me; there are waves of mountains far beyond that deep valley at my feet. The population here must be thin, and I see no passengers on these roads: they stretch out east, west, north, and south – white, broad, lonely; they are all cut in the moor, and the heather grows deep and wild to their very verge. Yet a chance traveller might pass by; and I wish no eye to see me now: strangers would wonder what I am doing, lingering here at the sign-post, evidently objectless and lost. I might be questioned: I could give no answer but what would sound incredible and excite suspicion. Not a tie holds me to human society at this moment – not a charm or hope calls me where my fellow-creatures are – none that saw me would have a kind thought or a good wish for me. I have no relative but the universal mother, Nature: I will seek her breast and ask repose. I struck straight into the heath; I held on to a hollow I saw deeply furrowing the brown moorside; I waded knee-deep in its dark growth; I turned with its turnings, and finding a moss-blackened granite crag in a hidden angle, I sat down under it. High banks of moor were about me; the crag protected my head: the sky was over that.’

The George Hotel

One of the first thing that visitors to Hathersage often encounter, now and then, is the George Hotel. Now it’s a rather salubrious location to rest one’s head, and they also serve a fabulous afternoon tea. In 1845 it was the coaching stop for the village, and so it was here that Charlotte alighted. In Jane Eyre Charlotte transports the George Inn (as she calls it) from Hathersage (Morton) to Millcote as her protagonist prepares to return to Thornfield Hall. Portraits of George III still hold a position of prominence in the hotel:

‘A new chapter in a novel is something like a new scene in a play; and when I draw up the curtain this time, reader, you must fancy you see a room in the George Inn at Millcote, with such large figured papering on the walls as inn rooms have; such a carpet, such furniture, such ornaments on the mantelpiece, such prints, including a portrait of George the Third, and another of the Prince of Wales, and a representation of the death of Wolfe. All this is visible to you by the light of an oil lamp hanging from the ceiling, and by that of an excellent fire, near which I sit in my cloak and bonnet; my muff and umbrella lie on the table, and I am warming away the numbness and chill contracted by sixteen hours’ exposure to the rawness of an October day: I left Lowton at four o’clock a.m., and the Millcote town clock is now just striking eight.’

Hathersage Vicarage

The reason for Charlotte’s visit to Hathersage was that Ellen Nussey’s brother had been made vicar of the parish. Whilst Charlotte was there, Henry was on honeymoon with his new bride Emily Prescott (he had previously had a proposal rejected by Charlotte of course). Charlotte and Ellen were overseeing some renovations that Henry had ordered, and the beautiful parsonage building they stayed in was recreated as the home of the Rivers family in Morton:

‘I could not bear to return to the sordid village, where, besides, no prospect of aid was visible. I should have longed rather to deviate to a wood I saw not far off, which appeared in its thick shade to offer inviting shelter; but I was so sick, so weak, so gnawed with nature’s cravings, instinct kept me roaming round abodes where there was a chance of food. Solitude would be no solitude—rest no rest—while the vulture, hunger, thus sank beak and talons in my side.

I drew near houses; I left them, and came back again, and again I wandered away: always repelled by the consciousness of having no claim to ask—no right to expect interest in my isolated lot. Meantime, the afternoon advanced, while I thus wandered about like a lost and starving dog. In crossing a field, I saw the church spire before me: I hastened towards it. Near the churchyard, and in the middle of a garden, stood a well-built though small house, which I had no doubt was the parsonage. I remembered that strangers who arrive at a place where they have no friends, and who want employment, sometimes apply to the clergyman for introduction and aid. It is the clergyman’s function to help—at least with advice—those who wished to help themselves. I seemed to have something like a right to seek counsel here. Renewing then my courage, and gathering my feeble remains of strength, I pushed on. I reached the house, and knocked at the kitchen-door. An old woman opened: I asked was this the parsonage?’

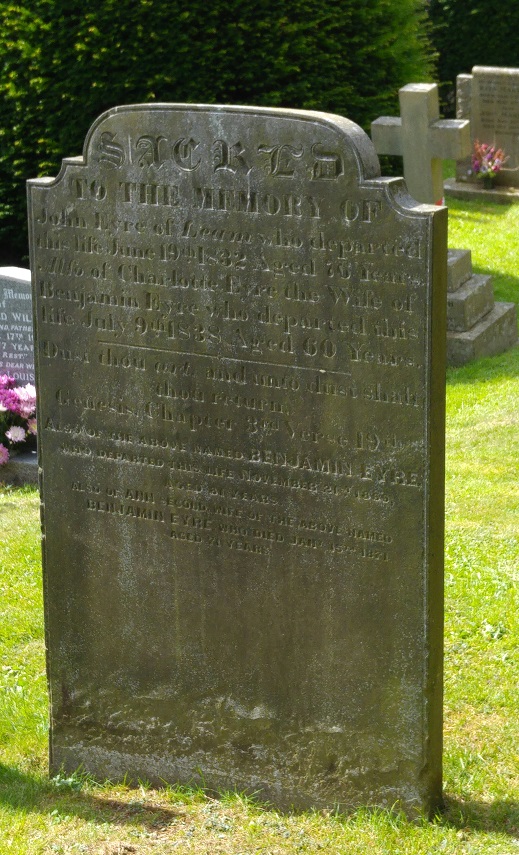

Eyre Family Graves

As described in Jane Eyre, the parsonage with its lovely garden is in the shadow of the spired church of St. Michael and All Angels, and in the graveyard are a number of graves for members of the leading family of the area: the Eyres. Other common names in the churchyard include Higginbottom and Gulliver, so the nation’s favourite heroine could have had a very different name.

North Lees Hall

Charlotte not only saw the Eyre family graves in 1845, she also met the Eyre family themselves at their family seat of North Lees Hall, just over a mile to the north of Hathersage. It’s castellated ramparts are very reminiscent of a famous literary building – Thornfield Hall.

Charlotte was obviously greatly impressed by Hathersage, for its influence upon Jane Eyre cannot be overstated. If you get the opportunity I thoroughly recommend that you visit it and follow in the footsteps of Charlotte and Ellen. In the meantime, stay safe and happy and join me next Sunday for a new Brontë blog post, as well as on Wednesday to hear more about the brilliant album ‘The Bluebell’ by Charlie Rauh.

Just watched the 2011 version of Jane Eyre on BBC One. A timely blog about the area and possible Thornfield Hall.